A good man from Lisinski Street

“Dear friend, I’m not feeling very well currently. September is too far away for me to make any arrangements. Let’s stay in touch. Happy work! Mihal,” replied Mihal Ramač to my invitation to the Book Talk conference, which is happening at the end of September this year. We saw him the last time in October of last year when he spoke with other authors about his greatest gastronomic pleasures and read the recipe for the best borscht at Salaš 137 restaurant at our Food Talk conference.

When my colleague, Goca Nonin, informed me on May 13 that Miša had died, I think, after a series of bad news and tragic events in our country, that news hit me completely.

Miša was one of those wonderful, quiet people whose attitude and words would move mountains and run deep. When we separated from Independent Index in 1992 and founded Novosadski Index, he helped us, no-name kids, and students. We will never forget when he brought Mr. Hoffman, the then press attaché of the US Embassy in Belgrade, to our two-bedroom editorial office in Aleksa Šantić 3-5 Street, located at Grbavica, Novi Sad, which we rented from Dr. Pejin. That was in 1993, at the time of hyperinflation and total collapse. We served the man a Serbian snack called Smoki that we pulled from the drawer at the bottom of the refrigerator, and Suzana Šaćić, then a refugee from Bosnia and editorial secretary, and today, 30 years later, the director of our company in Sarajevo, went to the store to buy a Serbian chocolate spread called Eurokrem in a glass cup so that we would have a decent cup to offer him juice in. Afterward, we took him to the restaurant called Piroš Čizmafor for lunch – he ate gypsy roast. That year he sent his colleague Goca Jovanović with Duško Jovanić, and the following year, he sent me to the IVP in the USA.

I had met Miša two years earlier when, in September 1991, together with other members of the Independent Association of Journalists of Vojvodina, we spoke from Window in Zmaj Jovina Street in Novi Sad. That was a unique form of protest we organized during the war in Croatia, when every evening from the window of the IAJV premises at Zmaj Jovina 4, precisely at 7:30 p.m., we read the news that people could not hear on Milošević’s RTS, the Radio Television of Serbia.

What Miša was like and what his roots were is best described by the scene from his childhood that he shared himself: “I was not quite four years old when my parents took me to a play in my native village, Ruski Krstur, for the first time. As soon as there was some commotion on stage, I started screaming. They had to get out. No one raised their voice in our house. That’s why I was scared. There was no swearing. And even today, there is no cursing. My parents, poor peasants with elementary school education, went to a theatre performance in 1954.”

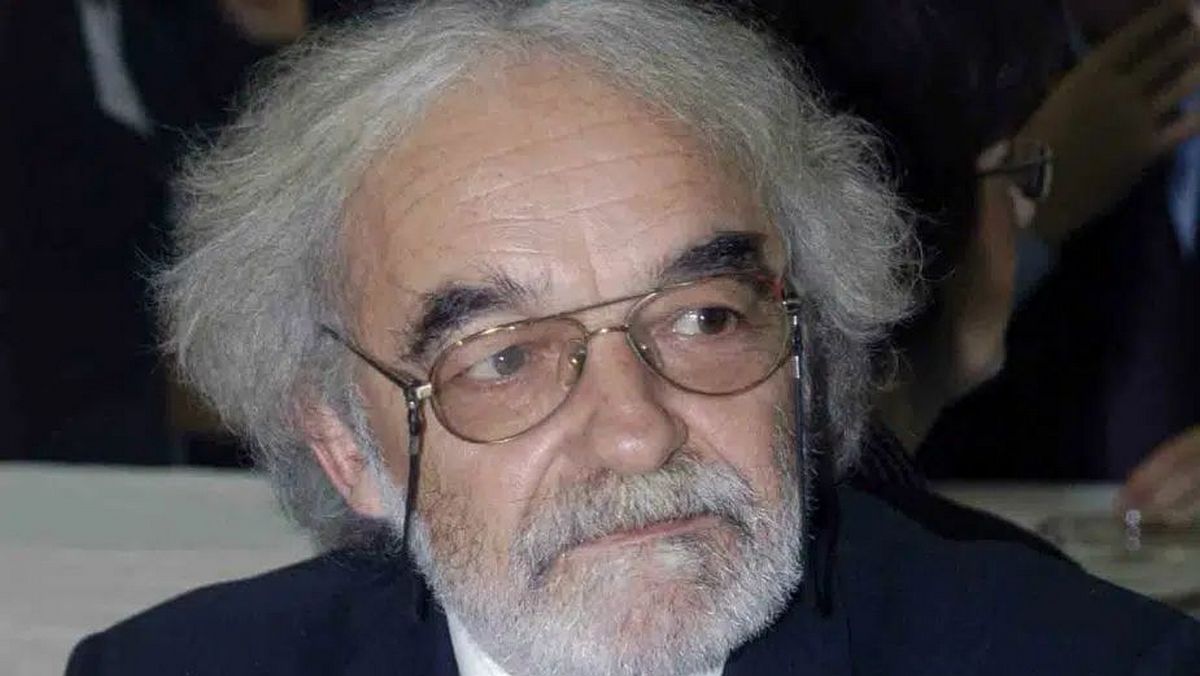

Mihal Ramač was born in 1951 in Ruski Krstur. He finished the classical Lyceum in Rome and graduated in history at the Faculty of Philosophy in Novi Sad. He was a journalist for the newspapers Ruske slovo and Dnevnik, a correspondent for Free Europe Radio and the Ukrinform agency, and before Danas, the editor-in-chief of the daily newspapers Naša Borba and Vojvodina.

He lived in Petrovaradin at Lisinski Street in Podgrađe. He published seven books of poems in the Ruthenian language. He published the scripts for seven TV series about the nineties of the 20th century.

He translated the Bible (2019) from Hellenic to Ruthenian with his brother Janko. He also translated into Ruthenian and from Ruthenian to Serbian about thirty books of poetry and prose in the periodicals of several dozen Yugoslav and world poets’ books of essays, including: The Story of the End (2002), On the Other Side of Dreams (2003), 6th October (2008), The Calling of Bright Vistas (2018), and Danube Rhapsody (2018).

My colleague, Gordana Nonin, wrote in Danas after Miša’s death: “The news echoed so painfully in the public that after a short and serious illness, Mihal Ramač had moved on to the other shore. An intellectual, journalist, editor, poet, writer, translator, publicist, and eternal fighter, he was a wonderful man who could always share a smile but also instantly retain the kind of seriousness on his face that only those who listen carefully to others possess. He was also among those who dared to immediately and publicly say no to wars and killing at the beginning of the nineties. And for decades to come, he unequivocally emphasized this with his every public appearance, text, and gesture. For example, at the promotion of his exceptional poetry collection Another shore – the patriotic and refugee poems (publisher: Most Art Jugoslavija, Zemun, 2020) – which was promoted last year at the Novi Sad Literary Festival on the caffe-ship Zeppelin on the Danube, he rose majestically and said that he dedicated the evening primarily to refugees from Ukraine and recounted the inhumane conditions they were in at the time!”

In the text Mihal and I, Aleksei Kišjuhas noted: “He was a democrat and cosmopolitan in politics, editorial office, and everyday life – critical of communism, and every type of nationalism. And above all, he was almost unbelievably kind, warm, tolerant, cheerful, and always wearing a smile. As if he was born in another or a different era? He was an honest and good man. That is the first thing that, after his death, everyone who knew him would write and comment about. How many of us will be able to boast of such epithets when we are gone? “When he comes to us, the whole day remains beautiful,” was the comment of one of the saleswomen in his neighbourhood. “He is a good father, grandfather, and husband. The only thing he couldn’t stand was human stupidity. For everything else, he was tolerant,” his wife wrote to me the night before he left us!”

I owe a lot more to Mihal Ramač. I hope that the journalistic and literary community of Vojvodina will arrange to keep his name alive through an award or a foundation.