There is no haven for thieves

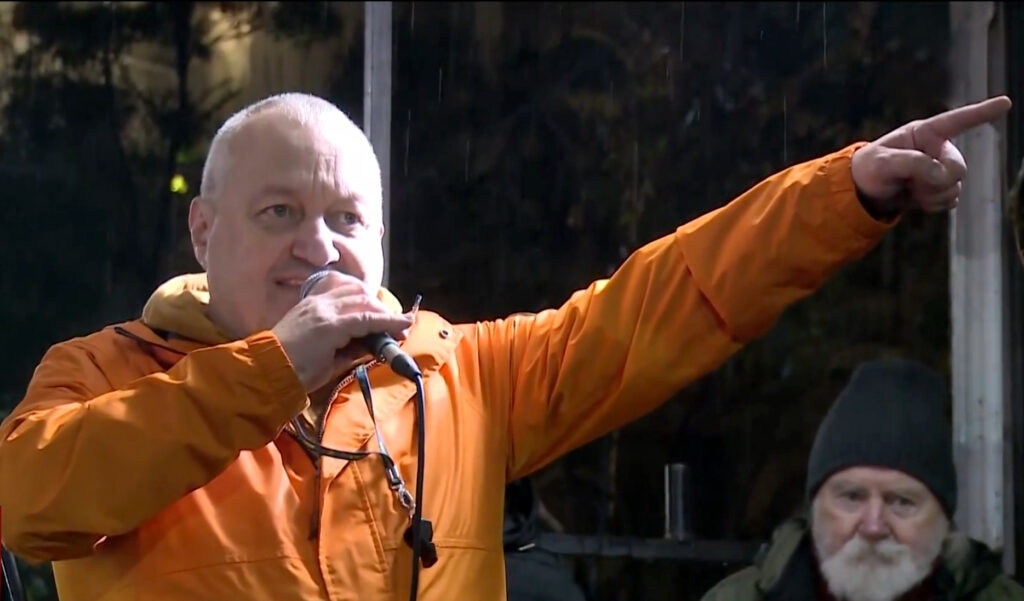

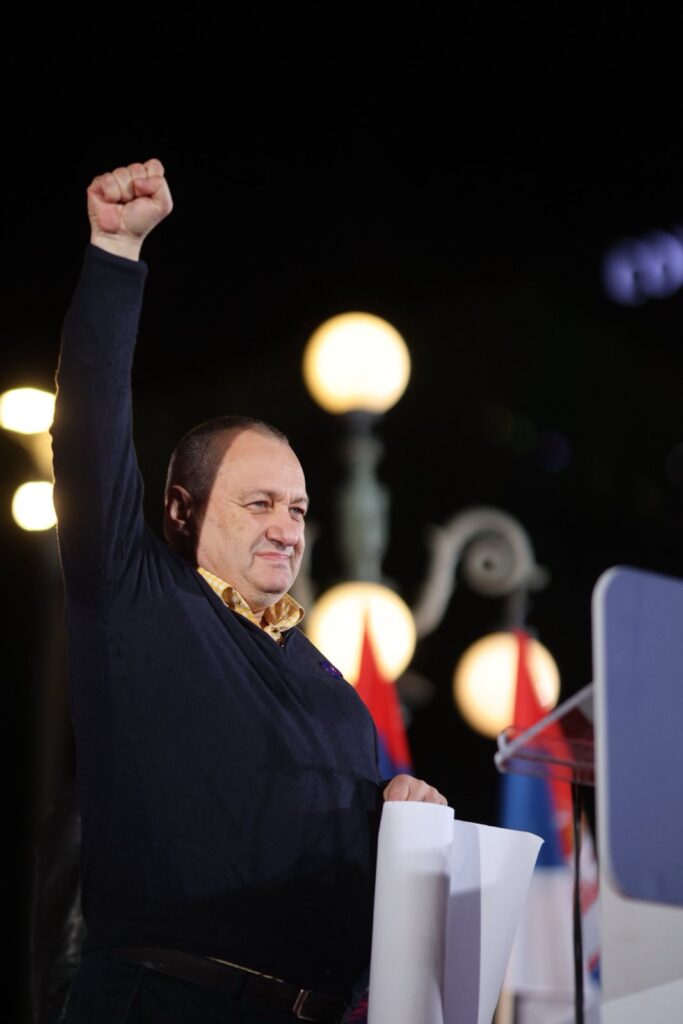

At a moment when student protests are shaking Serbia, demanding justice and systemic change, the Democratic Party has elected a new leader—Srđan Milivojević, a former Otpor activist who once stood at the forefront of the fight against dictatorship. Now, as the country faces another wave of political and social unrest, he takes on the challenge of reviving the party, reshaping the opposition, and channelling the energy of the protests into a broader movement for change. In this interview, he discusses the lessons of the past, the stakes of the present, and the fight for Serbia’s democratic future.

At a moment when student protests are shaking Serbia, demanding justice and systemic change, the Democratic Party has elected a new leader—Srđan Milivojević, a former Otpor activist who once stood at the forefront of the fight against dictatorship. Now, as the country faces another wave of political and social unrest, he takes on the challenge of reviving the party, reshaping the opposition, and channelling the energy of the protests into a broader movement for change. In this interview, he discusses the lessons of the past, the stakes of the present, and the fight for Serbia’s democratic future.

You entered politics in the 1990s as a member of Otpor during the protests against Slobodan Milošević. It is inevitable to ask about the many parallels that come to mind: student protests then and now, Milošević and Vučić, Serbian society in the 1990s and today.

It isn’t easy to compare these two periods. Slobodan Milošević has little in common with Aleksandar Vučić, except that both pursued policies that were catastrophically harmful to Serbian national interests—policies that can rightly be described as treacherous and criminal. Both had an overwhelming desire for unchecked and unlimited power. They viewed authority as a set of privileges for themselves and, above all, their families, with whatever remained going to their party loyalists—and there was plenty left for them.

They equated their rule with the state itself. Anyone who dared to criticise their regime was branded an enemy of the state and treated accordingly. However, what significantly differentiates these two eras of autocracy and absolute rule is the nature of their governance. Slobodan Milošević was the very embodiment of evil, its worst possible manifestation. Aleksandar Vučić, on the other hand, is a farce. And a farce can sometimes be more dangerous than the original because a fraudster deep down knows he is just a grotesque caricature, surrounded by people who genuinely believe that buying diplomas and academic titles has given them the knowledge, skills, and expertise those qualifications are supposed to represent.

Vučić, like Milošević, has become intoxicated with power. But these are people without any moral restraint. Both convinced themselves this was precisely how the people wanted them to be. However, when faced with the logical question—if the people love you so much, why do you need to rig elections?—they have no answer. They are aware that their closest associates fear them, that free-thinking people despise them, and that those misled by propaganda may love them, but only for as long as that propaganda, reinforced by petty bribery, remains compelling.

Nevertheless, despite the horrors it endured, Serbian society seemed much more resilient in the 1990s. We entered the crisis of the 1990s from the relatively high standard of Ante Marković’s era. The worst affected were intellectuals, professors, and people who struggled to adapt to hyperinflation, shortages, and sanctions—people raised to believe they were part of an organised system in which their education and social position secured their livelihood and advancement. That is why they led the rebellion.

At the beginning of his rule, Milošević stirred national sentiment while suppressing democratic and civic values. That is why we ended up where we did, concluding the 20th century in a worse position than we entered it. We had started the century near the bottom of Europe, assassinated a ruler, overthrew a dynasty, and then fought three wars to regain our freedom at great cost. A small peasant nation played a crucial role in the Great War, rising like a phoenix from a grave reserved for failed and extinct peoples. We became a great and respected nation worldwide because of our suffering, bravery, chivalry, and humanity.

We emerged from World War II with the reputation of a people who had survived genocide in the Independent State of Croatia, only for Milošević’s reckless policies to turn us, within a few short years, from a nation of victims into a nation of perpetrators. Centuries of struggle for freedom, paid for with over three million lives, were squandered by Milošević’s treacherous and senseless policies in exchange for a brief period of personal power.

Students immediately rose against Milošević. We launched the first protests against him in the Student City in 1988. It took 12 years of struggle and tremendous suffering to overthrow the dictator. People had grown tired of being heroes in lost wars.

Today’s environment is entirely different from what we faced in the 1990s. Back then, students had to fight to survive. The generations of students after 2009, thanks to the abolition of visa restrictions, took their passports and left Serbia as soon as they graduated. They refused to be guardians of missed opportunities.

The current generation of students has chosen to be remembered as worthy descendants. Serbia must be proud of them—proud of this generation who will be our society’s driving force and the engine of our progress.

The regime stands exposed—we no longer participate in the illusion of parliamentary democracy

As someone who participated in the 1996/97 student protests, I knew that no real change would come to Serbia until the students rose. Do you share this view, and do you think the current student protests have the potential to transform society and lift it out of apathy?

Students have not only awakened society from its anaesthetised state of apathy but have also reignited hope that people are willing not just to replace those in power but to restore the fundamental values of our society. Here, even the most basic moral norms have been destroyed. In our society today, being honest is seen as foolish, according to the imposed views of the ruling elite. To be uncorrupt is to waste an opportunity by the ethical code of those in power whose morality has been amputated. Speaking the truth is dangerous because this society has forgotten what truth is.

The greatest challenge will be raising future generations on the ideals of freedom, for in Serbia today, according to the ruling party’s mindset, being free is akin to how communism was understood by the young boy in the film The Time of Miracles, based on Borislav Pekić’s novel. In one scene, a village teacher asks the boy what communism is.

“Communism is when I have food to eat every day,” the boy replies.

“Only you?” the teacher asks.

“Only me!” the child answers.

“Just that?”

“Just that.”

Today, we must teach young people what freedom and democracy mean. We must help them understand that freedom does not mean doing whatever one pleases. People must grasp that individual freedom is primarily limited by the freedom of others—not just by laws and the Constitution.

And they must understand that rebellion is a constitutionally guaranteed right whenever lawlessness threatens to take hold.

Why did the crime committed on 1 November 2024 at the Novi Sad railway station finally awaken public awareness when there had already been dozens of similar incidents before—perhaps with fewer victims but rooted in the same seed of evil?

Why did the crime committed on 1 November 2024 at the Novi Sad railway station finally awaken public awareness when there had already been dozens of similar incidents before—perhaps with fewer victims but rooted in the same seed of evil?

Both the tragedies in May and, even more so, the crime in Novi Sad showed people that no one can live in a dysfunctional society and claim, “I don’t care how my country is run; politics doesn’t interest me.” The idea of having one’s little world surrounded by a Chinese wall, untouched by anything outside of it, does not hold in a society like this.

No small world is disorganised; even less so is safety or security. No one is safe because evil will come knocking at your door—even if you never invite it in. The reckless arrogance and shameless impunity of those at the top of the regime, who responded to every logical question from citizens or the opposition with a dismissive “So what?” will come at a high cost for our so-called progressive aristocracy.

Now, the reckoning has arrived for every crime that was ignored or brushed aside—for Savamala and the toll station, for Oliver Ivanović, for the helicopter crash, for Jovanjica, and for everything that has happened since.

There can be no retreat or surrender—this is the last moment for us to stand together

How can peaceful (Gandhian) protests lead to the activation of institutions and their return to constitutional frameworks—since change is impossible without functioning institutions?

Only by building independent institutions can we move our society forward. This process must be led by those free from the influence of day-to-day politics. Political dictates should not shape Independent institutions but must function as a service to the citizens.

Next week, we will witness yet another absurdity on Serbia’s political scene—Ana Brnabić will convene a session of the National Assembly to discuss laws proposed by a fallen government, with ministers in a technical mandate presenting them.

What is the role of the opposition in the student protests, and how do you and other opposition leaders support them without causing harm?

Student protests are independent of political parties and must remain that way—even if they begin to express specific political aspirations. However, the opposition has been fighting this regime for twelve years, and these protests initially started at the opposition parties’ call.

Our struggle has now taken on a new dimension, as we no longer participate in anything that creates the illusion of parliamentary democracy in Serbia. The regime stands exposed.

You were recently elected as the president of the Democratic Party. How important is this party for Serbia, and why must it regain its former strength? How do you plan to restore its influence, especially considering its long decline and fragmentation, which has left it struggling to pass the electoral threshold today?

At the recent Electoral Assembly of the Democratic Party, I was mandated to restore the party as a guarantor of everyday life in Serbia. This vision received the strongest support at the Assembly. Its implementation begins with bringing in many capable, accomplished professionals—individuals of unquestionable authority and reputation in society—to engage in politics within the Democratic Party. Integrating other political parties and influential civic associations into the party is also part of this strategy for victory. The Democratic Party’s logo remains the most powerful symbol of freedom and modernity in public life. I have launched a call to action, inviting everyone who wants to fight for such a Serbia to join us.

My goal is not to create the biggest and strongest opposition party but a party capable of defeating the criminal regime in power, restoring normality to our society, delivering justice, and establishing the institutional foundations for a decent life for decent people. I aim to lead integrative processes and strengthen the Democratic Party so that it becomes the driving force behind future change. I want the party to be open to all political and social organisations, civic initiatives, and individuals who share our values and ideals. We are opening the party to spread the political ideas and principles we have upheld for a century.

One does not need to be a member of the Democratic Party to be a Democrat, but one must be a Democrat to be a member of the Democratic Party. However, to fight against Aleksandar Vučić’s regime alongside the Democratic Party, one does not have to be our political or ideological ally. It is enough to recognise the urgent need for this regime’s removal and the rebuilding of Serbia as a free, democratic, and lawful state—and to be willing to fight for that goal. This is important to stress, mainly when some opposition voices display elitist arrogance or disdain toward those who are only now joining the protests or publicly supporting students and their demands after years of silence.

That is the wrong approach, both pragmatically and strategically. What we need right now is the exact opposite. We do not need an exclusive club of regime critics; we need an open resistance movement capable of forming the broadest possible front of brave and united individuals ready to stand against the inhumanity that has taken hold. That is why my campaign slogan was: The Time for Resistance Has Come. This was not a reference to the Otpor! I was once part of the movement but to resistance in the literal sense of the word. There must be no retreat or surrender in the face of the physical and psychological repression the regime is imposing on Serbia’s citizens. This is the last moment for all of us to stand together.

Under the banner of freedom, everyone is welcome. The recent elections within the Democratic Party proved that fair and honest elections are possible in Serbia and set an example of what elections should look like. Free and fair elections, conducted under the principles of a democratic society, are essential for Serbia’s recovery and for restoring normalcy in our country.

Free and fair elections are essential for Serbia’s recovery and return to normalcy

Beyond its crucial role in the democratic changes that took place in Serbia after 2000, the Democratic Party is also partly responsible for the totalitarian regime we live under today, given that many of its former members have become key figures in the SNS government, and that some of the post-Đinđić DS methods have served as a blueprint for the current regime’s operations.

I completely disagree with this view. Those who left the Democratic Party to join the ruling mafia were never indeed members of the Democratic Party—they were members of whoever was in power. The only connection between Zoran Đinđić, Serbia’s first democratically elected prime minister, and this regime lies in its leaders’ public threats before his assassination and their celebration of his murder—marked, in Aleksandar Vučić’s own words, by his third drunken binge.

There will never again be a bridge for political turncoats to return from the dark side to the light. On the contrary, they, too, will face lustration, and those who have broken the law to amass enormous wealth will be prosecuted.

The Democratic Party has a clear message: there is no haven for thieves. A party membership card—especially from the ruling party—does not grant immunity from criminal responsibility. Justice will be served.