Renowned economist and Prime Minister Narendra Modi’s Economic Advisory Council chairman Bibek Debroy explains how India is on the right path to become a USD 5-trillion economy

Over the past few years, India has often been tagged as one of the fastest growing world economies, a scenario that looks even brighter when pitted against the global economic slowdown.

The Indian government has announced an aspirational target of making India a USD 5 trillion economy by 2024-25. While some have been calling this unachievable, most ignore the massive size of the Indian economy while making predictions. Even if it grows at a slower pace, India’s contribution to the world economy will be larger due to its volumes.

India has already embraced new paradigms such as the sharing economy with aggregator platforms displacing conventional businesses. Government has harnessed new technologies to enable direct benefit transfers and financial inclusion on a scale never imagined before.” Nirmala Sitharaman, Minister of Finance of India

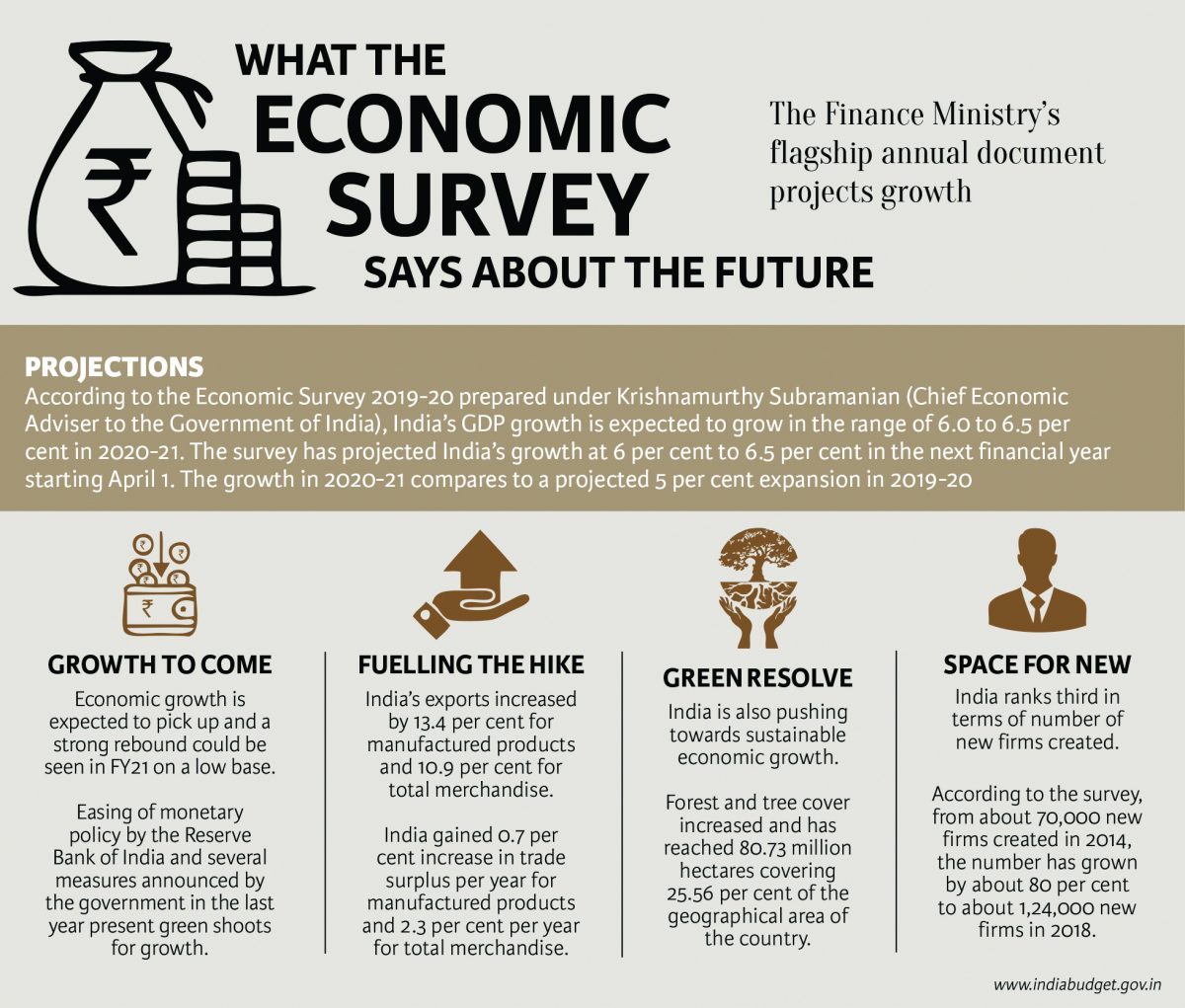

A GDP growth rate of eight per cent is required to meet the USD 5 trillion target and the government’s initiatives of efficient public expenditure, efficient land, labor and capital markets and stimulating productivity and entrepreneurship are meant to trigger this. Needless to say that there is enough slack in Indian states to deliver an eight per cent growth. A higher GDP is not just a number. It translates into higher incomes, more employment, better living conditions, lower poverty and improved socioeconomic indicators. While a slowdown has been witnessed in the last quarter, India’s monetary and fiscal stimulus has already begun to kick in and will show soon. Looking at the status, one can assume that in the financial year 2019-20, India will have a real GDP growth of around five per cent. Next year, in 2020-21, the growth rate will increase to at least six per cent and inch towards another half percent more.

One of the successes of macroeconomic management since 2014 has been control of inflation. Inflation is a regressive tax. It hurts the poor relatively more than it hurts the relatively rich. Six per cent real growth and four per cent inflation yield 10 per cent nominal growth, while six per cent real growth and nine per cent inflation yield 15 per cent nominal growth. While 15 per cent nominal growth may make one feel better than a 10 per cent nominal growth, but the latter, with lower inflation, is preferable.

I think while we have seen temporary pains, with the leadership that the finance minister provided, we’re just going to get out of it. External turbulence (has) hit us, but I am very optimistic. Mukesh Ambani Chairman and Mg. Director, Reliance Industries

However, the aim is to move India to a higher growth trajectory. Since 2014, and the policies of the second Narendra Modi government are a logical continuation of the first, the building blocks are being put in place to ensure precisely that. First, the external environment is unkind, global uncertainty affects India’s export and growth prospects too. Not too many countries are likely to grow at six per cent. Second, there is plenty of internal slack in the system and endogenous sources of growth. Historically, India’s governance has been excessively centralized. Since 2014, there has been institutional change, making governance more decentralized. An example of this is the way GST (Goods and Services Tax) Council functions. Decentralized governance is more than mere fiscal devolution, though this too has occurred through recommendations of 14th Finance Commission. (Recommendations of 15th Finance Commission are expected in 2020.) Third, inclusion has to be interpreted in the sense of public provisioning of physical and social infrastructure. Dashboards, available in the public domain, illustrate improvements in availability of roads (and other forms of transport), electricity, gas connections, toilets, sanitation, housing, schools (and higher education), skills, medical treatment, insurance, pensions, bank accounts and credit. The veracity of what dashboards show has been confirmed through third party validation. This improvement is especially evident in rural India. That is the reason the UNDP’s recent Human Development Report highlights sharp drop in multi-dimensional poverty. Inclusion is also about subsidizing the deprived. This is now done through decentralized identification (a census, not a survey), using what is known as SECC (Socio- Economic Caste Census). This survey is used to identify beneficiaries, both for Union and state-level schemes, eliminating leakage and multiplicity. Subsidies are now channeled into bank accounts and linked to Aadhaar (Aadhaar is an identification number issued by the Unique Identification Authority of India to every resident of the country). Productivity gains from such inclusion initiatives and empowerment cannot be immediately quantified in economic terms. However, they are palpable (and confirmed anecdotally, such as in the switch from firewood to LPG, or provision of toilets, or Mudra loans) and will enable India to reap the demographic dividend contribution to growth.

Fourth, that inclusion and economic empowerment agenda is against the background of improving both the citizen’s ease of living and the entrepreneur’s ease of doing business. An entrepreneur is not necessarily a corporate entrepreneur. Nor is ease of doing business only about World Bank’s ease of doing business indicators, where too, India’s rank has improved. The ease of doing business initiative under the Department of Industrial Policy and Promotion (DIPP) or the Department for Promotion of Industry and Internal Trade, has improved the business and investment climate in all states. Modernization of land records and cleaner titles is also work in progress. Investment figures (including FDI) show improvements. Fifth, the institutional cleaning up is bound to have adverse consequences for growth in the short run. Examples of such institutional cleansing are the Real Estate (Regulation and Development) Act, scrutiny of illegal financial transactions, clamping down on shell companies, an insolvency and bankruptcy code and improved tax compliance.

These will lead to immediate growth costs, traded off against efficiency gains in the future. Broadly, India is in the process of making land (and natural resources), labor and capital markets more competitive and efficient, with not just entry, but exit as well. Union government finances have been managed well, with no deviations from the goal of fiscal consolidation. Tax reform is a work in progress and the corporate tax rate has already been reduced. For both direct and indirect taxes, the agenda is simplification and elimination of exemptions, leading to lower compliance costs. Thus, the broad message is that a five per cent GDP in 2019-20 should not lead to gloom and doom; there is a higher growth trajectory in the offing.

The Indian economy has been going through a process of detoxification.The negative impact of disruptions is now over and the economy is expected to see an upside in FY21. Anand Mahindra, Executive Chairman, Mahindra & Mahindra Ltd

Going forward, the real growth should be higher at 6-6.5 per cent in the next financial year. We have focused a lot on rural consumption. Krishnamurthy V Subramanian Chief economic advisor, Government of India

I think while we have seen temporary pains, with the leadership that the finance minister provided, we’re just going to get out of it. External turbulence (has) hit us, but I am very optimistic. Mukesh Ambani Chairman and Mg. Director, Reliance Industries

India has already embraced new paradigms such as the sharing economy with aggregator platforms displacing conventional businesses. Government has harnessed new technologies to enable direct benefit transfers and financial inclusion on a scale never imagined before.” Nirmala Sitharaman, Minister of Finance of India