I founded FoNet at the age of 35, and this year, I am turning 64

I love this job and nothing has changed about that. Survival is not the answer. The solution is to create prerequisites and opportunities for development and longevity.

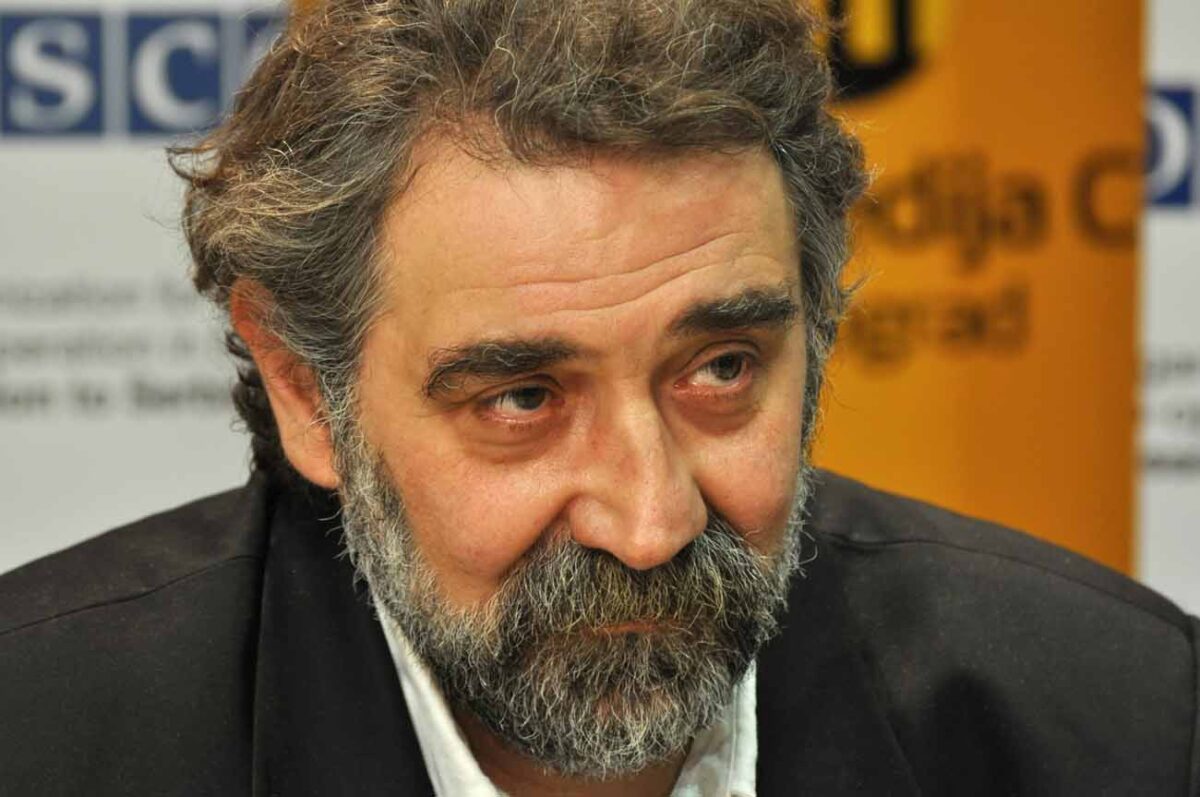

Zoran Sekulić, owner and editor-in-chief of FoNet, speaks about the news agency’s past 28 years, the hard times, the best times, the media coverage of the Ukrainian crisis, safety of journalists, but also about the future of news agencies.

As a former special reporter from the European Union, NATO and the Kremlin, could you comment on the current media coverage of the events in Ukraine? Do you condemn censorship of the Russian media?

I generally condemn the censorship of all media outlets that act as media outlets. Those who do not behave in this way are engaged in propaganda, but even then it is a very delicate matter to resort to restrictive measures. There are other ways in which society and the public can respond to classical propaganda. I have a problem with generators of hate speech, conspiracy theories and campaigns against people and communities, be they religious, ethnic or sexual. So, as far as the way of reporting is concerned, and if we are talking about serious and real media, they have the right to exercise their editorial policy. They have no right to fabricate half-truths and illusions, no matter who they support. As long as they practice the profession properly, adhere to the journalistic code of conduct and uphold the facts, I have no problem with that.

“The people in the media obviously serve as a big figurative ‘fig leaf’. Without the political will to implement them, even the best laws and strategies make no sense”

Reporting in Serbia about the war in Ukraine deviates to a greater or lesser extent from the official policy of this country. The editorial policy of the traditional mainstream media, which have the highest public visibility, varies from moderate to openly pro-Russian. I gather that people in Serbia are not fully or promptly informed about what is happening in Ukraine in a balanced and comprehensive manner.

In most of the most influential media, you can clearly see the political influence, be it direct, by order, or voluntary in the form of recommendations to the authorities. Such a situation affects the state of affairs in which the facts are no longer or are increasingly less important. Emotions and presumed beliefs of the audience are important. But this kind of reporting is to the detriment of the public and the media alike.

Ten years ago, you received the OSCE Person of the Year Award for your contribution to media reforms in Serbia. In 2016, you were the recipient of the French Order of the Legion of Honour, and in 2020, the German Order of Merit, both for your contribution to media freedom and freedom of speech. Were those reforms effective and what kind of media reforms do we need today?

I still had some illusions back then. Regardless of media strategies, laws and proclaimed reforms, I realized that it was all a big illusion. The government, this or other, has a very formal approach to the reforms as if they are just a bunch of obligations they need to fulfil towards someone. In essence, all this time, there has been no basic political will for the media scene to be regulated and for the media to work freely, responsibly and in the best public interest, and not in the interest of various formal or informal power centres. Media should not be attacked, journalists should not be targeted, their houses should not be set on fire, and the word of the law should be consistently respected and applied. In 2014, the passing of new media laws was applauded. The government, the EU, the OSCE and even the media community applauded. New regulations resulted in a Copernicus-like U-turn. The state was supposed to withdraw from ownership of the media, there was supposed to be no more direct budget financing for the media and everything looked almost idyllic. However, eight years have passed since then and we already have a new media strategy, so the existing or new media laws will be changed in line with the strategy. However, even the earlier media laws have not been implemented properly – they were not applied at all, improperly applied, or even abused. The people in the media obviously serve as a big figurative ‘fig leaf’. Without the political will to implement them, even the best laws and strategies make no sense.

Last year, you received threats after one of your TV appearances. What should we do to change such an atmosphere in society and reduce the pressure on the media and journalists?

Compared to what my colleagues experienced, my case is laughable. Everyone involved in journalism and exposed to attacks and pressure, must report that and make it public. The institutional order of the process should be respected, regardless of whether the institution will take action or whether it can and wants to. Such cases should be reported and at least somewhere registered that they happened.

Serbia is a deeply divided, polarized and even antagonistic country. A good part of the public discourse is based on the discrediting of others and different opinions and the suppression of dialogue and pluralism. When you keep repeating that a certain person is a foreign mercenary or a traitor of a country, you create such an environment where it is no longer a coincidence that someone threatens you, either on the street or from the podium. Basically, you become a sitting duck.

“Everyone involved in journalism and exposed to attacks and pressure, must report that and make it public”

The key here is having the responsibility for the words uttered in public, and this goes for the media, public stakeholders, the government and the opposition, regardless of differences in their positions. The authorities’ capacity to create such an environment is greater, but they are also more responsible. The government must want to create a social environment that will foster a civilized dialogue of dissidents, which, in my opinion, is the only way to reach a solution for the common good because if everyone thinks the same, nobody’s thinking at all.

After working for Radio 202, you worked for Tanjug for nearly a decade. What is your relationship with the competition, including the Beta news agency?

The Tanjug from the 1980s cannot be compared to the Tanjug from the 1950s and especially not to the Tanjug from the 1990s or the Tanjug from the transition to the present day. In the 1980s, Tanjug had over a thousand employees and 48 bureaus around the world. After the biggest global commercial news wires such as Reuters or the Associated Press, Tanjug was the sixth or seventh most influential news agency in the world. At Tanjug, I learned all about agency journalism and had ample opportunity to progress. As a relatively young journalist, I was in a situation to cover the most important events in the country and the world that had to do with Yugoslavia, and later with the Yugoslav crisis. The agency trust me implicitly, which I hope, was justified, so much so that at the beginning of the disintegration of Yugoslavia, I reported about all the key events related to Yugoslavia’s destiny. In 1991, I was also appointed the youngest editor of the political section in the history of Tanjug. I was barely 33 years old. Tanjug was a federal media outlet and on the eve of the country’s disintegration, the state authorities started to control “their” media.

For the longest time, Borba and Tanjug resisted being controlled first by the federal and then Milošević’s government. Unlike the Serbian Broadcasting Corporation (RTS), where people who opposed the official editorial policy, hate speech and war propaganda were immediately fired, Tanjug experienced an implosion because it differentiated itself in favour of Milošević. When the war in Bosnia started, I resigned as editor because I disagreed with editorial policy. When I embarked on an adventure with FoNet in early 1994, there was no competition or market per se. Tanjug had a dominant and privileged position on all grounds. Later, I expected that the new government would open the media scene, ensure equal footing for all of us and amortize Tanjug’s privileged status and financial position, but that did not happen. Here we are, 22 years after the fall of Milošević, and Tanjug is still privileged, while the attitude towards FoNet and Beta is still discriminatory. As for the relations between FoNet and Beta, they are collegial and friendly. We are in the same predicament.

During its 28 years, FoNet has survived wars, sanctions, the bombing of Serbia, government changes, economic crisis and pandemic. Which periods were the hardest and which the best?

Times have never been ideal, good or easy. They were bad, hard and worse. I could say that the 1990s were tantamount to a mental health diagnosis. I get scared when I remember how we made FoNet out of nothing and with nothing. That could only happen then and never again. If I had known what was in store for me when I founded a news agency, I would not have done it. Not even in my wildest dreams. Also, if I hadn’t done it, I would have never forgiven myself. That was a life-threatening time – years of occupational therapy, money shortages, uncertainty and indescribable sacrifices. For a media outlet like FoNet, which has been tirelessly defending its editorial integrity and sovereignty, political and financial circumstances are still far from normal and the resources far below of the mainstream media. We stagnated for years. In the 1990s, we were sued based on the draconian Information Law. Both times we were sued because we reported the news based on facts and both times we were sued together with Danas.

The 1990s were a nightmare. Then came the era of perpetual struggle for survival and efforts to maintain news production while, at the same time, developing at a snail’s pace. Now, it is not a matter of surviving, but rather developing, growing and taking one step forward, two steps back. I founded FoNet at the age of 35, and this year, I am turning 64. I love this job and nothing has changed about that. Survival is not the answer. The solution is to create prerequisites and opportunities for development and longevity.

What will the future of news agencies be like and what will FoNet face in the coming period?

News agencies need to adapt to the new reality. Our audience is no longer just traditional media. Also, when we talk about social networks, it is important which network we are talking about. In line with that, we need to adapt news production to new audiences on new platforms, which have themselves become creators of media content too. The race against time, i.e. to be the first in something, no longer exists. We can only play the card of credibility and trust. We also produce well-crafted content for new audiences in the virtual world and traditional media users alike. This is the content that is created following the journalistic code of conduct, in a way that is acceptable and necessary to them, adapted to the digital era. We are looking for new forms, changing storytelling and combining multimedia with text.

We also combine media platforms and we interact between different media content. The challenges here are enormous and should be viewed without prejudice, with an open mind. We have to forget a good part of the previous experience of how journalism used to work. Without giving up basic professional and ethical values, we must dress the media in a suit that is better tailored and more contemporary. Those who do not understand this will fail and will continue to function in ‘the Stone Age’.