In his political role, Lončar saw from within that the country he fought for and loved was on the verge of disintegration, due to already significant disputes and differences within the political elite

by Dejan Jović

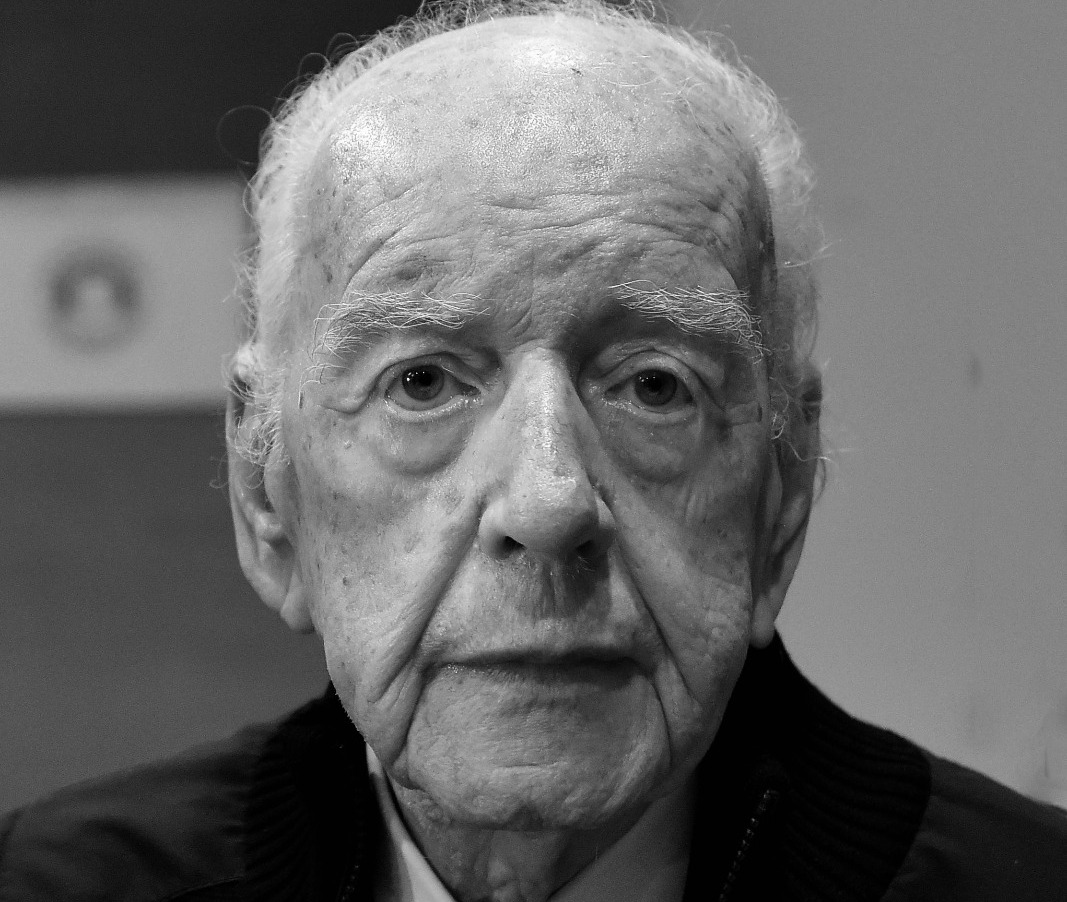

Budimir Lončar, the last federal secretary of foreign affairs of Yugoslavia (1987 – 1991) passed away in Preko on the Dalmatian island of Ugljan, where he was born one hundred years ago (1924). Lončar joined the diplomatic service in 1949, a year after the Tito-Stalin split when the foreign office needed new, young, devoted and open-minded people to represent the country, particularly in the West. Lončar was a suitable candidate. In 1942 he joined Tito’s Partisans in his native island and was twice wounded in battles for liberation of Yugoslavia. Immediately after the war, he was posted to the interior ministry and briefly to the Department for Protection of People (OZNA), the first intelligence service of post-war Yugoslavia, these days still preoccupied with fighting against the remnants of enemies in the forests and mountains of Croatian hinterland and Bosnia and Herzegovina. But like many other people from his native island and its surroundings, he saw himself as a „man of the world“, curious about other countries, and thus was keen to see the world. The foreign service was a natural place to be. He proudly accepted his first posting in diplomacy – as Consul and Third Secretary in the Yugoslav mission in the United Nations in New York. He travelled to the USA, as he would later testify, on Queen Mary and on 7 May 1950 saw to shores of New York, which he compared to Zadar, „only bigger“, as he said. In his childhood, Zadar was the first large city near Preko – and it was historically disputed between Italy and Yugoslavia. Interest in diplomacy, but also his participation in the antifascist movement (against Italian occupation of Dalmatia), Lončar later contributes to his desire to participate in the liberation of native shores and its returning to Croatia and Yugoslavia. Croatian fascists – Ustashe – he saw as being responsible for collaboration with Duce’s Italy, and thus as being massively anti-patriotic. For his whole life, he remained committed to anti-Ustashism, actively opposing historical revisionism and pro-Ustashe denialism.

While in New York, Lončar was chosen (being the most junior member of staff at the Yugoslav mission) to take minutes in highly secretive meetings of Yugoslav political and military leaders with their US counterparts – concerning economic but also military assistance to „America’s Communist Ally“ which dared to say „no“ to Stalin. In one of these meetings, he impressed Koča Popović, the legendary Partisan Commander, then the Head of the Yugoslav Army’s General Staff (1948-1953), the key negotiator with American military officials. Popović noticed that Lončar had a rare quality of „perfect memory“ – that he could remember the whole conversation ad verbatim, without the need to take notes or record (secretly) the meetings. When Popović was appointed (in 1953) the Foreign Secretary of Yugoslavia, he invited Lončar to his inner Cabinet, where he soon (in 1956) became the Head of the powerful GAP (Group for Analysis and Planning, the de facto analytical brain of Yugoslavia’s foreign policy). Lončar practically overlooked the border area between foreign policy and intelligence for eight years, until 1964. He founded the powerful and secretive SID – the Office for Information and Documentation, the de facto foreign intelligence service of Yugoslavia. In this role, he followed Koča Popović’s line that was suspicious of the official intelligence services of the Interior Ministry. He also supported Popović’s orientation of “permanent non-alignment”, even when Yugoslav leadership was keen to explore closer links with the post-Stalin USSR. For this reason, Lončar was always seen as being closer to the West than to the USSR and was never appointed to any diplomatic role in the Eastern bloc.

In 1961 he was directly involved in preparations for the first (founding) conference of the Non-Aligned movement, that began on 1 September 1961 in Belgrade. (Lončar died also on 1 September – 63 years since). He took part in all Summits of the NAM, and thus earned the title of „Mr Non-Alignment“. His network of influence in NAM countries was hugely impressive. Long after Yugoslavia ceased to exist, Budimir Lončar was in the position to lobby for the interests of his native Croatia and to open the doors for the business community, young Croatian diplomats and its politicians in the world beyond EU and NATO, because he was widely known and respected in what is now called „Global South“.

Lončar was Ambassador of Yugoslavia to Indonesia (1965 – 1969), to West Germany (1973 – 1977), and United States of America (1979 – 1984). These were difficult postings, exposed to permanent threats by hostile anti-Yugoslav emigres, in particular in Germany. He was a true civil servant, a top professional diplomat in the services of his country. Still, when he became first the Deputy Foreign Secretary (1984) and then the last Foreign Secretary of the „big“ Yugoslavia (1987 – 1991) politics became an unavoidable part of his job.

In his political role, Lončar saw from within that the country he fought for and loved was on the verge of disintegration, due to already significant disputes and differences within the political elite. He soon discovered that there was little he could do to change the course of events. He was only loosely embedded in the Party (then already nationalistically divided), so he used his international links hoping that the pressure from abroad could enforce compromise. Paradoxically, he now became more of a diplomat of the world in his own country, than a diplomat of his country in the world. He needed to use his diplomatic skills to prevent a war at home, having spent decades promoting peace, co-existence and economic development globally.

In 1961 he was directly involved in preparations for the first (founding) conference of the Non-Aligned movement, that began on 1 September 1961 in Belgrade

When the government of Ante Marković collapsed (in 1991) and the country entered the most violent phase of its history, Lončar moved abroad – to New York. These were difficult years for him. He lost his homeland (at least one of them, Yugoslav – whereas the other homeland, Croatian, was often hostile to him, as he refused to support the nationalist government of Franjo Tuđman) and even his profession (at least for a little while). Milošević’s “small Yugoslavia” (consisted of Serbia and Montenegro only) was also too authoritarian and too nationalistic for his taste, and – after all – Serb leadership considered him to be an obstacle to their visions of Yugoslavia and Serbia. It was the Secretary-General of the UN, Boutros-Boutros Ghali, his colleague and friend from a non-aligned Egypt, who offered support in these difficult years and appointed him as special representative of the UN in the NAM.

He remained committed to the ideals of liberation, economic and social justice, and global peace, and expressed his sorrow for not being able to prevent (how could he?) Yugoslavia from collapsing in horrible bloodshed

With Franjo Tuđman’s passing in 1999, Lončar returned to Croatia where he was welcomed by the new President (2000 – 2010), Stjepan Mesić, who needed his advice and assistance in foreign policy issues. He then became the Advisor to the President, which he remained – in a reduced capacity due to his advanced age – in the office of Mesić’s successor, Ivo Josipović (2010-2015) as his Chairman of the Council on Foreign Affairs. As President’s advisor, Lončar recovered some of his influence in overseeing the development of Croatian diplomacy.

Even in his tenth decade, until the very last days of his life, Budimir Lončar was of sharp analytical mind. Mild in his manners, astute in his judgments, with a brilliant memory and decades of accumulated wisdom, he was in daily communication with scholars (one of whom, Tvrtko Jakovina, published an authorized biography of Lončar in 2020) and foreign diplomats. In November 2023 he described his own life in two words: „anti-fascism and diplomacy“. He remained committed to the ideals of liberation, economic and social justice, and global peace, and expressed his sorrow for not being able to prevent (how could he?) Yugoslavia from collapsing in horrible bloodshed. He felt ashamed for all Yugoslavs for this.

Budimir Lončar died peacefully while swimming in front of his house in Preko, five months following his centenarian birthday. He will be remembered by many – in Croatia, all post-Yugoslav states and abroad, as one of the grandees of the world’s diplomacy, as the personification of the second half of the 20th century and the two decades of the 21st. His diplomatic style and elegant manners, as well as his analytical sharpness, will be very difficult to match.