Music reflects all the civilisational and cultural upheavals that may not be as clearly visible in society – and often, musical performers initiate such rapid changes that they can’t even keep up with them

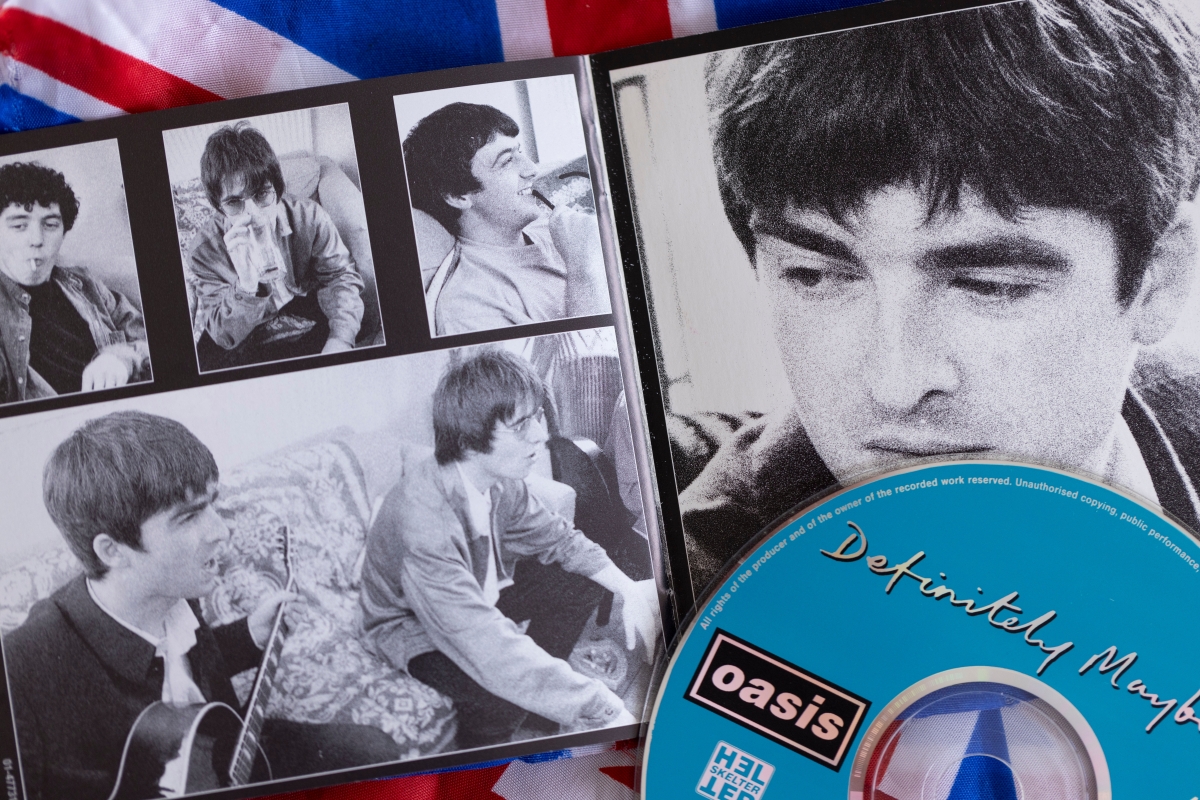

Photo: ToskanaINC / Shutterstock

First and foremost, this happens because there’s a build-up of energy just waiting to explode. The Beatles rallied the youth dissatisfied with the lack of social change in the UK after World War II, which they had expected. The Sex Pistols sparked punk because society was angry and frustrated – no future for you! Lana Del Rey, in her “depressive revolution” focused on introspection, said there’s “summertime sadness” and that we’re all “born to die.” Wait, isn’t summertime supposed to be full of joy, sun, and fun? Isn’t it born to be alive? Born to be wild? How is everything suddenly upside down?

Taylor Swift triggered a revolution when, as the “ordinary and respectable girl you’d proudly introduce to your mother, who’d approve of your choice,” she became the world’s best-selling music act. Amid all the bold, foul-mouthed, and half-naked women – Taylor! It was clear that the world was tired and in need of a new heroine. And now, with the “Oasis reunion” tour, and possibly a new album, the world is showing that it’s weary and in need of old heroes. It is politically incorrect, grounded, and with good songs along the way. The return of “lads’ culture” isn’t because it’s particularly amazing, but because we need it like water in the desert or a greasy burger after a hangover.

2009-2024

When Oasis split up in 2009, the world was a much more tolerant and peaceful place (even though the world now likes to think it has become more tolerant and peaceful, in its delusion), without the perpetually angry internet warriors cancelling this and that, calling for lynch mobs over a single word, act, or photo. These people have, in the end, pretty much “killed” many social networks, as a vast number of people have withdrawn from the internet, only observing what others do, not daring to do or post anything, to comment on anything, for fear of being judged. In 2009, the world was, therefore, a much more normal place. And in that normality, Oasis, who had already been around for 15 years, may not only have ceased to be modern but no longer necessary. So, they easily fell apart.

15 years later, the world without Oasis has changed so much that 2009 now looks like the ‘Age of Pericles’

Fifteen years later, the world without Oasis has changed so much that 2009 now looks like the “Age of Pericles” – the quality of music has significantly declined, and this shift happened for several reasons. One of them is that by 2014, most listeners were equipped with smartphones, with constant internet access, making music listening superficial, ubiquitous, streamed, and cheap. This ruined new creators, whose music became devalued. The music industry, as Noel Gallagher astutely pointed out, doesn’t like musicians who are high or drunk at noon on a Tuesday – they’re too “unreliable” – so Harry Styles is preferable, someone you can tell, “Keep your rebellious tattoos, put on this dress, sing the songs we’ve written for you, stay quiet, and go home!” That’s the kind of rebellion that’s allowed, controlled. And the listeners feel that. And they’re suffocating.

Come to my door and tell me I’ve been cancelled!

Liam Gallagher chimed in here – with his disdain for cancel culture. How can someone hide behind a screen and say they would ban someone’s right to speak or express themselves? Come to my door and tell me I’ve been cancelled, to my face. If you dare. But you don’t. This is how Liam summed up the cowardly civilisation we find ourselves in. Where no one is allowed to be ordinary or “moderately flawed,” where everything is swarming with “moral giants” and the aforementioned internet warriors. The fight against cancel culture is a civilisational achievement of Liam and the crew.

On the other hand, Oasis was known in the world of Britpop as “working-class Northerners,” unlike Blur, who came from London’s middle-class art schools and whose members openly leaned towards Margaret Thatcher and the Tories, using “mockney” to gain street credibility. As Jarvis Cocker from Pulp said, two very important things in UK society are sex and class. That’s why their most successful album is called Different Class, and why the song Common People is about the “impossible” love between two people from different classes. Suede sang about London suburbs and council estates but without much trauma from violence, while the three Gallagher brothers survived the trauma of a violent alcoholic father of Irish descent. Perhaps that’s why they never knew how to communicate without immediately turning to aggression, but at least they showed (two out of the three, as the third isn’t a musician) that you can come from a poor background and become a hit-making musician, rise, and become better than you were, forgetting the beatings from a father returning from the pub. And that is a civilisational achievement they carry forward.

Today, most “escapes from poverty” in music are told through wannabe gangsters in rap and hip-hop, where the crew from the poor neighbourhood is glorified, but they dream of a world of VIP lounges and champagne, speaking of prostitutes, drugs, and easy money. The Gallagher brothers made a ton of money (and will continue to), but they didn’t earn it easily, nor did they flaunt it in their songs or images. Liam patented the design of the parka jacket, and you often see him jogging in the streets, while Noel designed the kit for his beloved Manchester United and is often in the stands. They seem like they could be your neighbours, not people you’d need to pass through three rounds of bodyguards just to see. And that is an enormous civilisational achievement they carry forward.

Punchline: It’s a refreshing contrast

The essence is this – Oasis is not sanitised, unlike today’s pop products. They show new generations that it’s possible to be both a normal person and a star at the same time, lifting the anxiety-inducing weight from young people’s shoulders – you don’t need to be Instagram-perfect or TikTok-flawless. You can look like you just rolled out of bed or stepped out of a pub. Which probably just happened. And that’s yet another civilisational achievement of Oasis.

Also, they’re a band – not a solo artist or a duet. Over the last 15 years, the presence of bands, groups of people performing together – even if they’re all singers, like in the boy bands of the ’90s and 2000s – has dramatically decreased. Once again, this shows young people the power of unity. In a lonely civilisation like the one we’re increasingly becoming, where everyone stares at their phones, even on beaches and in clubs, taking a photo or video and instantly posting it, then checking back 10 minutes later to see how many likes we’ve got – in a world where it’s “me and my phone” as best mates, we realise how important it is to have a crew. Even if you argue. And unity, a somewhat forgotten concept, is something Oasis is bringing back to the big stage – which is a civilisational achievement.

In an era when we’re all hesitant to express an opinion because the algorithms might ban us for a while, the “lads” say what they think. That’s incredibly liberating in a time when everyone is “walking on eggshells” to avoid saying the wrong thing, being cancelled or having their reach reduced due to some “misstep.” In this age of endless self-censorship and apologies, lad culture feels almost like a remedy or antidote. Perhaps this is the greatest civilisational achievement of Oasis’s return.

We look forward to a better, less sanitised, more relaxed, and politically incorrect world

Finally, is the hype around the Oasis reunion overblown and out of place? Well, no. Younger Millennials (Gen Y) and Generation Z respond best when hype is present. Let’s remember the slightly forgotten Kate Bush and Running Up That Hill, which went viral thanks to Stranger Things, turning her into a millionaire in her later years.

We look forward to a better, less polished, more relaxed, and politically incorrect world. Today, bands like Oasis, Suede, Nirvana, or Rage Against the Machine wouldn’t even be allowed to become famous and so influential. Let alone wealthy. But when it comes to “the giants of the past,” they’re impossible to stop. On one hand, they’re already so established and well-known that it only takes one snowball to roll down the hill to start an avalanche. Secondly, the music industry, the infamous Ticketmaster, and others aren’t so foolish as to miss the chance to cash in on the Oasis comeback, no matter how unpredictable the squabbling Gallagher brothers may be. Money talks, and this time, it must seize the opportunity to make money off a performer who directly works against the trends that money in the music industry helped create.

That’s why it’s so important on a cultural level. That’s why the return of Oasis is a civilisational event. After 15 years of the world’s “decline” from a sociological perspective (no more personal flirting, only dating apps; an image of ourselves that others hold is more important than the truth; fears of saying something that could lead to ostracism, etc.), Oasis is bringing us back to where we made the wrong turn – as Bugs Bunny would say, “at Albuquerque.”

Text by: Žikica Milošević