Honouring History Through the Rebirth of Notre Dame

The day after the reopening of Notre Dame, the French press—and media worldwide—focused more on who Donald Trump warmly greeted (or didn’t) and which leaders attended in person versus who sent a representative rather than analysing the craftsmanship in stone wood, and glass within the cathedral itself. Even fairly convincing AI-generated “footage” of a brawl between Donald Trump and Jill Biden in the front row of Notre Dame made its way onto social media. But perhaps this reflects the spirit of the times we live in, a world significantly different even from that of 2019 when the cathedral burned.

The day after the reopening of Notre Dame, the French press—and media worldwide—focused more on who Donald Trump warmly greeted (or didn’t) and which leaders attended in person versus who sent a representative rather than analysing the craftsmanship in stone wood, and glass within the cathedral itself. Even fairly convincing AI-generated “footage” of a brawl between Donald Trump and Jill Biden in the front row of Notre Dame made its way onto social media. But perhaps this reflects the spirit of the times we live in, a world significantly different even from that of 2019 when the cathedral burned.

I was in Libya when the French Ministry of Foreign Affairs invited me to participate in a seven-day programme on the protection of cultural heritage. The highlight of the carefully crafted programme for me and three other colleagues (from Argentina, Germany, and the USA) was the official reopening ceremony of Notre Dame Cathedral. I was tired from my travels, but such an invitation was impossible to refuse.

During that week, the French aimed to demonstrate how we might transfer their approach to our societies—the meticulous and precise manner in which they employ culture as a cornerstone of their “soft power.” By culture, I mean the broadest interpretation of the term: from the spectacular opening of the Summer Olympics in July this year to the celebration of wine at the Cité du Vin in Bordeaux, the world’s largest interactive wine museum. This invitation came as a result of my longstanding work on the project “Castles of Serbia: Protecting Cultural Heritage,” as well as my public engagements and writings on the topic.

During that week, the French aimed to demonstrate how we might transfer their approach to our societies—the meticulous and precise manner in which they employ culture as a cornerstone of their “soft power.” By culture, I mean the broadest interpretation of the term: from the spectacular opening of the Summer Olympics in July this year to the celebration of wine at the Cité du Vin in Bordeaux, the world’s largest interactive wine museum. This invitation came as a result of my longstanding work on the project “Castles of Serbia: Protecting Cultural Heritage,” as well as my public engagements and writings on the topic.

It took over 200 years to build, only a few hours to burn, and five years to restore

Emmanuel Etienne, Assistant Director for Heritage and Architecture at the Ministry of Culture, explained how the state oversees architectural heritage not only in mainland France but also in its overseas departments—from French Guiana, Guadeloupe, and Martinique in Latin America to Réunion Island in the Indian Ocean, and French Polynesia (Tahiti) and New Caledonia in the Pacific. When considering the geographic distribution and size of some of its overseas territories, France could still carry the nickname once associated with the British Empire.

What sets France apart in the preservation of architectural heritage—and is key to understanding Notre Dame itself—is the fact that Catholic churches within its territory, as a result of revolutionary achievements, are state-owned! Local authorities manage smaller ones, while the larger and more significant ones are under the care of the Fifth Republic.

What sets France apart in the preservation of architectural heritage—and is key to understanding Notre Dame itself—is the fact that Catholic churches within its territory, as a result of revolutionary achievements, are state-owned! Local authorities manage smaller ones, while the larger and more significant ones are under the care of the Fifth Republic.

Valérie Brisset, Deputy Director for Cultural, Educational, and Academic Diplomacy at the French Ministry of Foreign Affairs, spoke to us about the network of French Institutes worldwide—present in 110 countries and employing as many as 5,000 people. In China, where she previously worked, the French Institute employs over 400 individuals dedicated to promoting their country’s “soft power.” A key focus of their efforts is the process of restitution—the return of artworks taken to French museums during the colonial period. This programme, launched by President Macron in 2017, is being gradually and carefully implemented through numerous bilateral agreements, with artworks primarily being returned to African and Asian countries once part of the French colonial empire. In the opposite direction, France provides safe storage for artworks from war-affected countries, recently receiving many valuable Ukrainian icons. France also funds many archaeological missions worldwide, currently totalling 160.

Long live Notre Dame of Paris, long live the Republic, and long live France!

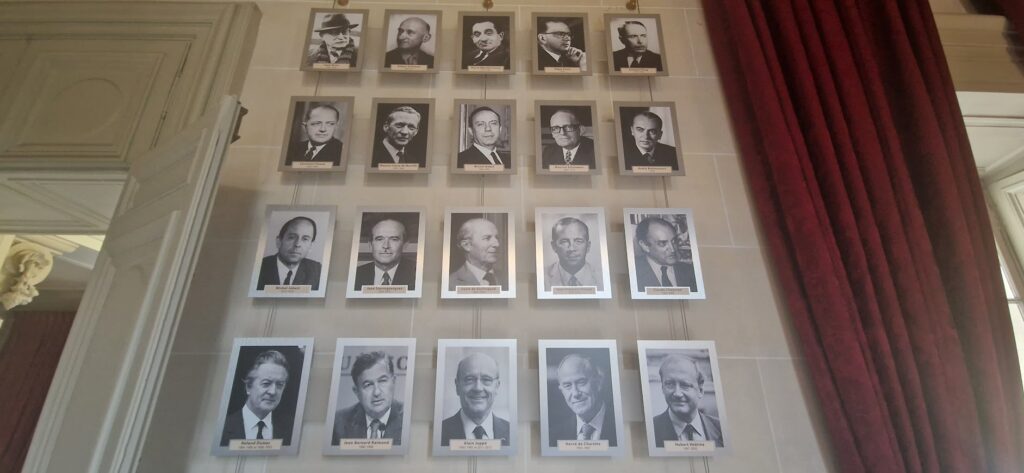

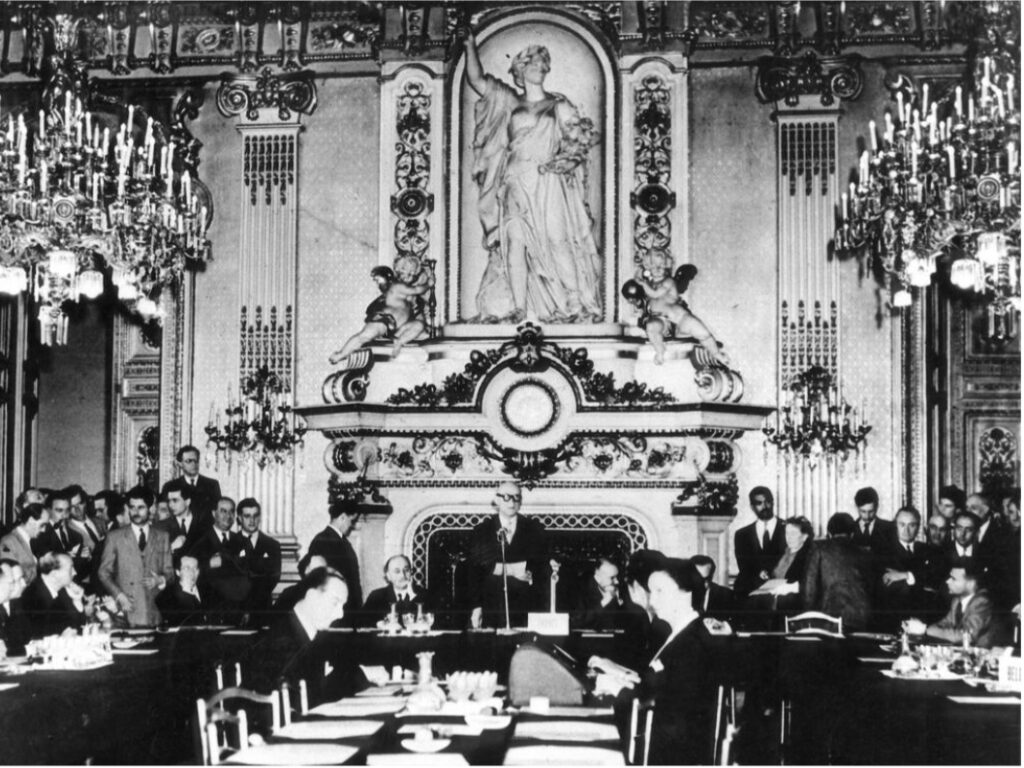

The Salon de l’Horloge, a room within the French Ministry of Foreign Affairs, holds historical significance as the place where, on June 20, 1950, French Minister Robert Schuman announced the implementation of the Schuman Plan, marking the beginning of the European Union as we know it today. He proposed placing the coal and steel production of France and West Germany under a single authority, which would later be open to other European states. The ultimate aim was to ease tensions between France and West Germany through gradual political integration based on shared interests. “To create a community of nations, it is essential to eliminate the centuries-old enmity between France and Germany,” he said. At the entrance, the walls feature photographs of all former Foreign Ministers, including Louis Barthou, who was assassinated alongside King Alexander in Marseille in 1934.

In one of the adjacent rooms, we were served lunch hosted by Christophe Lemoine, the spokesperson and director for media and communications at the Ministry of Foreign Affairs. The delicious early lunch at 12:30, accompanied by generous servings of red wine (Chateau le Crock, 2016), evolved into an open exchange of views on France’s “soft power” strategy, particularly against the backdrop of the country’s political crisis (the Prime Minister lost his majority in Parliament during our visit). Perhaps the most significant insight we gained from nearly all our interlocutors was their acknowledgement that the budget and concept of France’s “soft power” remain consistent regardless of changes in leadership or government—a stark contrast to our practices.

In one of the adjacent rooms, we were served lunch hosted by Christophe Lemoine, the spokesperson and director for media and communications at the Ministry of Foreign Affairs. The delicious early lunch at 12:30, accompanied by generous servings of red wine (Chateau le Crock, 2016), evolved into an open exchange of views on France’s “soft power” strategy, particularly against the backdrop of the country’s political crisis (the Prime Minister lost his majority in Parliament during our visit). Perhaps the most significant insight we gained from nearly all our interlocutors was their acknowledgement that the budget and concept of France’s “soft power” remain consistent regardless of changes in leadership or government—a stark contrast to our practices.

The restoration of this awe-inspiring church will serve as a prophetic sign of the renewal of the Church in France

That afternoon, we visited Versailles, the palace of French kings, where Marie Antoinette was taken before being guillotined, where the Treaty of Versailles was signed in 1919, and where director Peter Brook wasn’t allowed to film Alexander of Yugoslavia. Walking through the bedrooms and halls of Versailles, alongside invaluable works of art, I reflected on how, throughout the past two and a half centuries of kingdoms, two empires, five republics, and even two German occupations, the French have never allowed “greater interests” to overshadow their dedication to cultural heritage—churches, palaces, paintings, sculptures, and even furniture and garments.

On that note, we also visited Le Mobilier National, an institution dedicated to restoring and maintaining historically significant furniture owned by the state. It was astonishing to witness the meticulous care with which experts worldwide work on restoring these valuable pieces, often dedicating more than a year of daily effort to a single item.

On that note, we also visited Le Mobilier National, an institution dedicated to restoring and maintaining historically significant furniture owned by the state. It was astonishing to witness the meticulous care with which experts worldwide work on restoring these valuable pieces, often dedicating more than a year of daily effort to a single item.

A similar mission, though broader in scope, is carried out by the Institut National du Patrimoine (National Institute of Heritage). At their facility, housed in a former matchstick factory, we were greeted by the director, Charles Personnaz, who patiently guided us through various departments—painting, wood, photography, graphic art, and metal—where we engaged with young experts working on conserving individual artefacts. Among them, we met a young woman born in France but of Serbian origin, who is likely to become the kind of specialist our country desperately needs. If only someone from Serbia could extend an invitation to her.

On our final day, we had the privilege of visiting another significant institution of French culture, the Institut de France. This esteemed body encompasses five academies: the French Academy (L’Académie française), the Academy of Sciences (Académie des sciences), the Academy of Humanities (Académie des inscriptions et belles-lettres), the Academy of Fine Arts (Académie des Beaux-Arts), and the Academy of Moral and Political Sciences (Académie des Sciences Morales et Politiques). Established in 1795, the Institute was founded to unite the scientific, literary, and artistic elite, promote advancements in science and art, foster independent thinking, and advise public authorities, all on a non-profit basis. The Institute operates under the patronage of the President of the French Republic, and its current Secretary, elected for a three-year term, is Xavier Darcos.

On our final day, we had the privilege of visiting another significant institution of French culture, the Institut de France. This esteemed body encompasses five academies: the French Academy (L’Académie française), the Academy of Sciences (Académie des sciences), the Academy of Humanities (Académie des inscriptions et belles-lettres), the Academy of Fine Arts (Académie des Beaux-Arts), and the Academy of Moral and Political Sciences (Académie des Sciences Morales et Politiques). Established in 1795, the Institute was founded to unite the scientific, literary, and artistic elite, promote advancements in science and art, foster independent thinking, and advise public authorities, all on a non-profit basis. The Institute operates under the patronage of the President of the French Republic, and its current Secretary, elected for a three-year term, is Xavier Darcos.

We toured the hall where academics meet—each academy holds its sessions on different days of the week—and the library. I proudly mentioned that Vladimir Veličković, the renowned Serbian painter and French academician, once sat here; he was the father of artist Vuk Vidor. Interestingly, the French academies only began admitting women after the 1970s, and today, women make up less than 10% of their membership. This year, the French Academy published the 9th edition of the Dictionary of the French Language, launched on November 14 by President Macron. The previous edition, the 8th, was published in 1935, while the very first—Le Dictionnaire de l’Académie françoise—was a pre-edition printed in Frankfurt in 1687.

We toured the hall where academics meet—each academy holds its sessions on different days of the week—and the library. I proudly mentioned that Vladimir Veličković, the renowned Serbian painter and French academician, once sat here; he was the father of artist Vuk Vidor. Interestingly, the French academies only began admitting women after the 1970s, and today, women make up less than 10% of their membership. This year, the French Academy published the 9th edition of the Dictionary of the French Language, launched on November 14 by President Macron. The previous edition, the 8th, was published in 1935, while the very first—Le Dictionnaire de l’Académie françoise—was a pre-edition printed in Frankfurt in 1687.

Over €840 million was raised for the restoration—the most significant amount ever collected to preserve a cultural monument

Saturday, December 7, finally arrived—the day of the grand reopening of Notre Dame Cathedral. Weather forecasts predicted rain, so the organisers decided to avoid a repeat of the misfortune that plagued the Summer Olympics opening ceremony in July, moving the event indoors under the cathedral’s vaults at the last moment.

It took over 200 years to build, only a few hours to burn, and five years to restore. The iconic Notre Dame Cathedral in Paris has once again opened its doors—marking its first public event since the devastating 2019 fire that nearly destroyed this symbol of Paris, France, and one of the most famous churches in the world. The word merci (“thank you”) was projected onto the cathedral’s façade, expressing gratitude to everyone who contributed to restoring this 860-year-old landmark, heavily damaged in the catastrophic blaze five years ago.

It took over 200 years to build, only a few hours to burn, and five years to restore. The iconic Notre Dame Cathedral in Paris has once again opened its doors—marking its first public event since the devastating 2019 fire that nearly destroyed this symbol of Paris, France, and one of the most famous churches in the world. The word merci (“thank you”) was projected onto the cathedral’s façade, expressing gratitude to everyone who contributed to restoring this 860-year-old landmark, heavily damaged in the catastrophic blaze five years ago.

Unlike the excellent seven-day cultural heritage tour organised by the French Ministry of Foreign Affairs for the four journalists from around the world (Argentina, Germany, the USA, and Serbia), the Élysée Palace, responsible for the Notre Dame reopening ceremony, fell far short of expectations.

We had been having lunch in the Latin Quarter, just a five-minute walk from the cathedral. At the designated time, I headed to the security checkpoints, confident that the wristband I had received the day before and my press accreditation, complete with an assigned seating area, would be sufficient for smooth entry. However, crossing the Seine from the southern part of the city to the event location proved impossible. We were sent from one bridge to another, with police officers who didn’t speak English and no organisers around to assist. Everyone shook their heads, and neither my valid accreditation nor wristband seemed to matter.

We had been having lunch in the Latin Quarter, just a five-minute walk from the cathedral. At the designated time, I headed to the security checkpoints, confident that the wristband I had received the day before and my press accreditation, complete with an assigned seating area, would be sufficient for smooth entry. However, crossing the Seine from the southern part of the city to the event location proved impossible. We were sent from one bridge to another, with police officers who didn’t speak English and no organisers around to assist. Everyone shook their heads, and neither my valid accreditation nor wristband seemed to matter.

After an hour of walking from Pont Saint-Michel to Pont Neuf and then to Petit Pont Cardinal Lustiger (at least I learned the names of the bridges), a sympathetic policewoman finally allowed me to cross to the island housing the iconic cathedral.

I made my way to the journalists’ section, which was overseen by “monitors” who were quick to remind us not to stand (even when everyone else in the church was standing) or not to film (while everyone else was recording). Naturally, before the official ceremony began at 7:00 p.m., I left this “restricted area” and ventured to the seating reserved for Macron, Trump, Prince William, and other dignitaries.

The firefighters who helped save the masterpiece of Gothic architecture, along with those who worked on its restoration, received a standing ovation from attendees after the Archbishop of Paris, Laurent Ulrich, ceremonially struck the doors of Notre Dame three times with his staff to officially reopen the cathedral. “On behalf of the French nation, I express our gratitude to all who saved and rebuilt this cathedral,” said French President Emmanuel Macron in his brief speech. “Tonight, we can share joy and pride. Long live Notre Dame of Paris, long live the Republic, and long live France!”

The firefighters who helped save the masterpiece of Gothic architecture, along with those who worked on its restoration, received a standing ovation from attendees after the Archbishop of Paris, Laurent Ulrich, ceremonially struck the doors of Notre Dame three times with his staff to officially reopen the cathedral. “On behalf of the French nation, I express our gratitude to all who saved and rebuilt this cathedral,” said French President Emmanuel Macron in his brief speech. “Tonight, we can share joy and pride. Long live Notre Dame of Paris, long live the Republic, and long live France!”

Macron greeted guests in front of the cathedral, including newly elected U.S. President Donald Trump, who attended without his wife Melania. Similarly, Prince William came without Princess Kate. French journalists around me made sarcastic remarks about Trump’s expressions as he viewed the interior of the cathedral, and they were even more amused by Elon Musk, who was also in attendance and frequently appeared on the screens lining the cathedral walls.

Pope Francis called it a day of “joy, celebration, and praise.” In a message read aloud during the ceremony, the Pope expressed hope that “the restoration of this awe-inspiring church will serve as a prophetic sign of the renewal of the Church in France.” Notably, France is among the European countries with the highest percentage of atheists, with 51% of the population identifying as unaffiliated with any religion, 29% identifying as Catholic, and 10% as Muslim.

Apart from the firefighters, the loudest applause was reserved for Ukrainian President Volodymyr Zelensky. Bringing Trump and Zelensky together at the reopening and organising a meeting at the Élysée Palace before the ceremony was a major diplomatic success for Macron, who is currently facing a political crisis at home after Parliament voted to impeach his Prime Minister.

Apart from the firefighters, the loudest applause was reserved for Ukrainian President Volodymyr Zelensky. Bringing Trump and Zelensky together at the reopening and organising a meeting at the Élysée Palace before the ceremony was a major diplomatic success for Macron, who is currently facing a political crisis at home after Parliament voted to impeach his Prime Minister.

Among the guests were Italian Prime Minister Giorgia Meloni and former French presidents François Hollande and Nicolas Sarkozy. Representing Serbia, which donated €1 million for the restoration of Notre Dame immediately after the fire, was Prime Minister Miloš Vučević. Croatia was represented by Minister of Culture and Media Nina Obuljen Koržinek, although President Zoran Milanović had initially been expected to attend. In addition to Trump, the United States was represented by First Lady Jill Biden. In total, slightly over 1,500 people were present in the iconic Parisian cathedral that evening.

The first stone of Notre Dame was laid in 1163, and construction continued through much of the following century, with significant renovations and additions made in the 17th and 18th centuries. After the fire, donations poured in from around the world, with over €840 million raised for the restoration—the most significant amount ever collected to preserve a cultural monument. The cathedral’s organ, with 8,000 pipes, was meticulously restored and cleaned of toxic lead dust during the restoration. At the reopening ceremony, four organists filled the sacred space with music that inspired awe and reverence.

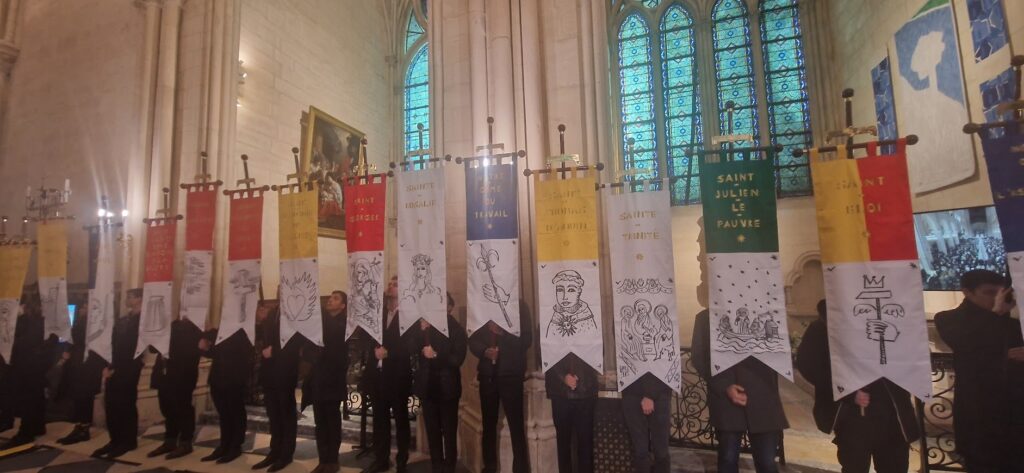

The following day, Archbishop Ulrich led the first mass in the restored cathedral and consecrated a new altar designed by contemporary artist Guillaume Bardet to replace the one destroyed in the fire. Nearly 170 bishops from France and abroad attended the mass, along with priests from all 113 parishes of the Archdiocese of Paris.

The following day, Archbishop Ulrich led the first mass in the restored cathedral and consecrated a new altar designed by contemporary artist Guillaume Bardet to replace the one destroyed in the fire. Nearly 170 bishops from France and abroad attended the mass, along with priests from all 113 parishes of the Archdiocese of Paris.

The day after the ceremony, the French and international media focused more on whom Trump greeted warmly (or not) and which heads of state attended versus who sent substitutes rather than on the craftsmanship of the cathedral’s stone, wood, and glass. Social media even saw the circulation of surprisingly convincing AI-generated videos depicting a supposed fight between Donald Trump and Jill Biden in the front row of Notre Dame. This reflects the spirit of our times, which is markedly different from the world of 2019 when the cathedral burned.

On Sunday, news broke that Assad’s regime in Syria, a former French colony, had fallen. Meanwhile, Notre Dame, bells, and bell ringers returned to where they had always belonged—in travel guides, films, and books—likely a more comfortable place for them than front-page headlines or viral social media stories.