OBITUARY

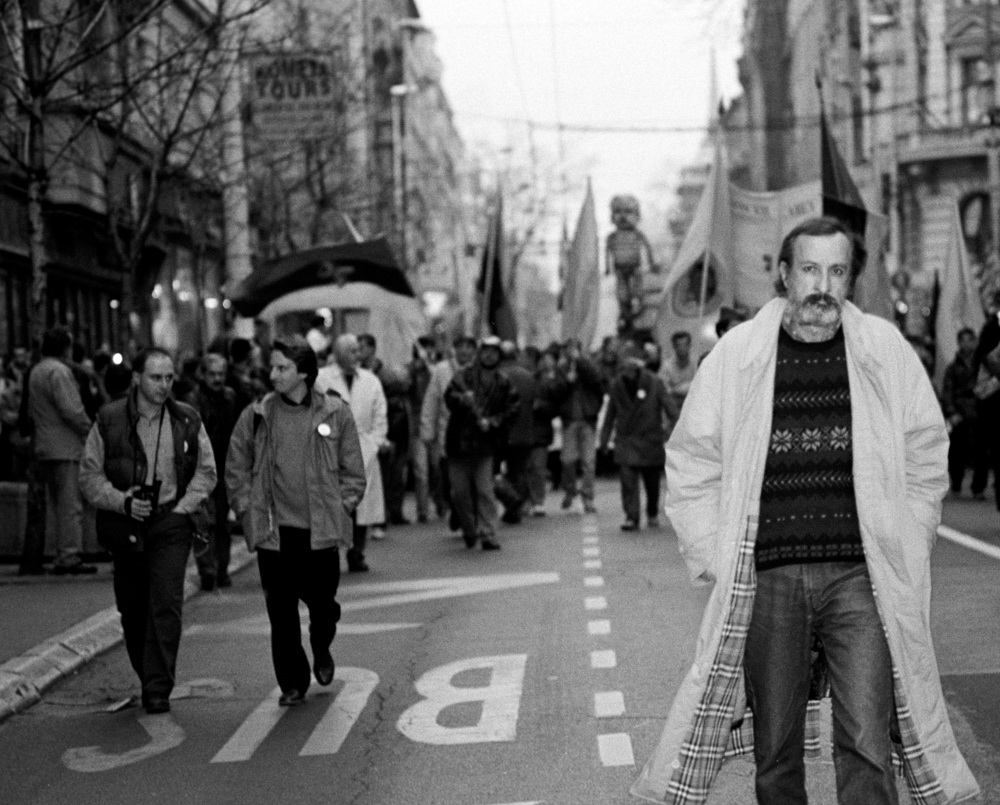

Dragoljub Raša Todosijević

1945 – 2024

The renowned artist Dragoljub Raša Todosijević, a pioneer of conceptual art in Europe and one of the most celebrated figures in Belgrade, Serbia, and Yugoslavia, passed away on 3 December at the age of 79, embarking on the “eternal hunting grounds”—as he might have put it. He would probably have been surprised by the hundreds of reactions on social media and the news of his death in global media outlets. However, he surely would not have been astonished by the lack of even brief condolences from officials in his hometown and the country he represented in prestigious global institutions, including the 54th Venice Biennale in 2009, where he won the Unicredit Venice Award for the best exhibition among Eastern European pavilions with The Light and Darkness of the Symbol.

Knowing him, he would have been least surprised by the absence of any mention of a potential burial in the Alley of Distinguished Citizens. “Thank you, Raša Todosijević. A grateful Serbia. Perhaps…” said Una Popović, art historian and senior curator at the Museum of Contemporary Art in Belgrade, during his cremation. The museum hosted Todosijević’s first major retrospective, ‘Thank You, Raša Todosijević’, in 2002.

Despite hundreds of professional analyses of his artistic practice—which encompassed drawings, paintings, graphics, collages, sculptures, objects, installations, performances, video works, posters, programmatic texts, and stories—Todosijević, as Una Popović noted, had the best ability to explain his work himself:

“If I had to describe myself—which is truly an ungrateful task—I would say that I am, above all, a European artist whose work consists of hard, mining-like digging into the consciousness and subconsciousness, but also the conscience of our ruthless civilisation.”

Starting in the early 1970s at the Student Cultural Centre (SKC) in Belgrade, alongside other members of the informal Group of Six Artists (Zoran Popović, Marina Abramović, Neša Paripović, Era Milivojević, and Gergelj Urkom), Todosijević built a career that earned him international acclaim. He won the most prestigious domestic awards (Ivan Tabaković Foundation Award of the Serbian Academy of Sciences and Arts, 2023; ULUS Lifetime Achievement Award, 2024; 50th October Salon Award, 2009; Nadežda Petrović Memorial Award, 1998; Sava Šumanović Award, 2008) and several renowned international honours (Stockholm Museum of Modern Art Award, IASPIS Residential Award, 2001; ArtsLink Award, 2004; and Emily Harvey Foundation Award in New York, 2006).

According to Todosijević, the SKC was one of the centres in former Yugoslavia where “young people, far beyond cultural, police, or political control, were doing some form of art.”

Although the freedom and working conditions institutionally afforded to his generation might seem like a dream to young artists today, the first few decades of his career, as he stated in an interview with SEEcult.org, were not “beautiful or pleasant times.” He considered his only illusion as a young artist to be the belief that enduring unpleasant and hostile circumstances would be short-lived and people would eventually recognise the value of his art. Unfortunately, that never happened, even after 40 or 50 years, and the same stigma towards “new artistic practice” persisted for over five decades.

Todosijević waited thirty years for a studio because “they thought he was involved in nonsense.” Later, in 2015, just before his 70th birthday, he lost his workspace because he refused to accept a 20-square-metre former grocery store in New Belgrade offered by the Poslovni prostor instead of his atelier in the Old Fairground area.

Todosijević advised young artists to flee Serbia. “An artist shouldn’t sit here and complain, deal with incompetent professors who know nothing, and seek happiness in a place without any money, wandering around, exhibiting in the provinces, and spending life in boundless greyness and animosity towards culture—not to mention modern art. We no longer even have art magazines. Why does the government not need culture or a cultural layer after all? Because it’s a numerically small population. What kind of voting machine are they? None. They need to nurture fools because they are the majority, and that’s that.”

His artistic practice, characterised by constant questioning, analytical depth, and direct politicisation as both a method and purpose of creative expression, is best summed up by one of his often-quoted statements: “The way an artist raises a question about art is, in itself, a work of art.”

by Vesna Milosavljević – SEEcult.org