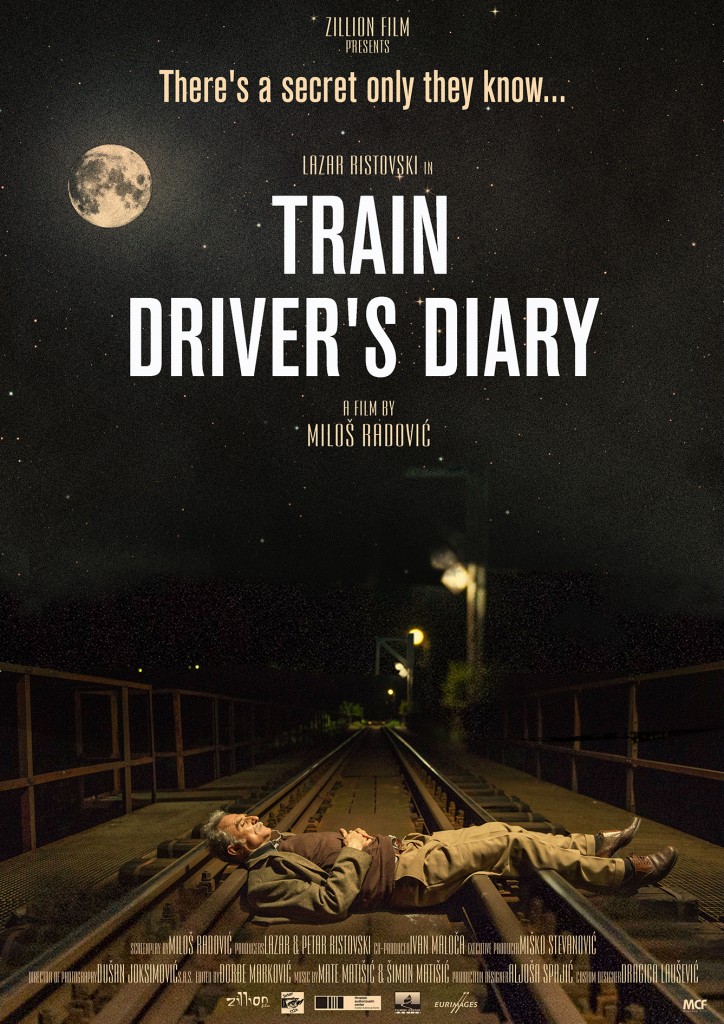

Film “Train Driver’s Diary”, by director Miloš Radović had its world premiere at the International Film Festival in Moscow.

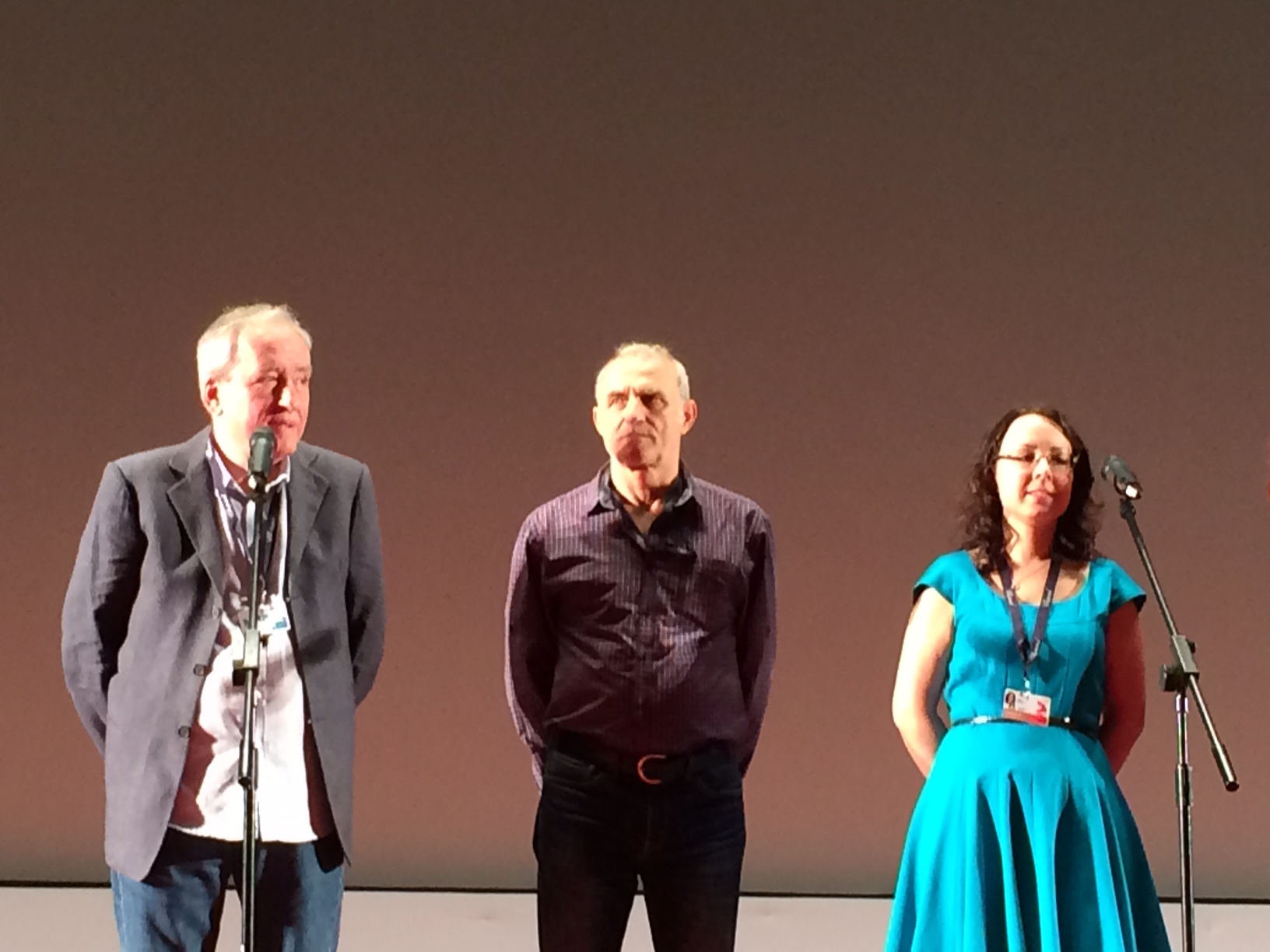

Premiere was attended by director Miloš Radović and actor and producer Lazar Ristovski, who conveyed impressions from the premiere: “After the screening the audience stood up and a round of applause and shouts of “bravo”, and greeted us as artists.”

In addition to the excellent reception came praise the famous film critic Igor Saveljev, who did not hide his delight. “When you design a good concept, has done half the job. Courage is another necessary component” wrote Savelyev.

The film is a comedy-melodrama of innocent murderers and their lives.

Read the full Savelyev’s review:

Devising a proper concept means half the job is done. Audacity is another half. It took certain courage from Miloš Radović to concoct death in all its possible shapes and forms without turning his film into a rampaging black comedy. Or, in spite of the fact it’s ultimately a comedy, to make the audience feel deeply sorry for some characters, although not those who, almost like in Charlie Chaplin films, stupidly end up under a train. “Train Driver’s Diary” is conceptual in the sense that there are certain laws operating in its world which presume death under a train is anything but a tragedy. But I suppose the authors didn’t have to work too hard to make up this concept. It was on the surface, all they had to do was develop the idea further and add a pinch of grotesque. It is almost weird no one had done that before.

The most curious element of the movie is the odd combination of routine railroad regulations and such an extraordinary thing as death. After all, the introduction is not a fruit of the screenwriter’s imagination: statistics knows for certain how many people a train driver will kill during their career (in Russia, 8 to 10 on average). The line between “might” and “should” is indeed very fine. Radović merely shifts the focus from the former to the latter, much like his characters shift gear in the cab, braking more in accordance with the rule than in an attempt to prevent the inevitable. Moreover, real laws from this side of the screen do allocate to the driver a certain number of days off after such an unfortunate incident. Just a bit of film magic can turn this unfortunate incident into a fortunate occasion. The Todorović clan, four generations of which have been driving locomotives, industriously and with a certain pride keep count and occasionally visit the victims’ graves – not their victims, mind, rather the victims of some higher justice whose tools the Todorovićs and thir colleagues think themselves to be. There is some classic element to it, especially to this unusual perception of death, as classic art didn’t share the fear and reluctance we feel towards it nowadays. The characters of “Train Driver’s Diary” live almost like one big family in written-off carriages; their wives and kids sometimes get killed by a train driven by one of their colleagues. But young Simo only feels frightened at first. They don’t mind lying on the tracks themselves for some tactic reason, which again gives out the classic belief that death is not the end. The appearance of grey-haired Ilija Todorović’s long since deceased wife who doesn’t seem a day older, might serve as an indirect proof of it. On the other hand, everyone believes old Ilija has simply gone nuts. Without departing even for a second from the logic of the real life, Miloš Radović miraculously combines it with huge doses of grotesque, which makes watching one Todorović growing old and another maturing incredibly funny.

While coming of age is more or less clear (with first sex as an initiation ritual naturally turning into first incident on the railroad), growing old obtains one more level of meaning. It has nothing to do with comic situations or the theme of implacable fate that can’t be stopped. It is an accurate study of callousness that grows in a person with age if they haven’t experienced enough love. However, Radović chooses to end this storyline be melting the ice in Ilija’s heart as he at last plucks up courage to hold his son and tell him something encouraging. After all, the film must contain something the audience is used to. And classic finale where everyone dies might’ve betn a bit too much for them.

Igor Savelyev