Serbia lags behind while corruption spreads, inflation soars, and the workforce flees

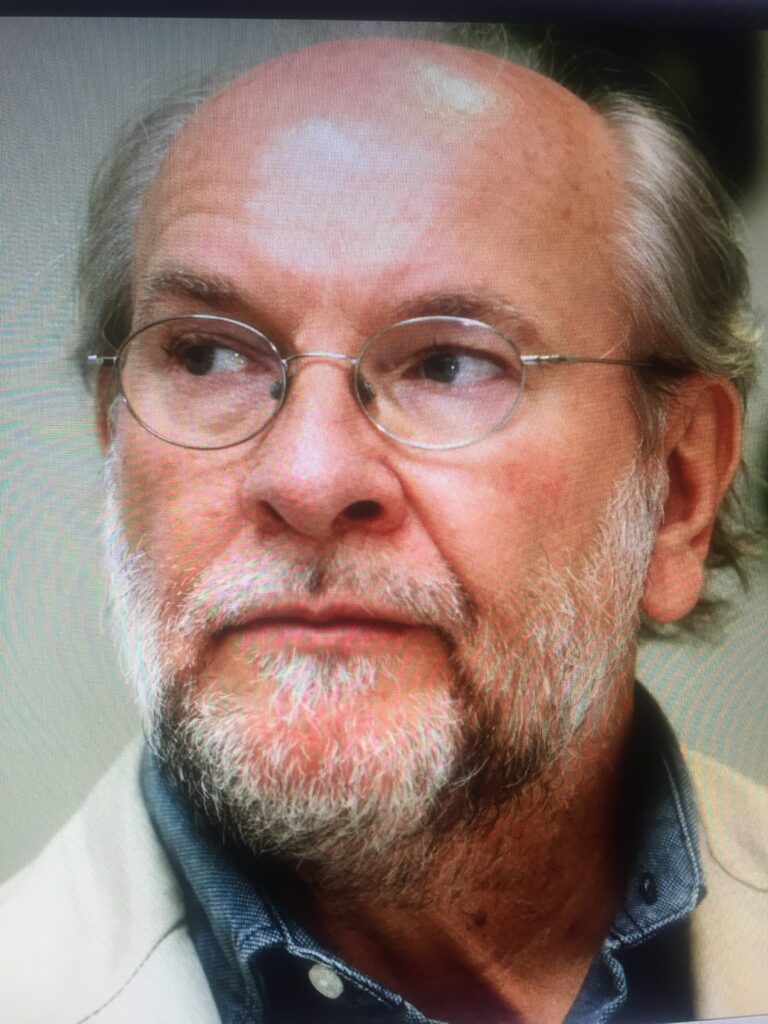

Miša Brkić, a renowned economic journalist, sharply analyses Serbia’s current economic and business landscape. From entrenched corruption and inflationary pressure to the challenges of EU integration and workforce emigration, he dissects the key factors shaping the country’s stagnation. In this interview, Brkić explains why Serbia struggles to move forward, how political decisions impact the economy, and what it would take to break free from the cycle of inefficiency and missed opportunities.

Miša Brkić, a renowned economic journalist, sharply analyses Serbia’s current economic and business landscape. From entrenched corruption and inflationary pressure to the challenges of EU integration and workforce emigration, he dissects the key factors shaping the country’s stagnation. In this interview, Brkić explains why Serbia struggles to move forward, how political decisions impact the economy, and what it would take to break free from the cycle of inefficiency and missed opportunities.

Student protests have been ongoing for over three months and have been characterised as anti-corruption demonstrations. How deeply has corruption taken hold of Serbian society?

Corruption is an endemic disease in Serbian society. In other words, it is nothing new. However, it has exploded over the past 12 years, becoming a mandatory systemic “stylistic device.” The moment the Serbian Progressive Party took complete control of the state and all local governments, a Pandora’s box of systemic corruption was opened. The government was left without external oversight from independent regulatory and control institutions, whose role it deliberately minimised and ultimately destroyed.

In previous years, corruption was primarily encountered in healthcare, the police, and local government offices. However, it has since metastasised throughout the entire system, becoming its key component. The recent wave of arrests we have witnessed in recent days illustrates just how deeply corruption has spread, branching out and ultimately devastating both the state and society.

How to Fight Corruption?

How to Fight Corruption?

When we look at the level of corruption created by the Serbian Progressive Party today, it may seem that any fight against it is futile. But it is not.

Although Serbia ranks high among the world’s most corrupt countries and the battle appears impossible, there are still methods, measures, and mechanisms to curb it.

The first and most important step is to reduce the size of the state and limit its power by cutting down the regulations it imposes on markets. A minimalist state, focusing on just four or five key areas (such as border security, foreign policy, judiciary, and citizen protection), is the first guarantee of reducing corruption. Next, the number of laws and regulations granting excessive authority to the state must be drastically reduced, as such a system naturally breeds corruption.

Beyond this, classic operational methods for combating corruption must be applied. Chief among them are strict laws, intensified and expanded criminal prosecution, and the enforcement of severe sanctions. However, this alone is not enough. Additionally, more sophisticated instruments are required.

One such tool is a systematic examination of hundreds of administrative procedures to eliminate any opportunities for corruption in state operations. Another is public education and mobilising public opinion to support law enforcement. In other words, enforcement, prevention, and education must be implemented simultaneously and in coordination.

A government genuinely committed to fighting corruption must establish an independent commission responsible for overseeing and implementing these three elements. This commission should include an investigative unit composed of professionals—accountants, economists, and legal experts—trained to identify regulation loopholes and detect potential corruption risks.

Every month of delay in European integration feels like a year of lost progress

What Will Happen to NIS After US Sanctions? Could There Be an Energy Crisis?

We have already seen signs of disruption, such as Wizz Air—a company backed by American capital—briefly halting fuel refuelling at Belgrade Airport because NIS is its sole supplier.

As of today (24 February), there are still no clear indications of how the Serbian-Russian-American oil dispute will unfold. The key issue revolves around the Russian company Gazprom’s stake in NIS. If the US insists on sanctions and Russia refuses to relinquish its ownership share, the only possible outcome would be NIS’s bankruptcy due to an inability to continue operations.

The consequences of bankruptcy are well known—for owners, creditors, business partners, competitors, and consumers alike. However, what truly matters is that the market continues to function and that consumers—whether car, truck, bus, or aircraft owners—have a steady fuel supply. If one supplier, in this case, NIS, is removed from the equation, other players will step in to fill the gap.

Have We Really Tamed Inflation? Serbia’s Prices Are Unreal

Have We Really Tamed Inflation? Serbia’s Prices Are Unreal

Serbia’s inflation may seem to be under control, but prices remain astonishingly high. Serbia is more expensive than many wealthier and more developed European countries. Why is that?

Let’s clarify one thing right away: The Serbian government ignited inflation during the COVID-19 pandemic. For three years, it poured so-called helicopter money into the economy, supposedly to help citizens and businesses weather the crisis. By its own admission, the government spent €9 billion this way. But economics is not a religion—this money, which was not backed by goods or services, eventually led to soaring inflation.

Many players influence prices: producers, distributors, retailers, and the state itself. Take fuel, for example: petrol prices in Serbia are among the highest in Europe because the government imposes hefty excise duties, which it channels into the budget to cover its own expenses. Serbia’s state apparatus is large, sluggish, expensive, and inefficient, driving production costs.

Another factor is the inefficiency of local producers, whose productivity and competitiveness are far below European standards. Retailers also play a role, taking advantage of weak competition to maximise profits. While foreign retail chains are currently under attack, it is worth remembering that they did not come to Serbia to act as charities but to generate profit. The government is responsible for setting fair rules and ensuring market competition.

Why doesn’t it do so? Simply put—because it is incapable.

Corruption has metastasised throughout the entire system, becoming its key component

How do you explain Germany’s industrial crisis? Could it affect Serbia’s economy, considering Germany is our largest foreign trade partner?

Many quickly blamed the disruption of Russian energy supplies as the primary cause of Germany’s industrial downturn. However, I see two far more significant reasons.

The first and most crucial is the lack of innovation. Germany’s industry has rested on its laurels for years—much like the entire European industrial sector. Innovation has been stagnant, and many of the most promising startups originating in Germany and Europe have relocated to the US for better business conditions. Germany’s rigid business environment and costly welfare state have become a heavy burden for industrialists.

The second reason is the flawed strategy of Germany’s political leadership (and the EU) in hastily setting deadlines for phasing out fossil fuels and forcibly introducing electric mobility in the automotive industry. Industrialists lacked the capital to meet this political directive, and even when they produced electric vehicles, consumer enthusiasm remained lukewarm.

The impact of Germany’s industrial crisis on Serbia’s economy is only just beginning to be felt. I have the impression that our politicians are either unaware of the looming consequences or are deliberately burying their heads in the sand, refusing to acknowledge the economic tsunami approaching from our most important trade partner.

Is this agreement a form of neo-colonialism? Are we on the path to becoming a German colony—if we aren’t one already?

I don’t subscribe to that kind of neo-colonial hysteria. Serbia cannot function as an isolated country on this planet. We are part of what former communists used to call the “international division of labour.” Our problem is that we participate in this system not with our intellect, knowledge, or skills, but with our natural resources.

In that sense, we are similar to Russia. They rely on oil and gas, while we have rare metals that we should utilise and integrate into the global economy. This isn’t colonialism—it’s globalisation, a process that, for example, China has benefited immensely from over the past 30 to 40 years.

Serbia is not a colony but on the periphery of global industrial and technological revolutions. Perhaps that is because we are too fixated on the past.

How Far Behind Is Serbia on Its European Path, and What Does That Mean for Our Economy?

Serbia is significantly lagging behind. It feels as though every month of delay is equivalent to a year of lost progress. We are witnessing a strange phenomenon in which the government’s rhetoric is full of commitments to European integration, while its actions are rooted in anti-European values and behaviour. This contradiction is understandable because true European values directly challenge the current regime.

The prolonged stalling of European integration is causing enormous harm to both the economy and the citizens. Any objective analysis will show the immense benefits that businesses, entrepreneurs, and citizens of Bulgaria, Romania, Poland, Croatia, and Slovenia have gained from joining the EU—and how this accession has driven economic growth and prosperity.

How Can Serbia Develop Its Economy Amidst Workforce Emigration?

How Can Serbia Develop Its Economy Amidst Workforce Emigration?

A growing number of skilled professionals—doctors, craftsmen, scientists, and drivers—are leaving Serbia. How can we stop this trend, and given our current economic situation, is it possible to fill the gaps with workers from third-world countries?

The answer lies in integrating Serbia’s labour market into the global division of labour. Poland and Romania did not collapse when they joined the European Union and saw their workforce move en masse to the UK and Italy. This is precisely why Serbia’s EU accession is crucial. A fully open labour market would give Serbia the opportunity to organise itself as a well-structured society that could attract workers from other EU member states.

Many economically developed countries have demonstrated that compensating for workforce shortages by importing labour from third-world countries can ensure economic growth and market stability.