Those who seek individual attention do not do well in the royal family

THE BRITISH monarchy’s record of absorbing outsiders is patchy. In recent times, it has had one outstanding success (Kate Middleton, Prince William’s wife), several modest successes (including Sophie Rhys-Jones, Prince Edward’s wife), a few questionable results (among them Sarah Ferguson, Prince Andrew’s ex-wife) and two stunning failures (Diana Spencer, the late Princess of Wales, and Meghan Markle, Prince Harry’s wife). On March 7th the world was treated to dramatic evidence of the latest disaster, in the form of an interview which Prince Harry and Ms Markle—the Duke and Duchess of Sussex—gave to Oprah Winfrey, one of America’s most famous talk-show hosts.

The revelations in the interview were in part familiar. The loneliness of which the duchess spoke, and the lack of support from within the “firm”, echoed Princess Diana’s experience. “This was very, very clear,” she responded to a question about whether she was having suicidal thoughts. “Very clear and very scary. I didn’t know who to turn to in that.” The most explosive new factor was race. The duchess said that when she was pregnant with her son Archie, her husband had told her there were “conversations about how dark his skin might be”, though both declined to say who had raised the issue. Another big difference between the prince’s mother and his wife is that, in this case, the wife has left the country and taken her husband with her—as Wallis Simpson, the last American to marry a senior member of the royal family, went off to Paris with Edward VIII. The painful impact of Prince Harry’s decision to leave also came out in the interview: for a while, the prince said, his father stopped taking his calls.

These revelations indicate what is presumably part of the purpose of the interview. There has been plenty of criticism of the couple’s decision to leave Britain for California, and of their attempt to retain some of the privileges of royalty while doing so. An interview with Ms Winfrey—who is also a friend—is a good way of putting their side of the story. Such exposure should also enhance their celebrity and popularity, on which their income depends, now that they have been financially cut off by the royal family. But it also represents a burning of bridges. For Meghan at least, there will be no going back.

The palace issued a neutral, conciliatory response: “the issues raised, particularly of race, are concerning…they will be addressed by the family privately.” But somebody, whether inside or outside the royal household, launched a pre-emptive strike. After the interview was recorded, but before it went out, a complaint made against the duchess in 2018 by a senior member of staff was leaked to the Times. Jason Knauf, at the time press secretary to both princes, wrote to Simon Case, then Prince William’s private secretary and now head of the civil service, saying that she had “bullied two PAs out of the household”, and was bullying a third. He was “concerned that nothing will be done”—rightly, since it appears that nothing was, indeed, done.

Beyond the sniping from both sides, the fundamental problem, with which Princess Diana struggled, is clear. Being a royal is about serving an institution. It does not work for those who crave individual attention. The only way of doing the job properly is through self-effacement, at which the queen, who has not said a single interesting thing in public in her 70 years on the throne, has excelled. That’s not because she is a boring person, but because she understands the demands of the job. The Duchess of Cambridge, aka Ms Middleton, is, similarly, brilliantly bland. The Duchess of Sussex is not; and her complaint in her interview that while she was a royal she was not allowed to talk to Ms Winfrey without other people in the room demonstrated her failure to grasp the need to subsume individual needs in those of the institution. Given the potential impact of such an interview on the monarchy, it would have been bizarre for the household’s communications chiefs to allow her to negotiate with the world’s most powerful interviewer by herself.

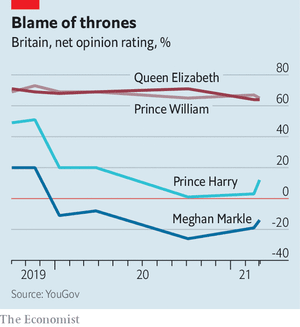

As it is, the duchess has done the interview on her own terms. It may do the couple some good; it may do the monarchy some harm, but probably not much. The queen and Prince William are considerably more popular than the Sussexes, whose ratings have declined (see chart). Those Britons who care about this row side, by more than two to one, with the palace. And the monarchy’s popularity seems impervious to such troubles. Even during the split with Princess Diana, it barely budged. That may, of course, have a lot to do with the queen’s popularity. When she dies, things may look different.

![]() From The Economist, published under licence. The original article in English can be found on www.economist.com

From The Economist, published under licence. The original article in English can be found on www.economist.com