Aksentije and Janoš’s friendship as a guidepost

The castle, currently the largest in Vojvodina, was built in 1857 by lord László Karácsonyi. Today, it has the status of a “cultural monument of great importance”. When you see what condition it is in presently, you start to wonder what cultural monuments that are not “of great importance” look like in our country. As the pastor told us, there was another castle in Beodra, at the entrance to the village, even bigger and more beautiful than this one. It was built by László’s brother and demolished after the Second World War.

László’s great-grandson, Aladár Karácsonyi abandoned the smaller castle just before the end of the First World War. In late 1918, during the disintegration of the Austro-Hungarian Empire, a mob stormed the castle, looted it and threw out the inventory. The following year, 1919, Mikhail Rodzianko, a Russian immigrant and former president of the Russian Duma who lived there until he died in 1924, moved into the castle. In 1938, the castle was sold to the municipality of Belgrade, which used it as a primary school. During the Second World War, when Banat County was under German occupation, a mental hospital was located here. After the war, it was a home for the children of fallen soldiers, after which it served as “a home for young boisterous girls” (whatever that means), and since 1960, it housed the Miloš Popov primary school, as evidenced by drawings of children’s motifs on the wall next to the central staircase. In 1980, according to someone’s nutty idea, the chemical company, Hinnom moved its offices into the castle and remained there until 2000, when it went bankrupt. After that, the Karácsonyi castle serves no purpose and is in bad condition. We found the remains of the chemical company in most of the rooms – large chemical tanks, scattered equipment and documentation, and a freight elevator which was installed at the back. It is interesting to note that the director’s office has a perfectly renovated wooden ceiling, with a varnish that is still glossy to this day, i.e. twenty years since the castle was abandoned.

Locals say negotiations are underway with a Turkish company that will reportedly transform it into a luxury spa hotel.

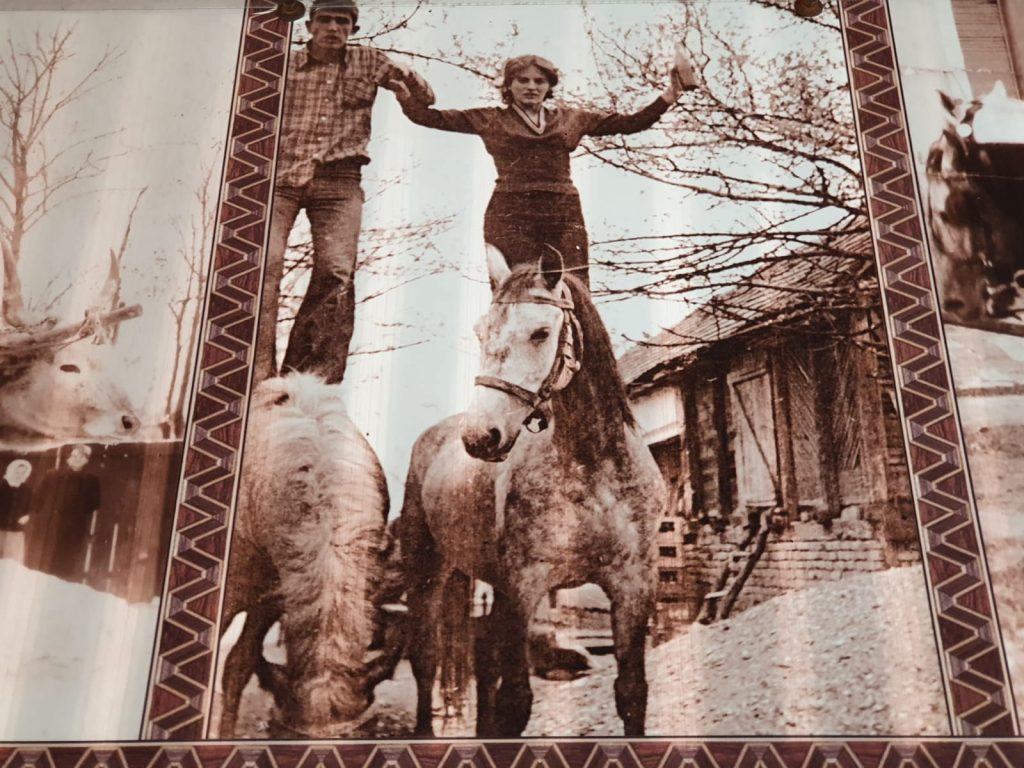

The Kotarka Museum is right across the castle. The museum is housed in the Karácsonyi family’s grain warehouse. “Bogdan Karácsonyi bought the large estate of Beodra, today part of Novo Miloševo, from the Viennese court in 1781, for 105,000 forints,” says Iskra, the museum’s curator, who kindly shows us the exhibits and warns us of freshly painted thresholds and doorframes. Iskra looks and talks as if she works in a New York museum and not in a museum in a forgotten town in Banat. She shows us a large stone sculpture of a lion that was located at the entrance to the other, demolished castle of the Karácsonyi family. The museum’s collection currently numbers over 4,500 exhibits, and I am especially attracted to the collection of black-and-white photographs depicting life in the village fifty or more years ago. In one of the pictures – a village vet, who is now retired, as they told me – is standing on the back of a horse.

Hanging on the wall, I recognize a copy of an interesting oil painting that I saw at the exhibition European Phenomena at the Matica Srpska Gallery in Novi Sad. The painting depicts two priests, Orthodox and Catholic, shaking hands and posing for the painter.

There is an interesting story about the painting’s protagonists. Janoš Boćan was a parish priest with the longest tenure in the Catholic Church in Belgrade. During his service (1828 – 1878), a new church was built and it is considered to be one of the most important periods in the two-century-long-life of the parish. His close friendship with the Orthodox priest, Aksentije Joanović, the grandfather of Dr Đorđe Joanović (one of the founders of the Medical Faculty in Belgrade), lasted for several decades. Priest Boćan had lunch every day at the corner inn, near the Catholic Church, and when he was widowed, the elderly Joanović also had lunch there regularly. On one occasion, the painter Đorđe Pecić, a student of Konstantin Danilo, happened to be at the inn, so the two great friends were immortalized on a canvas. On the back of this oil painting, it says that the work was completed on February 24, 1878, when Boćan died, while Joanović died the following year. The friendship and brotherhood of Orthodox and Catholic priests from the middle of the turbulent 19th century, who were deservedly commemorated at the European Phenomena exhibition, can be an important ‘guidepost’ for their contemporaries at the beginning of the 21st century.

Walking through the park in the village’s centre, on our way to the famous Žeravica Museum, we pass a monument that is erected in honour of the locals who died as soldiers on the Salonica front, as well as those who lost their lives as Partisans in the Second World War, some 25 years later. Several decapitated pedestals clearly show that some people care more about earning money from scrap metal than appreciate history and tradition. I was never a fan of tractors and other agricultural machinery, perhaps because I drove and repaired them until I was 19 (or rather before I served a mandatory military service at the Yugoslav People’s Army and later moved to Novi Sad) with my father, who was a farmer and had three tractors, two combines and a large number of auxiliary machines. My father had quite odd methods, for lack of a better word, when it came to raising us and work. However, when I entered the yard of the Žeravica Museum and a few minutes later the museum itself, I was sorry that my father was not alive to see this.

I have been to similar museums from Manchester to Venice but the museum collection of this village in Banat is so abundant and well-arranged that is fitting of any big city in the world. Touring this museum should be mandatory for all school children in Vojvodina.

It all started in the late 1970s, when Milivoj Žeravica (1931-2009) had an idea to buy a Fordson 10-20 HP tractor from 1924, the one just like his father Milorad (1909-1968) had. This tractor was the first of its kind in the village and Milivoj grew up with it. Having a tractor in the countryside was a real rarity and a kind of attraction at that time. Quite by accident, he learned from a friend that there was such a tractor for sale in the vicinity of Kragujevac. He went to see it and was surprised when he found several similar tractors from that time there. At that moment, he came up with the idea to buy them all and thus somehow save them from becoming obsolete in this part of the world.

Milivoj Žeravica was the founder of the current standing exhibition at the museum, while his son, Čedomir, completed it. The exhibited tractors came from all over Serbia. The collection was open to the public in 1991 in a purpose-built facility. The oldest preserved tractor in Serbia and the region, the American Hart-Parr 30″ from 1920, occupied the central place in the collection. Then there are numerous specimens from the interwar and post-war period produced in European and American factories. Furthermore, the museum has a segment with an ethnic exhibition with old crafts, as well as a larger collection of old radios and cameras.

The Popov’s family house is next door to the Žeravica Museum. This is a childhood home of Duško Popov, a man whom Ian Fleming based his famous character on – the well-known secret agent 007. Duško Popov was born in Titel in 1912, by coincidence, while his origins are from Karlovo, i.e. today’s Novo Miloševo. As we fight the wind on the way back to Novi Bečej, I am contemplating how Novo Miloševo could become the Karlovy Vary of Vojvodina. The village has so many attractions and so much potential that it could make a living from tourism and employ the locals from the surrounding villages and towns. If the Karácsonyi castle does get renovated and transformed into a spa hotel, if a James Bond theme park was created, with the Žeravica Museum, the Kotarka Museum and the village churches, Novo Miloševo could set an example of how the glorious past is put in the function of a happier future.