How did a town in Istria become “Belgrade on the Sea” in the 1950s and what did Miša Jovanović write about it in his book “Goodbye, Old Rovinj”? Who came to the 14th Weekend Media Festival? What did people talk about in the panel discussions and what happened on the Festival’s margins? Why are we going to drink Malvasia and eat cod again next September while lamenting about people who pitted us against each other?

“I would give everything to see Bajaga live in concert,” the shop assistant adds. I tell her to sit on the stone fence near the waterfront in front of Tvornica, in which courtyard Bajaga will be holding a concert, so she can listen and enjoy the music of this Belgrade rock musician, whose popularity in Croatia has not waned at all.

Bajaga’s performance at this year’s Weekend Media Festival was sponsored by Una TV, a still-mysterious regional project backed by Dejan Jocić, former head of Belgrade’s Prva TV (Prva/Una?) and later almost director of Nova TV, which despite being promised by certain top officials that it would be given a national broadcasting frequency in 2013, was not assigned one. Jocić participated in the Festival’s panel discussion “Future TV – Next Level”. However, there was no mention of Una TV on his name tag, but rather the name of the German investment fund called Foundcenter Investment Berlin. While sipping on my coffee, sitting on the concrete terrace of the Maestral Hotel, right next to the waterfront, I heard that Una TV would open offices in Banja Luka, Sarajevo, Belgrade and Zagreb and would focus mainly on entertainment content (a couple of weeks ago, it was announced that the Croatian singer Severina will be one of the celebrities working for this TV station).

Conspiracy theorists and self-proclaimed experts swear that Igor Dodik, Milorad Dodik’s son, and the Republic of Srpska’s Telekom, are behind all of this and that the whole endeavour is another soft power project which aims at unifying all Serbs. There will be time to think about it when the festival visitors cure their hangover from the last evening of the festival, during which Bajaga’s songs echoed long into Rovinj’s night: “Moji su drugovi žestoki momci velikog srca i kad se pije i kad se ljubi i kad se puca…” and people, as always, forming the conga line and dancing around the courtyard of the former tobacco factory.

We arrived in Rovinj on Friday at dawn after a six-hour drive from Novi Sad which started after midnight. We enter the Grand Park Hotel which has a lovely view of Rovinj’s Old Town, perhaps one of the most beautiful on the Adriatic. The panel I moderate is the first on the schedule on the first festival day and after having a strong coffee, I slowly head towards the Tobacco Factory, a ten-minute walk. As I am walking, I am thinking about the first festival, which was held in mid-September 2008, just a few days before the outbreak of the global economic crisis. Back then, I took part in a panel talking about celebrity magazines and one of the guests was a Facebook representative for Europe. We talked about the experiences of that social network that was just “breaking through” on our regional market.

Exactly 10 years ago, I was one of the panellists in ‘The Food that Feeds Media’ panel. I talked about the success of our magazine “Pošalji Recept” which was based on housewives over the age of 50, who don’t use the Internet, sharing their best culinary experiences. I called the magazine back then “Facebook for baby boomers”.

The love that Belgraders have for this once industrial town is everlasting and despite thousands and thousands of tourists coming to Rovinj from all over the world every year, the town still proudly bears the epithet – “Belgrade on the Sea”.

The panel I moderated this year is called “To aim at a target or to shoot from a shotgun: special interest print vs mainstream print.” A panellist from Serbia, Josip Ašik, took part in the panel’s first segment. Ašik and a group of his friends from Zemun make and print the magazine called American Chess Magazine. The printed version of the magazine is sent to the United States, where it is distributed to chess fans. When Tomo Ricov, the director of the Weekend Media Festival, read an article about Josip on my Facebook profile a few months ago, he immediately wanted him to take part in this year’s festival.

The other two panel participants helm Croatian mainstream dailies – 24 Sata and Večernji List. While I was talking about the differences between the Croatian and Serbian media scene today, the title of a panel from the 2011 festival – “There are so a lot of nice things that I cannot say” – popped into my mind. Back then, the talk was about restrictions on tobacco and alcohol advertising. During this panel, the famous line uttered by the actor Boris Dvornik in the Velo Misto TV series was running through my head because, in principle, I do not like to speak badly about the country I come from when I am at conferences abroad. Inevitably, the impression is that the current situation in the news media (daily newspapers, web portals and television) in Serbia has never been so far removed from the European and even regional standards. Ivan Buča, the editor-in-chief of 24 Sata, says that he receives notifications from the online versions of all Serbian daily newspapers and that sometimes it seems to him that the identical spin news is published with a few seconds difference in each of these newspapers, like in Orwell’s dystopian novel.

Dr Manfred Spitzer, the author of the bestsellers “Digital Dementia”, “Loneliness, the Unrecognized Disease” and “The Smartphone Epidemic”, was the international star of this year’s festival, which was held under the slogan “Long Live Life”. In the last ten years, smartphones have conquered the world with great speed and changed the everyday life of four billion users like no other technical innovation before. From morning to evening, at work and in private life, nothing seems to work without a smartphone. Dr Spitzer asks what price do we pay for using smartphones? It is as if they are thought of only in a positive context, and few care about the negative consequences on our thinking, feelings and actions, our health and our society. Both investors and entrepreneurs have been warning about the health consequences of excessive use of smartphones.

CEO of Apple recommends that smartphones should not be used in schools, French President Macron has completely banned them from schools while South Korea has had laws in place for years that protect young people from the worst consequences of using mobile phones, because, when used without any restrictions, they negatively affect health, education and society as a whole.

It is interesting to note that two announced festival participants, both big names, so to speak, did not appear – Jovana Joksimović, who was supposed to take part in the panel on “infotainment”, and Galeb Nikačević, who was supposed to talk about podcasts.

Before the start of the panel “How festivals change destinations”, I am sitting in the garden of the Maestral Hotel with two of the panellists – Jovan Marjanović from the Sarajevo Film Festival and Ivan Petrović from the Exit Foundation. Their two festivals were very successful this summer despite the pandemic-induced challenges. As we were chatting, my colleagues in Novi Sad were organizing Oktoberfest. Talking about it, I am under the impression that people who were vaccinated against the coronavirus are much less bothered if unvaccinated people come to a mass event than the so-called anti-vaxxers, once these festivals announce that the only people they would be letting in would be those who have of proof of vaccination, the so-called ‘green’ certificate. The introduction of COVID passes caused a torrent of protests and insults on social media, with comments like “It’s not a long way to go from green certificates to yellow armbands. This is fascism!” and the like. I am quite sure that this phenomenon (absolute confidence that anti-vaxxers have in the rightness of their attitude) will one day be the subject of serious scientific studies. By the way, the black armband from the beginning of the story was given to the vaccinated festival-goers, while the green armband was worn by the people who submitted a negative PCR test.

People from Belgrade nurture a special kind of love for Rovinj, which seems to have become another emotional toponym of the Serbian capital, along with Dorćol and Vračar

On the second day of the festival, as I am sitting in the courtyard of the former Tobacco Factory, an example of an excellently preserved industrial heritage, with my colleagues Dragan Močević from Banja Luka and Dejan Ljuština from Zagreb, we are talking about the regional scene. This festival, which has been taking place every September in Rovinj, for the past 13 years (except last year), reminds us that stories about regional cooperation between countries, economies and media that were once a part of one country are not just an empty phrase used by certain people to obtain EU funds. Just like in the former Socialist Federal Republic of Yugoslavia, every country has something that is “better than the other”; there is always something to see peeking over “the neighbour’s fence” and learn from it. The magnetic attraction between men from Belgrade and women from Zagreb and women from Belgrade and men from Dalmatia is not just an urban myth.

By the way, people from Belgrade nurture a special kind of love for Rovinj, which seems to have become another emotional toponym of the Serbian capital, along with Dorćol and Vračar. As the Italians moved out of Rovinj, the town, with its many empty houses and apartments, has become an “easy target” for Belgraders who have been buying real estate here since the late 1950s.

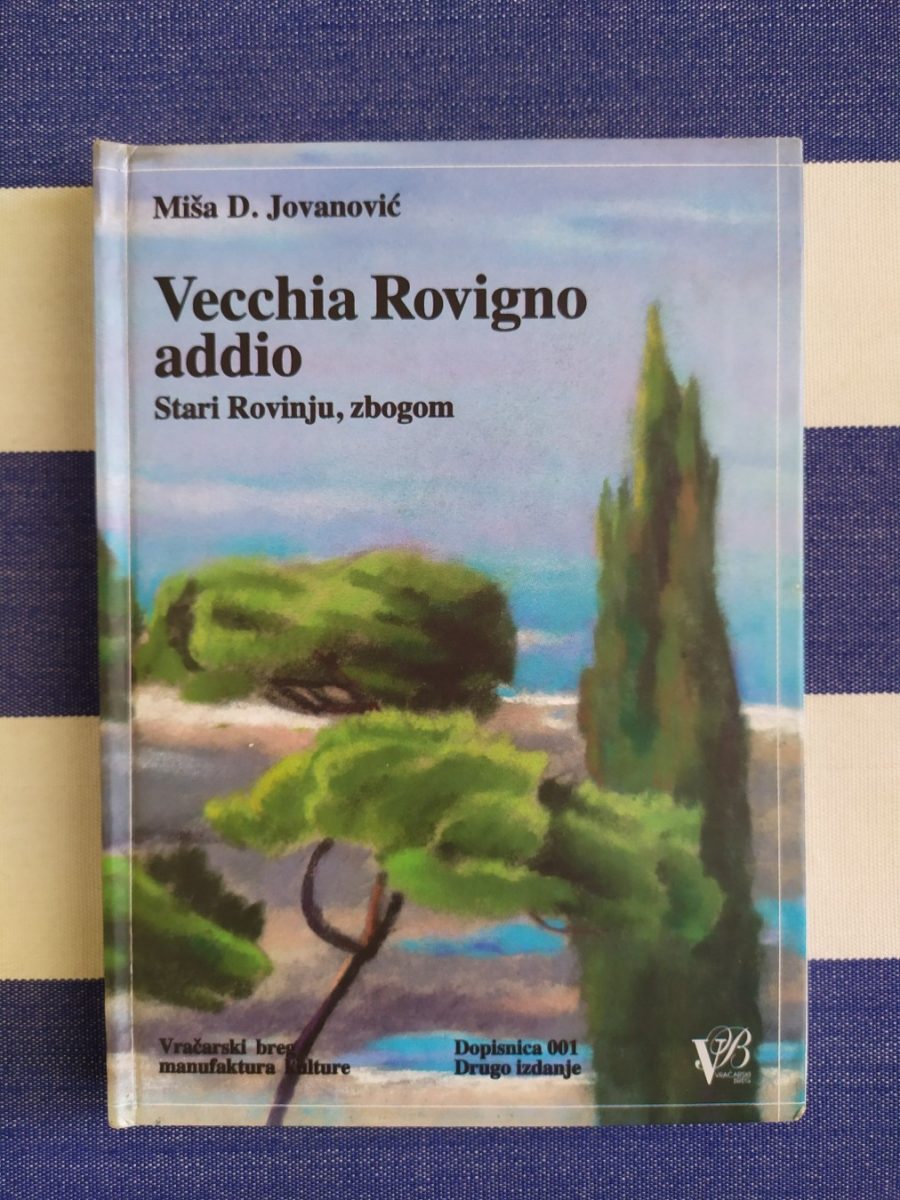

One of the first Belgraders to come to Rovinj, back in the 1950s, was the lawyer Miša Jovanović who, together with his older and more famous contemporaries (Mića Popović, Mihiz, Antonije Isaković…), became a trademark of Rovinj. Tormented by nostalgia for Rovinj, which was his second hometown for years, he wrote the book “Goodbye, Old Rovinj!” (“Vecchia Rovigno, Addio!”), which he published by himself and distributed among his friends.

Just like in the former Socialist Federal Republic of Yugoslavia, every country has something that is “better than the other”

At the beginning of the book, Miša Jovanović talks about arriving in Rovinj by train and mentions the town of Kanfanar, the people who had spent their summers in Rovinj, which was a must-see destination in the 1960s and 1970s, and his feeling of nostalgia. “How did people get off the train, which was stationary only for a few minutes on its way to the final station in Pula?! Suitcases were often thrown out the window, and people jumped from the high stairs onto the gravel floor that was a staple at almost every railway station in Yugoslavia,” he writes. That is how his first encounter with Rovinj began. “Then you come to a town where there is no beach and where everything smells like cigarettes and fish (Rovinj was known for its Mirna fish factory and TDR tobacco factory), a town that you always come back to,” Miša writes.

The love that Belgraders have for this once industrial town is everlasting and despite thousands and thousands of tourists coming to Rovinj from all over the world every year, the town still proudly bears the epithet – “Belgrade on the Sea”.

I did not miss out on my afternoon ritual of cycling along the coast to the Polari camp. As I walk along the perfectly arranged and maintained coastline, I stop next to a sign which, under the inscription “Zlatni Rt Forest Park”, features a black and white photo of Count Johann Georg Huetterott, the father of the famous Baroness Huetterott, whose tragic fate on Crveni Otok (the Red Island) I wrote about a month ago. Count Huetterott started preparing the forest for the opening of a climatic health resort called Cap Aureo (Golden Cape) here. This job was not finished since he committed suicide in 1910, desperate because of the debt he had accumulated while financing the construction of the Viribus Unitis ship, commissioned by the Austro-Hungarian Navy.

I pass by the part of the coast where there are hundreds of “towers” made of stacked stones and I wonder again how it is possible that, all these years, not a single vandal, a drunk local or a drunk tourist has destroyed them. In most other places I know, such ‘structures’ would hardly have survived the night.

There are a lot of swimmers on the rocks, in the sea and under the pines and the camps I passed by are also full to the brim, just like in July. It seems that, in addition to the record-breaking tourist season in August, September will also break a 2019 record when it comes to Croatian coastline tourism. Croatia caught up with Serbia in terms of the percentage of vaccinated citizens (both had 41.5% on Sunday, September 26), but the daily number of infected and dead is much lower. Masks here are worn only by shop assistants and waiters, mostly on their chins.

Direct Media hosted their traditional dinner at the Sidro restaurant on the last evening of the festival. This year, Direct Media, one of the largest regional marketing and media agencies, is also marking its 20th anniversary, so there are even more reasons to celebrate. Rovinj seems to have annulled all divisions and media hunts, so at the dinner, even those people who had often spoken badly about Direct Media in the past, are now enjoying themselves while drinking Malvasia wine and feasting on cod. But that is probably what the charm of this Istrian town does to you, where everyone who comes from Serbia behaves normally. Once they return to their offices and newsrooms tomorrow, everything will go back to old ways, until next September, the new Weekend Media Festival and the new bottle Malvasia, when, while listening to Bajaga singing about the blue sapphire, longing and sorrow, we will again wonder who pitted us against each other.