How did it happen that Fruška Gora’s monasteries shine covered in gilded panels and freshly painted facades, while the villages in their shadow are decaying?

Fruška Gora’s monasteries, all restored and beautifully maintained, stand next to eponymous nearby villages, where every second house is abandoned and every third one is demolished or on the verge of being demolished. The culture halls there are empty and dilapidated, just like the buildings of the former social agricultural estates. It seems that the gap between the wealth of the Church and the townspeople who live in the shadow of its bell towers has not been greater since the Middle Ages.

Dusk had already settled when I entered the village of Bešenovo. According to the 2011 census, this village at the foot of Fruška Gora had a population of 841. Waiting for the final data of the new census, the locals say that today there are no more than 600 of them. The Church of St. Archangel Gabriel from 1814 is perked up in the centre of the village, whose front part with the tower has been freshly painted in yellow and white.

“A thousand people used to sit here and listen to the singing competition called ‘Glas Srema,” a man in front of the shop across the street from the church tells me and points to the former Culture Hall and Cooperative House, which have been abandoned since 2007 and today look like a set for a horror movie. Land lease contracts are scattered across the offices, walls are ‘adorned’ by graffiti accusing (Boris) Tadić of “betraying Kosovo”, the performance stage is now covered in rubble and garbage, the roof is cracked and you can clearly see the Moon through it.

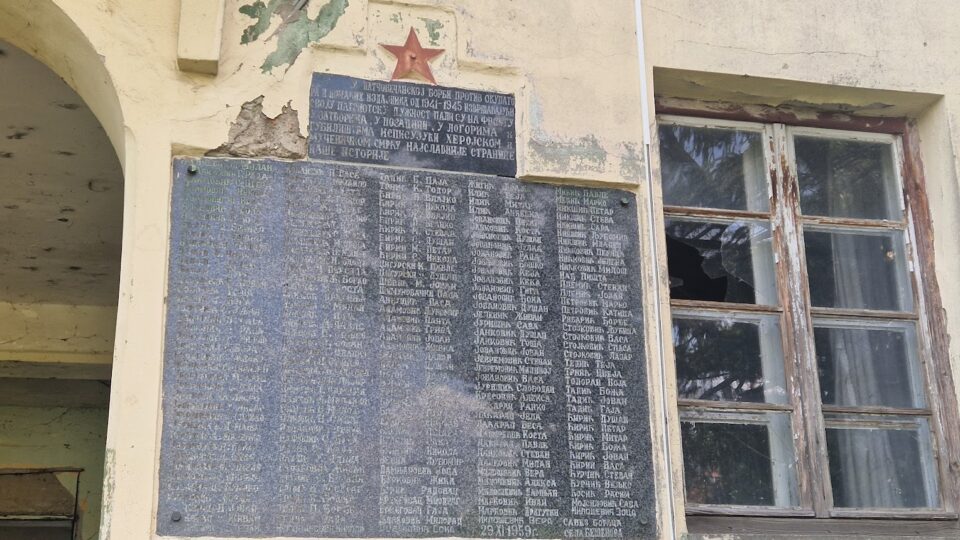

In front of the dilapidated and abandoned building, there is a sign with the names of the locals who died fighting in the Second World War and as victims of fascist terror – 187 inhabitants of Bešenovo, which is a huge number for such a small village. It is especially sad to see that this memorial is completely neglected and covered in weed, while some of the plaques are broken as the names of the freedom fighters etched on the plaques were not the fathers and grandfathers of the very people who live in this village.

The following weekend we returned to Bešenovo and continued on our journey. After visiting the Bešenovo Lake, which is located in the abandoned pit of the Beočin cement factory, we climb through the forest and reach the Bešenovo settlement that, like all the other settlements here, was erected right next to the monastery.

Grgetek village is known for a rather infamous record – it has fewer inhabitants today than there are names on the memorial plaque erected in honour of the WWII victims from the village

The windows of the abandoned cultural hall in the settlement are plastered with obituaries. In front is the bust of Sima Relić, the first commander of the Fruška Gora Partisan Unit. According to the 2011 census, the village had a population of 83. Today, there are many cottages here which are occasionally occupied, but truth be told, no more than 20 people are living here. Above the village is the Fruška Gora Art Camp whose gates are guarded by two wooden sculptures. Painter Branka Kolundžić and sculptor Miroslav Kovačević Koča, from Ruma, came to the Bešenovo settlement 15 years ago. Here, on a glade, at an altitude of 300 metres, they decided to build a family nest and form the Fruška Gora Art Camp. However, Koča died in the summer of 2020, so the estate seems quite deserted today.

During the Second World War, the monastery was destroyed by the Ustasha (Nazi collaborators, translator’s note) and then bombed in 1944, near the end of the war. Brother Dragan from the brotherhood of this male monastery kindly welcomes us and tells the details of the dramatic history of Bešenovo: “The Germans took off in a bomber that was stationed near Grgurevci and bombed the monastery from the air. Everything was destroyed!” Only parts of the iconostasis have been preserved. Since Bešenovo suffered to such an extent in WWII, it was not rebuilt in the decades after. Until 2013, this was more of a locality than an indication of any monastery. A wooden bell tower was erected and the start of the restoration of this most severely damaged monastery on Fruška Gora was announced. Laying the foundation for the new monastery church and the monastery’s renovation began in September 2013. Thanks to contributions from benefactors, the church’s foundation was laid and a bell tower was built next to it with the original monastery bells. The cross was mounted on July 10, 2015.

We leave the wealthy monastery estate and return to the harsh “worldly” reality. Between the Bešenovo settlement and the village of Šuljam, there are a dozen buildings on the former state cattle farm. After the privatization, the property was abandoned and completely devastated. It resembles the abandoned city of Pripyat near Chernobyl. What remains are the empty cow feeders, an inscription “Privati posed” with a typo (an “n” is missing) and a more recent graffiti that reads “Comrade Tito”. “There used to be 300 cows there and half of the village population was employed on the farm. Following the privatization, everything was destroyed!” a resident of the village of Šuljam told us.

The story of Bešenovo – the village, the settlement, the monastery, the culture halls and the state farm is seen almost through the entire Srem District. Last autumn I visited the villages of Grgeteg and Krušedol. At the entrance to Grgeteg, right next to the creek, there is a memorial plaque dedicated to WWII fighters and victims of fascist terror who died between 1941 and 1945. This village is known for a rather infamous record – it has fewer inhabitants today than there are names on the memorial plaque.

According to the locals, 28 people live in Grgeteg today, and half of them left the village with the first signs of winter to spend the winter in Novi Sad or in one of the larger towns. So, there are 14 of them left in Grgetek throughout winter. While we are waiting for the official results of this year’s Population Census, we can only say that according to the 2011 Census, Grgeteg officially had a population of 76. The last child born in the village was in 1988. If nothing changes, there will be no residents here by the time the 2031 census comes.

Even though nature and history were very kind and generous to Grgetek, there is no store, school, doctor’s office or post office here. There are five guys in the village who are bachelors and there are no girls to get married to. They all have left the village for work and a better life. Grgeteg doesn’t even have a water supply system. Although a water grid was built a few years ago, water has trouble reaching the taps. Despite the promises made by the local government that they would resolve the problem, the locals are still struggling with drinking and technical water.

I attended regular Sunday services in several monasteries, where, like in the Rakovac Monastery a few weeks ago, there were no believers in attendance, except for priests and nuns

The Grgeteg Monastery lies at the very end of the village, which today has as many as 37 nuns, almost twice as many as the village’s population. I pass through the magnificent monastery gate and in the yard, I notice about twenty beehives. The hardworking nuns here make their own honey. The evening service is in progress. A nun kills the bugs that swarm around the floor at the front door. In the church, about twenty believers listened to the service in almost complete darkness, illuminated only by the light of candles.

A narrow paved road leads to the Krušedol settlement. The former Culture Hall is in the centre of the village. The small stage, where people used to perform back in the day, is covered in rubbish and there is graffiti all over the walls. One of them says: “I drink, therefore I exist!”. This is a sad situation that many villages in Vojvodina have found themselves in, where young people, mostly bachelors, are daily frequenting only three things – their home, a bar (if there is any) and a betting shop. In front of the former Culture Hall, there is again a monument erected in honour of WWII victims and next to it, between two linden trees, stretches a long bench, usually seating six or seven village seniors. On that day, on a sunny autumn Sunday afternoon, it was empty.

Below the Krušedol settlement, lies Krušedol Monastery, one of the most beautiful monasteries on Fruška Gora. In the monastery church, in the vestibule, rest the remains of many important Serbs, including Patriarch Arsenije III Čarnojević (1706), Metropolitan Isaija Djaković (1708), Patriarch Arsenije IV Jovanović Šakabenta (1748), Metropolitan Vikentije Popović (1725), Count Djordje Branković (here since 1744), colonel Atanasije Rašković (died in 1753), Duke Stevan Šupljikac (1848), Princess Ljubica Obrenović and King Milan Obrenović.

The same story goes for the Jazak Monastery, the surrounding hill and the village right next to it. The Jazak Monastery, built in 1736, suffered great damage during the Second World War. The then director of the Zagreb Museum of Arts and Crafts, Vladimir Tkalčić, took away with him 79 artefacts from the monastery. The partisans set it on fire in the summer of 1942 when part of the building burned down, the Germans took the wood from the remains, and an NDH (The Independent State of Croatia, translator’s note) official Anton Bauer took the rest of the valuable items from the monastery. Today, the monastery has been completely renovated – both the church itself and the lodgings. The Jazak settlement and the village of Jazak, which are next to the monastery, suffered the same destiny as Bešenovo, Grgeteg, Krušedol and many other villages in the Srem District. Every second house seems to be uninhabited, every third has either collapsed or is about to collapse.

How did it happen that Fruška Gora’s monasteries shine covered in gilded panels and freshly painted facades, while the villages in their shadow are decaying? In the past three decades, we have witnessed several processes that have led to this. The good condition of the Fruška Gora monasteries is thanks to the state authorities who started their restoration in the early 1990s when the controversial but agile Milan Paroški was at the head of the Provincial Institute for the Protection of Cultural Monuments. His mission was continued by Zoran Vapa, until recently the director of the same Institute, who is said to be the only official who came from the time of Slobodan Milošević and continued working in this position until the early 2020s, more precisely until 2021, when he retired. He was criticized by those members of the public who believed that the Fruška Gora monasteries were favoured over other cultural heritage in Vojvodina (castles, churches, fortresses, birthplaces of famous people…) which, if not restored with EU funds ( such as the Fortress and the Franciscan Monastery in Bač) or the Government of Hungary (synagogues in Subotica and Senta and numerous Roman Catholic and Protestant churches as well as historical buildings), is in a rather unenviable condition or has been demolished.

In the meantime, the Serbian Orthodox Church was given back a huge amount of property in restitution – from tens of thousands of square metres of apartments and houses in the centre of Novi Sad, Sremski Karlovci and other towns in Vojvodina to 4,479 hectares of forest in Srem, which is almost a fifth of the total area of the Fruška Gora National Park. Millions of euros are being poured into the coffers of the Srem Eparchy annually from renting and exploitation of forests, which has helped the Church to easily restore and maintain its monasteries and temples. If we add to that the generous donations of individual residents from these regions who live and work abroad, we get a picture of a very rich and privileged community. In addition, the Serbian Orthodox Church (SPC) and other religious communities were given huge tax reliefs, but also considerable autonomy in carrying out the preservation of cultural heritage in church property, which I wrote about in the article titled “War against Baroque” for Vreme weekly in 2020.

On the other hand, during the last three decades of transition, especially in the last 20 years, almost all culture halls in the villages of Srem were destroyed, as were many former agricultural cooperatives, local economies and agricultural combines. All those buildings are eerily empty today, graffiti-strewn, covered with rubble and trash on the floors, with severely cracked ceilings. The Secretariat for Culture of the Provincial Government of Vojvodina launched a special competition two years ago aimed at the renovation of cultural halls, however, it seems that this money was re-directed to bigger towns, leaving these villages, “which are empty anyway”, completely devoid of cultural content.

It seems that, on the one hand, Fruška Gora’s monasteries and the villages next to them, on the other, live in two completely different, parallel universes and that the class gap between the Church and the believers who live in the shadow of its bell towers is today the biggest since the Middle Ages

The villagers were further impoverished by the devastation of agricultural production, so most of the young people left, leaving only their elderly parents behind. In Pavlovci, a village in the Srem District, on the shores of its eponymous lake, many wealthy Belgrade residents built their mansions – from Andrija Drašković to Srdjan Djoković. The locals tell me that of the 120 cows that grazed the pastures here only ten years ago, today less than 20 remain. Private initiative in tourism exists with several wineries, craft breweries, guesthouses and restaurants operating in the vicinity, but this is still not enough to stop young people from leaving for cities.

The question here is if most of the locals have left and those who remain are mostly old and poor, who do so many churches serve? I attended regular Sunday services in several monasteries, where, like in the Rakovac Monastery a few weeks ago, there were no believers in attendance, except for priests and nuns.

However, the Fruška Gora monasteries have become a very fashionable and sought-after place for weddings and baptisms of members of the newly minted elite from Belgrade, Novi Sad and other larger cities. Of course, they are also visited by pilgrims and tourists coming to the area on river cruisers. In any case, it seems that, on the one hand, Fruška Gora’s monasteries and the villages next to them, on the other, live in two completely different, parallel universes and that the class gap between the Church and the believers who live in the shadow of its bell towers is today the biggest since the Middle Ages.