By Daniel Einhäuser, 04. January 2021

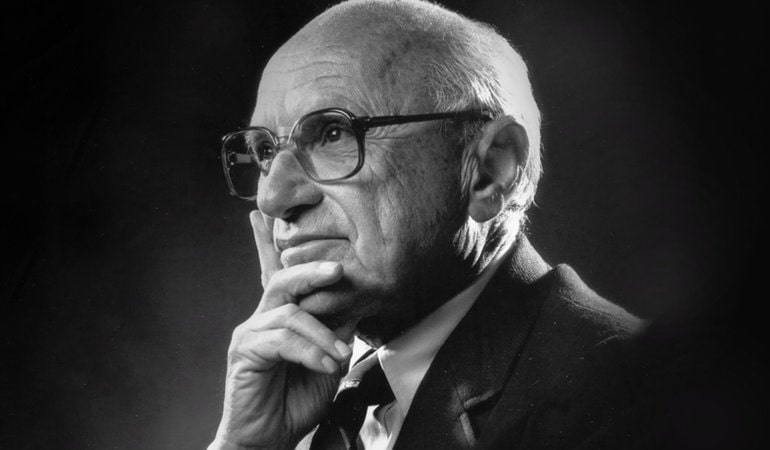

50 years ago, in September 1970, Milton Friedman published his famous article “A Friedman Doctrine – The Social Responsibility Of Business Is to Increase Its Profits” in The New York Times.

It was a controversial message that the professor at the University of Chicago sent:

Companies have no social responsibility but only a responsibility to their shareholders, which is to make as much profit as possible. Exercising social responsibility would reduce profits and therefore would not be in line with shareholders’ interest of maximizing returns. Hence, socially responsible behaviour is only expected from individuals and Governments.

The fundamental idea, that activities of corporate executives need to be synchronized with the interests of their company’s shareholders contributed to the shareholder value concept, which basically aims at increasing the financial returns for shareholders. Consequently, management was incentivized accordingly, which increased executive remuneration, made share buybacks a popular tool and generally sparked a management behaviour that at times was driven by short-term action rather than a long-term strategy.

But here we are: half a century after Friedman’s article and times have changed. The Generation Z is influencing consumption patterns and a young girl from Sweden laid the foundation to the global movement “Fridays for Future” which had a significant impact on the political discourse. And because some CEOs and Fund Managers (male and female) have children that sympathize with Greta Thumberg there is mounting pressure by the younger generation towards their parents questioning how sustainable they earn their money. The pure capitalism without or only with limited social responsibility seems to have brought the purpose of organizations back into the discussion. The question is, whether the purpose of an organization is only a ‘nice-to-have’ and merely a feel good factor or actually critical to the business? Larry Fink, CEO of BlackRock, the world’s largest Asset Management Company, answered that question clearly in a letter to CEOs last year, claiming that „… a company cannot achieve long-term profits without embracing purpose and considering the needs of a broad range of stakeholders.“

BlackRock has more than seven trillion US Dollars under management and this would suggest that its CEO’s view matters. Companies now know, that pursuing a purpose and good cause is not just a good statement in the annual report but a prerequisite in order to be a relevant investment target for Black Rock – and probably many other investment firms as well.

Environmental, Social and Governance (ESG) criteria for responsible investment are of increasing importance. The KfW, for instance, has been including ESG criteria in their investment decisions since 2008.

The independent network “Principles for Responsible Investment” (PRI) which is supported and was founded in 2006 by the UN provides a voluntary set of rules as a framework to incorporate ESG into investment decisions. It has been signed by more than 3000 (financial) institutions that adhere to the six PRI Principles when making their investment decisions. These Principles basically commit signatories to incorporate ESG into their analysis, decision making and overall processes, to seek disclosure by investment companies and collaborate as well as promote ESG externally. Many big investment companies are participants of PRI and it comes as no surprise that BlackRock has been amongst the signatories since October 2008 which is logically linked to their CEO’s letter about corporations with purpose.

But what exactly is a purpose?

Let´s have a closer look at what it actually means and also what impact it will have if an organization identifies, articulates and lives its purpose.

The purpose of an organization defines its contribution to the world. It answers two critical questions:

- What are we here for?

- What would the world be missing if we weren’t here?

It is not, as sometimes stated, an enterprise’s reason for being because the reason looks backwards and asks for the past events and circumstances that make the company do what it’s doing. The purpose goes beyond that, by looking into the future giving a corporation direction rather than trying to find the reason for being on the journey. This, however, is not to be confused with a target but is rather an aspirational direction that ignites a fire with everyone who is a stakeholder of the company, so not only its shareholders and management but also customers, suppliers, the entire workforce and the local community. The purpose needs to contribute to a greater good, something that helps to make this planet a better one in order to make people follow it passionately. In particular, the younger generations such as the Millennials and Gen Z have got this strong desire to do good at work and not only to make money to pay the rent.

By focussing everyone’s attention behind one worthwhile direction, the purpose also creates a sense of belonging. Working towards achieving the purpose, means success for the company and at the same time pursuing a good cause. Milton Friedman would certainly challenge that statement but there is evidence of a positive correlation between showing social responsibility and pursuing a purpose on one side and being financially successful on the other.

Larry Finck is of the view that “Companies that fulfil their purpose and responsibilities to stakeholders reap rewards over the long-term” and a research paper by Harvard Business School (George Serafeim, “Public Sentiment and the Price of Corporate Sustainability”, HBS, 2018) states that a company’s positive sustainability performance leads to a higher valuation premium. So purpose and sustainability can make a company more valuable.

Companies with a strong purpose do also have an advantage in attracting talent. “Many people—not just Millennials—want to work for organizations whose missions and business philosophies resonate with them intellectually and emotionally.“ (Sally Blount, Paul Leinwand, Harward Business Review Nov/Dez 2019). The well-educated talents do not primarily look for an attractive remuneration package but require that their own philosophy of life matches their employer’s purpose. The “Generation Greta”, daughters and sons of the Baby Boomers, born in the 1960s, grew up in Western Europe in peace and financial security. When they leave universities to take over their parent’s generation’s jobs they will place sustainability and what their employer does to make the world a better place at the top of their priority list.

Consumers increasingly demand brands that communicate and live a purpose they can connect with. This development is accelerated by the fact that the millennials contribute a growing share to the overall consumption as they already represent 35% of the workforce (Black Rock, Larry Finck, Letter to CEOs 2019). And this proportion can only be expected to grow when Gen Z starts spending their sustainably earned money. How quickly consumer preferences will change, shows a study by Deloitte, that finds that already 55% of respondents “believe that businesses today have a greater responsibility to act on issues related to their purpose.” (Deloitte consumer pulsing survey conducted in United States, United Kingdom, China, and Brazil in 2019).

And, for many companies, sustainability as a key purpose driver is becoming a must. Danone, one of the biggest food companies in the world, aims to become an “Entreprise à mission” and obliges itself to adhere to certain ecological and social standards. (Lebensmittelzeitung, 27.11.2020).

This goes far beyond profit maximization, however, initiatives like the one Danone is taking, might as well boost profits. 28% of consumers consider the way a company treats its employees a factor that influences brand choice, 20% think environmental impact and 19% behaviour in the local community are important factors when they decide for a brand, according to Deloitte.

Against this background, it is not surprising that companies are discussing the topic currently and consider to ‘give’ themselves a purpose. There is an inherent risk, however, that it won’t work if the purpose doesn’t fulfil a few important criteria:

Authentic – if an organization’s purpose isn’t routed in its DNA and heritage and the business model does not support the purpose, the stakeholders won’t buy into it. Any “greenwashing” or business conduct that does not support the heroic words of the purpose do more harm than good. Ideally, the purpose is derived from the company’s founders and their spirit and is emotionally attached to the business already.

Simple – the purpose statement will be communicated to a variety of people, from the employees who know everything about the business to consumers and shareholders that take an outside perspective at the company. All of them need to understand and be able to buy-into the purpose so it has to be phrased straight forward and simple, reading smoothly.

Individual – a purpose needs to inspire and therefore needs to allow for broad thinking; too much of it, however, will make it interchangeable. A purpose that could be valid for all competitors in the same segment doesn’t differentiate. If it is too narrowly linked to the actual business, companies run the risk of creating another objective rather than a purpose. Therefore, it needs to be unique to the company and yet leave enough freedom to be inspirational.

So if a purpose makes an organization financially more successful, attracts new customers and helps to find the best talent, it will make it also more attractive to investors. Which means that Black Rock might actually be serious when they claim to be making the corporate purpose of investment companies a priority.

Since investors not only look to invest in certain business models and financial criteria but also in ventures that follow a defined set of values encapsulated in the purpose, congruence in this respect between investor and venture is gaining importance. This is why purpose matters and needs to be at the top of the executives’ priority list – in particular when they are seeking new investors.

About author

Daniel Einhäuser has 25 years of international management experience. After his master in business and economics, he worked for the German Reemtsma Cigarettenfabriken GmbH in various finance functions. From 2002 until 2013 he worked in London for Imperial Tobacco plc as General Manager for the North Balkan, as Commercial as well as Region Director for Eastern Europe leading a team of more than 2400 people in 20 countries. After three years as a partner of consulting company Mathias & Associates GmbH, he joined one of Germany’s largest brewery companies Bitburger Braugruppe GmbH as Managing Director for König-Brauerei GmbH, turning around their König Pilsener brand, one of Germany’s largest beer brands. Daniel has served as non-executive Board Member for Reemtsma Kyrgyzstan, Tutunski Kombinat Skopje, Reemtsma Ukraine and as an advisory board member for Just Spices GmbH. He is helping companies on strategy, brand building as well as to articulate their purpose. He is also an executive coach supporting leaders to become more effective in their work.