In Svaneti, which was controlled by mafia gangs since the collapse of the USSR in 1991 until only 15 years ago, tourism has started to develop only recently – roads are being built, hotels and ski resorts are being opened, while the airport building in Mestia, named after a medieval Georgian queen Tamar, has made it to the BBC’s list of the 10 most beautiful airport buildings in the world.

Chuburhindzhi, the administrative crossing between Georgia and its breakaway province of Abkhazia, resembling our Jarinje, but with no barricades and stickers on license plates… Old women, dressed in black, are pulling bags and the policeman warns us not to take photos.

Abkhazia declared its independence from Georgia after the 1992-1993 war. To date, Russia, Nicaragua, Venezuela and Nauru, as well as South Ossetia and Transnistria, have recognized it as the independent Republic of Abkhazia.

International organizations such as the UN, the European Commission, the OSCE, the NATO, the World Trade Organization, the Council of Europe and most sovereign states recognize Abkhazia as part of Georgia.

A van carries a group of media representatives from Serbia who came to Georgia to see a natural beauty and abundant cultural heritage of this ancient European civilization, all before the imminent establishment of a direct flight to Belgrade.

Our driver is a refugee from Abkhazia, who was only a child when, in 1993, his family had to leave their house and flee to the south.

As he is driving along the Enguri Valley, on a road reminiscent of the ones in the Morača Canyon, the scenery around us is changing and at times, resembles the Indian Summer in New England. A few minutes later it looks like a postcard from Switzerland or a picture on a Milka chocolate wrapping paper, featuring a cow grazing on a green slope while in the distance we can see the white peak of the Ushba Mountain (standing at 4,710 metres altitude).

It was already dark when we arrived in Mestia, the capital of the mountainous region of Svaneti. Everything is reminiscent of any other mountain resort in Europe, except that there are dozens of stray dogs on the streets here. As in the rest of Georgia, stray dogs are all chipped, neutered and very tame, constantly wrapping themselves around your legs and wanting to cuddle.

To stretch our legs a little after a five-hour drive from Kutaisi, we decided to take an evening tour of the famous Svaneti Towers. The story behind these towers begins in the 8th century, when due to a foreign invasion, but also conflicts between family clans that often ended in blood feuds, stone towers were built next to every house in the Upper Svaneti region. There used to be 280 of them, but only 175 remain in the whole region.

The Svaneti Towers are unusually reminiscent of the ones in San Gimignano in Tuscany that we saw in 2009. Today, the Svaneti Towers are included in the list of the UNESCO World Heritage Sites and although the streets around them are steep and rocky, they are beautifully lit which made our night walk quite enjoyable.

Even in the dark streets of Mestia, you do not feel threatened by locals whose shadows appear every now and then on the illuminated walls of stone houses and towers. “There is almost no crime in this area. People here know that every incident would destroy the tourism they live off, so it never occurs to anyone to do anything bad to foreigners,” Tina, a girl of small stature, with smart eyes, tells us. She was assigned to us as a tour guide by the Georgian Tourist Board during our seven-day stay.

The next day, after breakfast, seated in two SUVs, we set off for Ushguli, a community of four villages (Zhibian, Chvibiani, Chazhashi and Murqmeli) high in the mountains, under the Shar summit (5,193 metres). Ushguli in the local language of the Svan people means “braveheart”. Parallels with the Scottish Highlanders draw themselves.

The 45-kilometre-long road to Ushguli leads through sharp, mostly completely unprotected mountain passes in several places, intersected by torrents.

The driver of our SUV, a local in the late sixties, plays a mix of local music and in skilful slalom, bypasses the cows that walk the road almost as if we were in India.

Today, Ushguli has a population of about 250, who work in agriculture and tourism. There are several hotels (one is called “NATO”), a couple of cafes and households that rent horses and hiking equipment for tourists. Four villages share one school and five churches – the most famous of which is Lamaria (Church of the Mother of God).

The entire region was ruled by local mafia gangs since the collapse of the USSR until only15 years ago. After the arrest of their leaders, tourism started to develop in the valley began, as did the construction of roads and airports.

We arrive in front of the Church of Lamaria, from the 9th century, which is dedicated to the Mother of God, but its name derives from the ancient cult of the Svani people, who respected the pagan goddess of fertility.

According to local legend, the Church of Lamaria was the scene of the murder of Puta Dackhelani a member of the Dadeshkeliani family of aristocrats, who tried to impose himself as a feudal lord on the local highlanders. The locals of Ushguli allegedly invited him to a feast to come to an agreement, got him drunk and then executed him in a way similar to the one described in Agatha Christie’s “Murder on the Orient Express”. Namely, the representative of each of the families in the village pulled the rope that was tied to the musket which killed the drunk and deranged guest. In this way, they shared the responsibility and avoided blood feuds against one individual family.

They say that Puta’s shirt is still kept in the church. Next to it, there are a large number of icons, manuscripts and crosses, all of which were catalogued by the famous Georgian historian Ekvtime Takaishvili during his visit to Svaneti.

The cemetery in Ushguli is made of plots, bordered by wrought iron fences, each one containing the graves of one family. After the harsh winter of 1981, which caused a lot of problems for the inhabitants of the four villages, the USSR authorities decided to displace about half of the population to the steppe part of Georgia. It is not difficult to imagine what it was like for the Highlanders when they were transferred from 2,000-metres-altitude to the dry steppes. Some of them returned to Ushgura after 1990, and some remained to live in the steppes. The real reason for this relocation was the fear that the disobedient inhabitants of this part of Georgia would rebel, as well as that the displacement of certain ethnic groups was the common practice of the Soviet authorities.

The film “Dede” (“The Mother”) from 2017, directed by Mariam Khatchvani, is being advertised in several places in Ushguli. The film, whose director and most of the actors come from the four villages, won a special award at the Karlovy Vary Festival. Stephen Dalton of The Hollywood Reporter wrote in his review of the film: “Feminism meets fatalism in this beautiful Georgian melodrama!” This film is screened at a cinema in Ushguli, but also at the cinema in Mestia, where it is showcased (to tourists) several times a day.

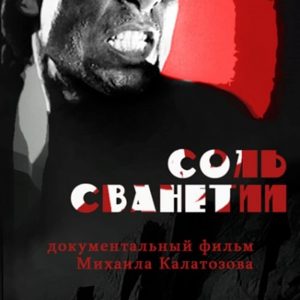

Another film that celebrates this region is the Soviet silent film “Salt for Svaneti” from 1930. It showcases the life in Svaneti, as the backward and inaccessible part of Georgia. The film puts special emphasis on the chronic lack of salt for both people and cattle, with the latter being allowed to “lick the sweat from people and drink urine” to ensure sufficient intake of salt.

The film was made for propaganda purposes in order to glorify the project of modernization of the USSR via its First Five-Year Plan. Despite that, the film was criticized because it highlighted the backwardness and primitiveness of the population in this area. The Svani later complained that the film director, Mikhail Kalatozov, invented some customs and details from their lives in order to portray them as “exotic” as possible. Because of this and his next film “The Nail in a Boot”, Kalatozov fell out of favour with the Stalinist regime.

He continued to direct his war drama “Cranes Fly” from 1957, after Stalin’s death, which was the first significant deviation from the propagandistic depiction of events in the Second World War. Kalatozov is also important as the author of the Cuban film “I, Cuba”, which featured significant technical innovations in 1960s filmmaking. His son Georgi Kalatozishvili and grandson Mikheil Kalatozishvili are also renowned filmmakers.

Moving on… One of the ancient houses in the village was transformed into a small museum where we had the opportunity to see how families and cattle slept in the same room, which was not uncommon in our mountainous areas as well. The heat “produced” by cows, goats and sheep was not wasted, especially in the winter months. We also found the swastika motif in several places.

In the yard we pass by, a seventy-year-old woman is chopping wood. I jump to her aid and she happily hands me a big axe but refuses to be photographed. Tina tells us how tourists are often confused by the frowning faces of the locals who rarely smile. She explains that they are simply mountaineers who have been taught not to show their emotions, and only recently, since tourism started to bring them more money, they are known for giving an odd smile or two.

Exhausted by an almost two-hour walk through the villages during which we tried to avoid the cow dung that littered almost all the cobbled streets of Ushguli, we arrive at the small hotel called Villa Lileo (Lileo is the name of a Svaneti song dedicated to the Sun). Here, the hostess shows us how to knead and bake small loaves of bread, after which we enjoy a tasty mountain meal.

On the way back to Mestia, we are stopped by road works (yes, the road are being paved, not asphalted). As we wait, we watch one of the workers level the holes in the fresh concrete made by the ubiquitous cows passing by.

Mikhail Vissarionovich Khergiani (1932-1969) was a Georgian alpinist, seven-time USSR champion who was nicknamed “Tiger from the Rock” and was awarded the Special Order of Sport of the Soviet Union in 1963.

His birth house in Mestia was transformed into a beautifully decorated museum in 1981. The house also features a tower, the top of which we climbed with the help of several ladders and through the opening on the roof enjoyed a spectacular view of the other towers in Mestia. In front of the house, there were several locals dressed in traditional Caucasian costumes. They were extras in a movie that was being shot there. The local curator told us about Khergiani with such zeal so much so that we were so invested in listening about his life. Khergiani’s uncle was also an alpinist, so little Mikhail started climbing mountains in his early childhood.

After great successes in the USSR, Mikhail joined the British expedition to Mount Everest in 1953 at the invitation of Baron John Hunt. The news of the expedition’s success arrived in London on June 2, the morning before the coronation of Queen Elizabeth II. In the summer of 1969, in the Italian Alps, a fallen stone cut his climbing rope. As he did not have a spare rope, he fell from a height of 600 metres and died.

From the top of the tower in Khergiani’s house, I saw an unusual building. It is the building that houses one of the highest airports in Europe – Queen Tamar Airport. The building was designed and built in 2010 by German architect Jürgen Mayer Hermann and his company, J. Mayer H. and Partners. The BBC included it on the list of the 10 most beautiful airport buildings in the world. The design of this building, spanning 250 square metres, is an homage to traditional Svanetian architecture which features towers next to houses. It is located at 1,467-metres-altitude and is named after Queen Tamar from the 12th century (who is called “king” in Georgia because in their language the ruler is called “king” regardless of gender and “queen” is the king’s wife). Until the pandemic, the small airport served 9,000 passengers a year. The only airliner that uses this airport is Vanilla Sky, which L-410 aircraft take off and land only when the weather allows.

Occasionally, private planes, owned by wealthy people from all over the world, use this runway, which is only 1,200 metres long, as they are starting to discover the natural beauty of this part of the Caucasus.

We leave Mestia at dawn and on our way to Kutaisi, we stop at Chateau Chikovani, a building that is a cross between a castle, a winery and a restaurant. The heir of a family, who dates back to the mid-17th century, tells us about a history rife with turmoil from the time from the Kingdom of Georgia through the Russian Empire and the USSR to the newly independent Georgia. He has a big family tree hung on the wall which shows that his great-grandfather Dmitry had 16 children with one wife while he has only one son. He complains about a shortage of workers and reminds me of one of the Serbian winemakers. His son was born in 1991, lives in Kutaisi and cares little for his father’s business and family tree.