Across Vojvodina on a bicycle

By Robert Čoban

Trandžament Cemetery in Petrovaradin

During one bicycle ride around Petrovaradin during last year’s state of emergency, I rode up from Kačićeva to Mažuranićeva street, then crossed into Majurska and from there through Tunislava Paunovića street to the highest street in this part of the city – Trandžamentska. At the end of that street, through the bushes and the meadow, you enter the Trandžament Cemetery, which, out of all ‘eternal resting place’ in our town, reminds the most of the Parisian cemetery, Père Lachaise. It’s not that big and you won’t get lost in it as it happened to me when, two years ago, after visiting the rather remote grave of Edith Piaf, my phone battery died and without GPS, it took me an hour to find the exit where I left my bicycle.

“The Military Cemetery on Trandžament has been a final resting place for soldiers since the beginning of the construction of the Petrovaradin Fortress (1692)”

It became a graveyard for all the soldiers who fought in the wider area, no matter which side they were on. Soldiers of the Austrian and Turkish armies, two armies that often fought in this area in the late 17th and early 18th century, are buried in this cemetery. Then there are the revolutionaries from the famous 1848/49 uprising who are also buried here, as well as those who stifled the revolution. In the upper part of the cemetery, there is a monument erected in memory of the fallen soldiers of the 19th Infantry Battalion of the Austrian Empire who died in the revolutionary battles, many of whom were Serbs – 1,229 soldiers and 60 officers in total.

Austro-Hungarian soldiers were buried here (from the time when the agreement on the establishment of the dual Austro-Hungarian monarchy in 1867), as well as the graves of soldiers from the First and the Second World War. Right next to the yards of local houses there is a monument to Russian prisoners of war in the First World War – 96 of them were buried there and the monument was erected by Russian emigrants in 1929. It was restored in 2013 with funds from the Ministry of Defence of the Russian Federation.

Most of the Russian soldiers buried here were, at one time, housed in makeshift camp barracks at the old Novi Sad Railway Station (on the site of today’s Limanska outdoor market) and died as a result of injuries, as well as diseases caused by inadequate living conditions in the camp. Although, today there is practically no memory of the tragically killed Russian prisoners, in the period between the two world wars, people who made the so-called White Emigration, who settled in Novi Sad after the October Revolution, attached special importance to these locations through the activities of the Novi Sad branch of Ruska Matica (cultural and scientific institution of the Russian people). This is evidenced by the fact that there was an initiative to build a Russian memorial church to the Blessed King Alexander I the Unifier on the corner of Futoška and Braće Ribnikar Street, whose crypt would store the remains of 204 Russian prisoners of war who died between 1915 and 1918 in Novi Sad. Although money for the construction of the temple was secured, the outbreak of World War II and later political constellations stopped the implementation of this plan forever.

A particularly interesting part of the Military Cemetery on Trandžament is a plot with 45 identical stone crosses featuring metal plates with engraved names of allied French soldiers who did not die during the battle but died from the epidemic of the Spanish flu in 1918. On November 9, 1918, French soldiers, together with the victorious Serbian army, entered Petrovaradin and Novi Sad through the Belgrade Gate after the withdrawal of Austro-Hungarian troops from the town.

The crosses have a simple shape, and today most of them no longer have metal plates with the names of buried soldiers. However, judging by the plates that are still on the crosses, we can conclude that there were also soldiers of African origin who served as mercenaries within the French army. By perusing through books written by the Novi Sad chronicler Triva Militar, I came across information about two local beauties who fell in love and later married French soldiers from Senegal and Indochina respectively and later went with them to their native countries.

“Judging by the plates that are still on the crosses, we can conclude that there were also soldiers of African origin who served as mercenaries within the French army”

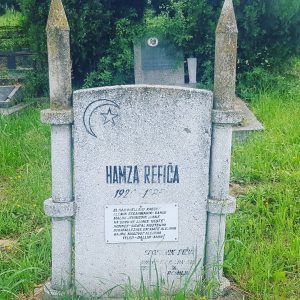

Kristijan Obšust from the Archives of Vojvodina, who is an expert on this topic and wrote the paper called “Historical Cemeteries in Novi Sad as Places of Remembrance”, drew my attention to the fact that there is also a Muslim cemetery that was built without the permission of the city authorities in the 1950s. This practice was interrupted in 1992 when a demarcated burial by denomination was made possible at the Central City Cemetery in Novi Sad, which provided burial places for the deceased Muslims.

As recently announced, Novi Sad will get its Pet Cemetery on the Trandžament too, where owners will bury their beloved dogs and cats. One such monument reads, “Loyalty for loyalty! My good and faithful dog Rita 1964 -19.. ”. As you can see, the year of the pet’s demise has not been stated, so we can assume that the owner did not outlive it.

The cemetery also contains a common grave of partisans who were shot in Vukovar on October 19, 1941, and whose remains were later transferred and buried at this location. The stone tomb in which the remains of nineteen people rest is a memorial and a place of remembrance for the executed members of partisan detachments and local members of Narodnooslobodilačka Vojska (the People’s Liberation Army) that operated in the area of Petrovaradin.

The famous tamburitza player, Janika Balaž (1923-1988), Josip Zebetić (1838-1907), major of the 70th Infantry Regiment of the Austrian Army, and Josip Hanel (1838-1883), the first mayor of Petrovaradin, were also buried in this cemetery.

Bearing all the above in mind, it is not surprising that the names of the dead and gravestone epitaphs are written in Latin, Gothic, Cyrillic, German, Hungarian, Serbian, Russian, Slovak, Czech, Polish, Latin, as well as in the Arabic language.

This huge archaeological and historical treasure is quite neglected and the time has come to begin its restoration since almost everything that was made of marble and iron was stolen and a lot of monuments were destroyed by the ravages of time. Père Lachaise cemetery, from the beginning of this story, which also has a map of the cemetery with designated celebrities, is not the only such tourist attraction in Europe and the world. Trandžament Cemetery, an important place of a culture of remembrance of the past few centuries, deserves a similar status.