A castle saved by an apple on Sofija Dundjerski’s head

Milan, who has been working here as a security guard for 35 years, showed Matija Kovač, the provincial deputy from Novi Bečej, and me the basement of the house where the other attraction of this castle is located – a 100-year-old bowling alley, a real rarity in this area. There is a bowling ball in the alley and until recently, there were original skittles here, says Milan, but someone stole them. Many local films and series were shot in and around the castle, including “Jesen Stiže Dunjo Moja”, directed by Ljubiša Samardžić.

A potholed field road leads us to Sokolac Castle near Novi Bečej, one of the attractions in this small town in Banat County, which I did not manage to visit during my bicycle tour last summer. The castle, which at that time was called Veliki Salaš, together with auxiliary buildings and 3,997 acres of land, was inherited by Emilija Ivanović, nee Dundjerski, the daughter of Lazar Dundjerski. After the war, the property with a beautiful park was nationalized and was given to the Sokolac agricultural estate (people say that the estate was named after the horse called Sokol), and after several unsuccessful privatizations, it is currently under the jurisdiction of the bankruptcy trustee.

Although closed to the public and neglected, Sokolac is today in better condition than most similar facilities in Vojvodina. The roof is intact, the gutters are in good condition, all the tiled stoves have been preserved (each was fired from the hallway so that coal and wood would not be brought into the rooms), as have some pieces of period furniture, tiles and parquet floor. The castle also hides two real attractions. The first room is Emilija’s sister Lenka Dundjerski and features her portrait painted by Uroš Predić. Above the bed in which Lenka, the big love of Laza Kostić, slept when she came to visit her sister, there is a mysterious portrait of her.

Milan, who has been working here as a security guard for 35 years, showed Matija Kovač, the provincial deputy from Novi Bečej, and me the basement of the house where the other attraction of this castle is located – a 100-year-old bowling alley, a real rarity in this area. There is a bowling ball in the alley and until recently, there were original skittles here, says Milan, but someone stole them. Many local films and series were shot in and around the castle, including “Jesen Stiže Dunjo Moja”, directed by Ljubiša Samardžić. As part of the national project called “Castles of Serbia – Protection of Cultural Heritage”, I believe that this pearl of architecture and significant historical and cultural heritage will once again shine in full splendour.

Žitni Magacin (Granary) is the next attraction that is not that known in Novi Bečej. A road leads us to a dam near the Tisza River and a shepherd with a flock of sheep who cuts us off. We exchange a couple of sentences, I tell him we are “colleagues”, and he tells me, in a strong Hungarian accent, that he has 80 sheep. Immediately after that, he runs after one of them heading towards the road.

The granary in Novi Bečej was built between 1778 and 1780 next to the quay, at the former mouth of Mali Begej, which, at that time, was a tributary of the Tisza River, right on the border which separated Vranjevo from Novi Bečej, also known as the Turkish Bečej. The original function of the granary was storing wheat and sunflower. Today, the warehouse is not in function, it has not been preserved and is being eroded by the ravages of time. This cultural monument is one of the oldest preserved buildings of this type in Vojvodina and Serbia. Following the Decree of the Government of the Republic of Serbia, adopted in 2001, Žitni Magacin in Novi Bečej was declared a cultural monument.

Matija unlocks the door and we enter an incredible space where our focus immediately shifts to the imposing beams made of solid wood from Transylvania that intertwine on all three floors. We climb the dilapidated stairs to the attic, carefully walk along the joints of the boards and talk about how one day this could be a gastronomic market where producers from all over Vojvodina would present their specialties.

In 1907, an eligible bachelor called Vladimir Glavaš apparently had a lot of problems with the opposite sex considering that he had bequeathed his house to the Serbian Orthodox Church on the condition that a woman should not step foot into it for 100 years.The Glavaš House Memorial Museum is located between the Orthodox and Catholic churches, in the ambience of the old town centre in Vranjevo, which is now part of Novi Bečej. The building was erected in the first decades of the 19th century and belonged to the respectable and wealthy Glavaš family.

Vladimir Glavaš was born in 1834 in a wealthy family from Vranjevo, to father Pavel and mother Persida, nee Čorbakov, whose ancestors were Serbian border guards of the Potisko-Pomorška military frontier who did not go to tsarist Russia after its de-militarization in 1751, but founded Franjevo (Vranjevo), which for a century and a half was part of the Veliko Kikinda district bearing special imperial privileges. Vranjevo became one of the main centres of the export of the grain from Banat (from the aforementioned Žitni Magacin), and many people from Vranjevo quickly became rich, including the Glavaš family.

Vladimir, a doctor of law, who studied in Poszony and Prague, bequeathed the house and his other property to the Serbian Orthodox Church in the Municipality of Vranjevo in 1907, two years before his death, with the above-mentioned unusual condition. One hundred years later, the building was in a very dilapidated condition (perhaps precisely because there was no female hand to maintain it) and was taken over by the Municipality of Novi Bečej which began to renovate it. Today, it houses a memorial museum which is in excellent condition.

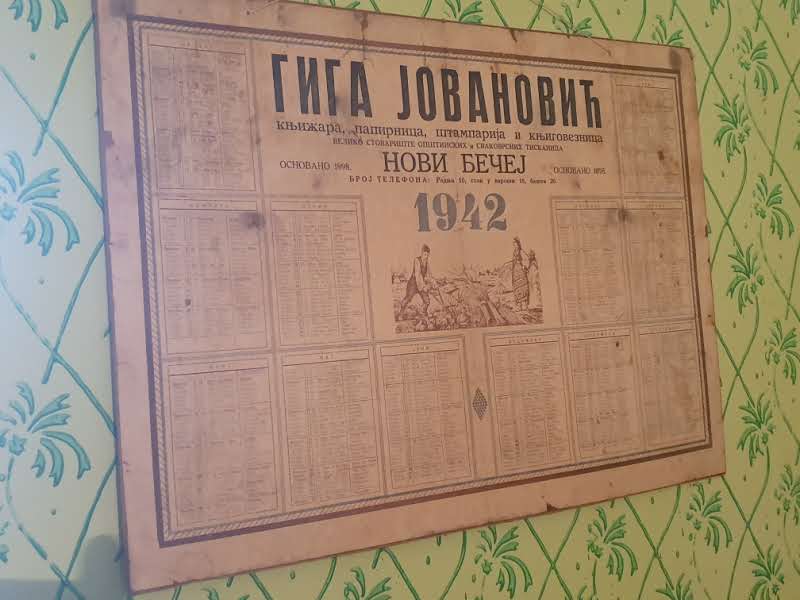

Janos, the curator of the memorial house, played an excellent host to us and took us from room to room to a spacious yard and an auxiliary building in which various old crafts and agricultural machines that were once used are presented. One of the photos shows the welcome that the Serbian army received in Vranjevo during the liberation in 1918 which feature well-groomed men and women in the most beautiful clothes, holding portraits of King Petar and Regent Aleksandar. There is a very narrow door between the kitchen and the dining room so that the heat and smells from cooking would not bother the family while they enjoyed lunch. At the entrance, there is a wooden tool for removing boots, which Janos says had its own name – “the maid”. In one of the rooms on the wall, there is a 1942 Cyrillic Orthodox calendar which was printed by Giga Jovanović bookstore, paper mill, printing house and bookbinder. Janos tells me how Giga Jovanović, one of the wealthier residents of Novi Bečej, continued working during the German occupation of Banat in the Second World War.

In addition to a large bookstore and a modest printing house founded in 1898, Vladimir Glavaš had a large flower garden at the end of the main street in Novi Bečej, on which a dozen residential buildings were built after World War II, and a farm surrounded by close to thirty acres of land. Until his death, he was the director of the Turkish Bečej Savings Bank, which capital exceeded one million dinars. He was an active member of the society – a long-term president of the Voluntary Fire Brigade in Novi Bečej, head of the Sokol Association Novi Bečej and a prominent member of many other organizations. He was also a regular member of Matica Srpska in Novi Sad. During his life, he built a beautiful tomb, with a tombstone, which is an ornament to Novi Bečej’s Orthodox cemetery. He died in 1944, thus avoiding the humiliation that many wealthy farmers (the so-called kulaks) in Vojvodina experienced after the liberation.

Giga, like many of his other influential contemporaries, had no descendants to take care of the monument and its maintenance. The basement of the Glavaš House stores brandy that Janos makes from fruit grown on the estate which we had a glass of. There is also a gate bearing the Star of David that stood at the entrance to the synagogue. On the eve of the Second World War, 220 Jews lived in Novi Bečej, while Isidor Schlesinger was the then president of the Jewish community. The synagogue was located deep behind the gate, surrounded by a metal fence with brick pillars. After the German occupation of Banat in the spring of 1941, the synagogue served as a collection centre, not only for the Jews from Novi Bečej but also for those from the surrounding area. Pursuing their anti-Semitic policy, the Nazis deported them by barge to Belgrade and Pančevo and killed almost every single one of them. Filip M. Polak was the last rabbi of Novi Bečej.

As not a single Jew remained in the town, and considering that, during the war, the synagogue was very dilapidated, the municipal authorities decided to demolish it in 1947. Today, in its place, stands a privately-owned house at 16, Žarka Zrenjanina Street, as a testimony that there used to be a Jewish synagogue here of which only the Star of David remained, attached to the lower part of the metal gate, hidden in the yard of the Glavaš House.