Das Licht von Kairo and other stories

By Žikica Milošević

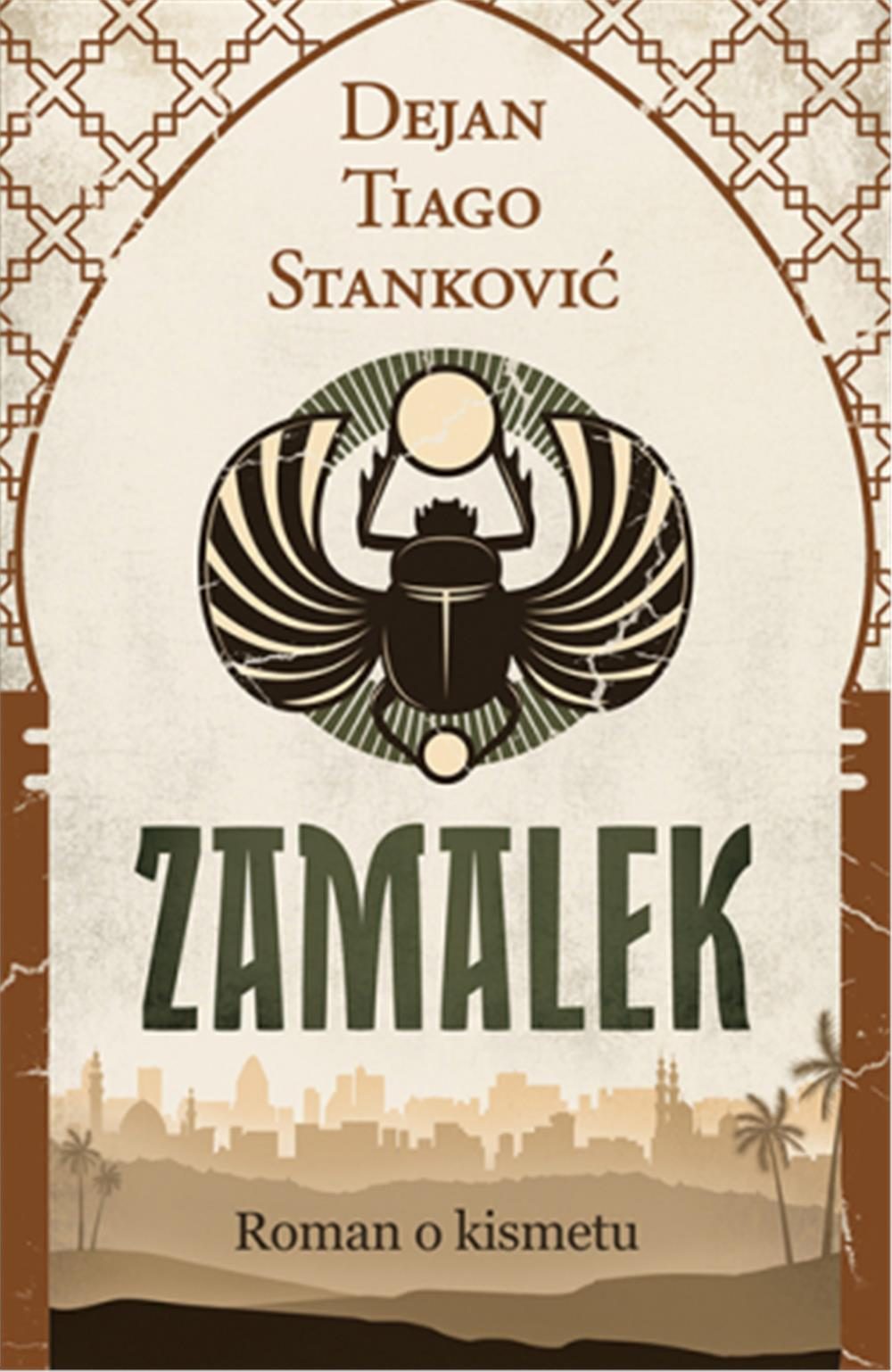

From a translator and a bridge between Serbian and Portuguese culture, Dejan Tiago Stanković slowly began to grow into a hit writer. His latest novel, Zamalek, proved to be a bestseller, and it speaks, unlike his earlier works about Portugal, about the vibrant megalopolis – Cairo. Many compare him to Darrell, Kipling and Mahfouz but he likes it the best when people say that he was influenced by the best writers around whose works he translated – Andrić and Saramago. In this interview, Dejan tells us what led to his “finest hour”.

- Where did the love for the Portuguese language and Portugal come from, first of all? Why did you choose Lisbon as your home?

It came by accident. Shortly before the war, since I graduated in architecture and went to London, to finish my education without going to school, since London was a very exciting place. I met a girl, a Portuguese one, we had a child, we didn’t feel like staying in London anymore, and returned to Portugal to be close to her family. I’ve been living here for almost 25 years and 15 years in Lisbon.

2. Why did you choose Tiago as your middle name?

I wasn’t aware of my problem until I saw Google for the first time, and as usual, I googled my name. I realized that the curse of the name Dejan Stanković has something to do with football. I had to come up with an artistic name. Another problem from that time was that when we were at border crossings I was often asked why my children didn’t have the same last name. They are Portuguese from their mother’s side, and according to their custom, they have two surnames, their mother’s and father’s, i.e. Tiago-Stanković. And my last name is only Stanković. That’s why I took this name – because it is unique and people can confuse my name only with those of my direct descendants.

I’m always happy when people tell me that my work resembles that of good writers. I like it the most when they tell me that they can see that I was influenced by the writers whose books I translated.

3. Translators are bridges between cultures. You translated Saramago into Serbian and Andrić into Portuguese. How exciting was that challenge for you?

Writers who write well and meticulously are easily translated. Translating is like rewriting someone’s book but in a different language. When your translation is bad, the writer usually wrote something sloppy. So, for me, translating always went well, because the writers had written well. By translating the works of the best writers, Nobel laureates and classics, I learned the craft.

4. After the first two books about Lisbon and Estoril, places you got to know by living in them, you jumped over to Cairo and your novel “Zamalek” caused a lot of commotion among readers and became a real literary hit. Some people call this novel a twisted travelogue of Cairo and say that it resembles a mixture of Kipling’s, Darrell’s and Mahfouz’s books, as well as films by Wenders and Ivory. It sounds exciting to have a bestseller about an exotic destination. How did the book come about?

I’m always happy when people tell me that my work resembles that of good writers. I like it the most when they tell me that they can see that I was influenced by the writers whose books I translated – Andrić, Mihajlović and Saramago. If my work resembles that of other writers, it is a pure coincidence. I’ve never read any other books so meticulously that they would leave an imprint on me. By the way, I am an architect by education, I loved urbanism the most in my studies, and I love cities because of the variety of people that live in them. The book about a city I don’t know, Cairo, was created because my dear friend Arna was in the Croatian diplomatic service in Cairo, so I went to stay with them for a few weeks a year during their entire tenure. We stayed in Zamalek, I hung out with ex-pats, diplomats, Serbian emigrants and neighbours – Zamalek is based on their stories. It lasted for four years. There I heard a story about the posthumous adventures of one of our emigrants, how he suffered and about kismet. However, a novel about kismet could not be understood and it would not be that interesting to write what happened to someone after their death without having prior knowledge of Cairo. That is why I made chapters from the footnotes that were needed to understanding the book. So, I can see why they are jokingly calling the book ‘a travelogue’.

5. How much has architecture, the “construction profession,” helped you “build” your books?

I don’t build books, I weave them. Like making patchwork… I assemble them. I weave the pieces, arrange them and assemble them into a big picture. That’s why my chapters are short. I learned that writing a diary on Facebook. By the way, “Zamalek” became a literary hit because my audience, which follows me on Facebook, and there are 20K people there, read my articles every day. I’ve been doing this for almost ten years and I’ve been reading a lot but during the lockdown, I saw that a rather strong audience was getting bored, so I tried to entertain them. There I learned that nowadays only short chapters hold attention and that we must be quick to attract and maintain curiosity because the modern reader has stimuli from all sides and cannot focus that easily. You should first attract their attention, but unobtrusively, then they start liking you, at a certain point you even annoy them and then they fall in love with you all over again. It’s a long process – for one writer to get to the established audience, and today most people work on social media.

6. All books are connected by an ex-pat theme – both “Estoril” and “Zamalek”.

My topic is emigrants because I have been a semi-nomad for decades and I like that. People who have changed climate and culture are interesting – they are like transplanted plants, and they prove how important resourcefulness is.

7. What should we do next after the “old normal” returns?

By the way, I have had “Estoril” translated into English and I got quite a big publisher. I did well. I am a recipient of a renowned award in Serbia and also got a sweet award from fellow writers of historical novels in English as “the discovery of the year”. I have, of course, a Portuguese version, as well as a Spanish, Russian and Bulgarian one. “Zamalek” is being translated into English. I guess that novel will make some waves too.