The demographic and architectural history of Bor, as well as the vision of its future, were also the inspiration for the work that will represent Serbia at the 17th Venice Architecture Biennale in 2021, which theme is “How will we live together?”, curated by Hashim Sarkis.

Sunčica Dimitrijević, Edvard Ernek, Xu Rui and Aneta Mirković Makulović are just some of the top nominees for the 2018 Best Individual Award, as featured on a large billboard put up by the Chinese company Zijin in front of the mine’s office building. Zijin acquired Mining and Smelting Basin Bor (RTB) in 2018. The names on the billboard speak of the dramatic demographic history of this mining place, which attracted the Czechs, Germans, Slovenes, Croats, Albanians, Belarusians and, as of three years ago, Chinese.

The demographic and architectural history of Bor, as well as the vision of its future, were also the inspiration for the work that will represent Serbia at the 17th Venice Architecture Biennale in 2021, which theme is “How will we live together?”, curated by Hashim Sarkis. The work of art titled “Eighth Kilometre: Survey Competition” was created by a group of authors – Iva Bekić (the group’s representative), Irena Gajić, Dalia Dukanac, Stefan Djordjević, Snežana Zlatković, Mirjana Ješić, Hristina Stojanović and Petar Cigić.

The exhibition commissioner Slobodan Jović, the authors Iva Bekić and Stefan Djordjević and I came to Bor last week to better understand the possibility for the national and international promotion of this fascinating project before the opening of the Venice Architecture Biennale on May 22.

I was working on my laptop in the back seat of the car and looked up when we were passing Donja Mutnica, after getting off the motorway near Paraćin. When we left Belgrade it was beautiful spring weather, yet when we arrived in this part of the country everything around us was covered in snow. Climate change and terrain configuration heralded future “surprises”. At the entrance to Bor, from the direction of Šarbanovci, on a pedestrian island between two roads, a huge mining truck called dumper, produced by the American manufacturer, Euclid, was parked. The dump truck has a load capacity of 170 and a net weight of 105 tonnes. People in Bor gave this exhibit a nickname – Gulliver – because its height and width exceed 12 metres, the tire diameter is 3 metres, while the fuel and oil tank can take 3,200 and 650 litres respectively.

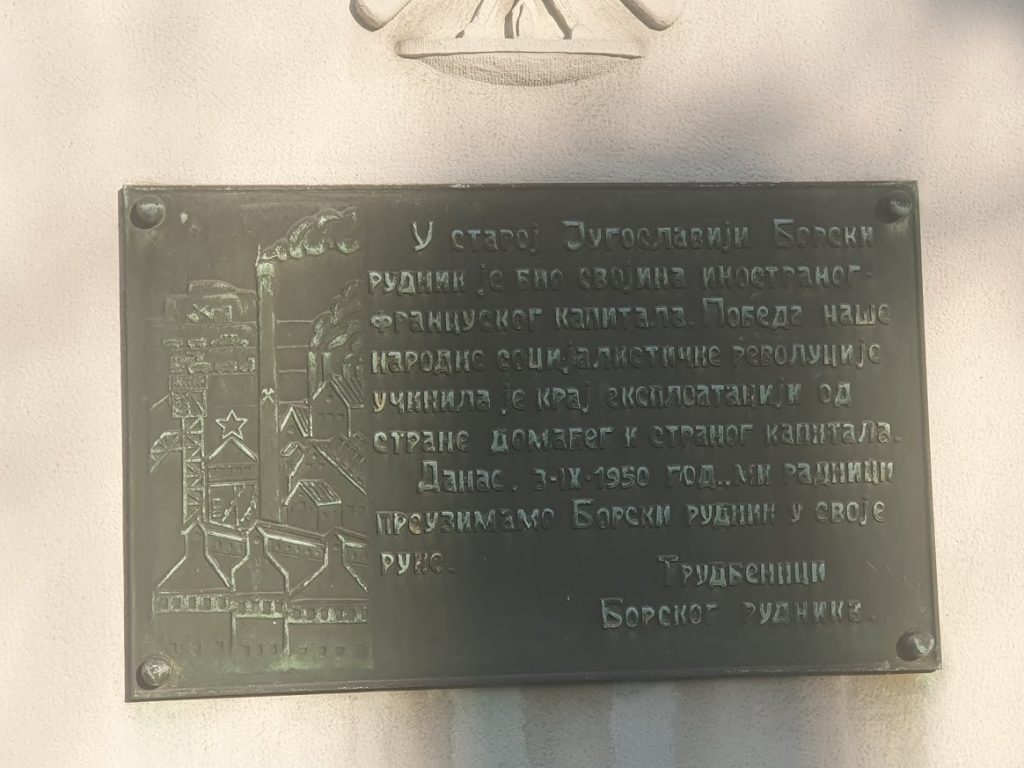

We arrive in front of the Mining and Metallurgy Museum in the centre of Bor. The Museum’s façade, built in the socialist realist style and also houses the National Library, bears the following inscription: “This building is dedicated to those people who gave their lives for the revolution.” Suzana Mijić from the Museum’s Ethnological Department shows us an anode cast made from Bor’s copper in 1961 by Josip Broz Tito, who, although visited the town only on three occasions, was and remains the favourite historical figure of the Bor locals.

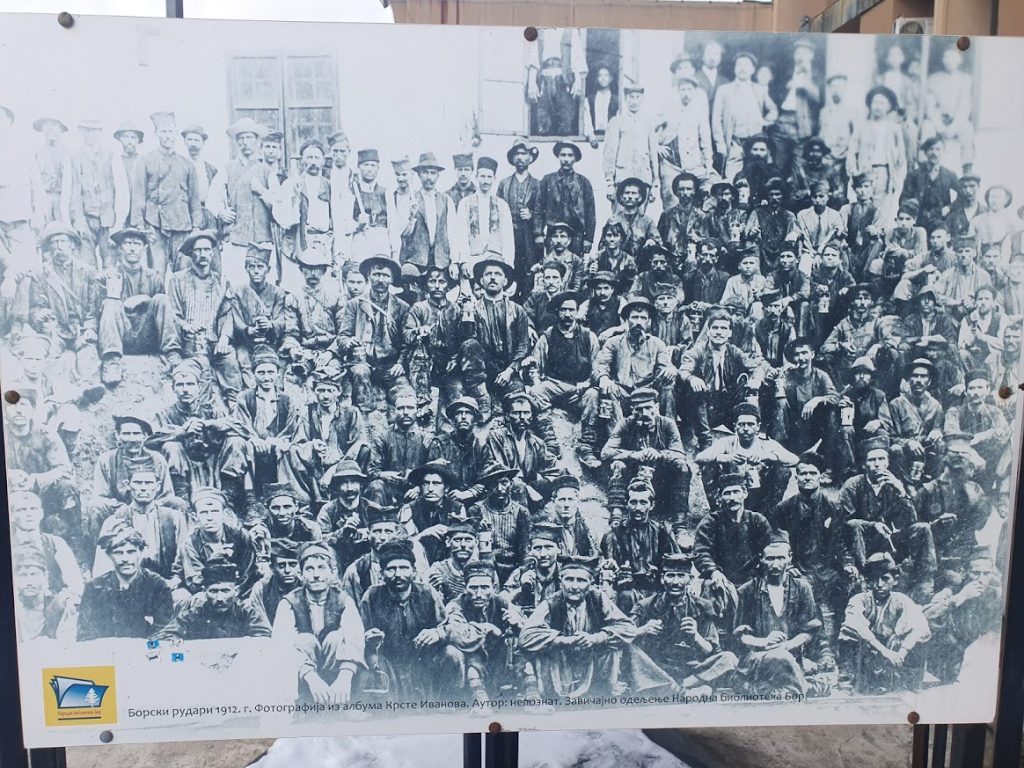

An exhibition of photographs from Bor’s history, which testifies not only to the history of the mine but also to the social life of miners, is staged in front of the Museum. Among the photos is the one depicting a race that took place in the 1950s with locals keenly watching a barefooted boy running through the town streets.

There is also a photo of the May Day celebration with a close-up of a father and son playing chess, closely observed by street hustlers.

Since the Museum is undergoing reconstruction, Suzana shows us the photos from an earlier exhibition in the part hidden by the screen. A small church that used to in Bor, but was later relocated, piques our interest.

The French Society of Bor Mines built a church dedicated to the Holy Martyr George in 1912 for the miners of Orthodox faith. It was smaller in size and due to the expansion of mining operations, it was relocated in 1937 to the village of Brestovac, not far from Bor. The new Orthodox Church of St. George in Bor was also built by the French Society of Bor Mines in 1939 and designed by Andrei Klepinin, a Russian emigrant. Representatives of the French Society of Bor Mines, i.e. its director, Emile Pialat, were the founders of this church.

Andrei Klepinin was not the only White Russian who found his happiness in Bor. Speaking through an anti-covid mask, Suzana tells us that many Russian emigrants came here between the two wars, most of them were older men who left behind their wives in Russia. They were not allowed to break the rules of their Orthodox faith, so they converted to Islam en masse so they could marry local girls.

ONLY ‘FERDINAND’ REMAINS

According to the last census from 2011, Vlachs make up 14% of the population of the town of Bor. There are also between 9 and 13 villages near Bor with a Vlach majority. The Vlach burial customs and their practice of black magic are widely known, but few people had the opportunity to see Vlach weddings which features “Govija Mika” (the Fake Bride), usually played by a ten-year-old girl.

If a census were to take place this year, it will show that the town, in addition to the nations listed at the beginning of the articles, is also home to hundreds of Chinese, if they are going to be included in the census at all.

Members of the Muslim faith in Bor have their own house of prayer, but they are not allowed to build minarets. Catholics gather in the Church of St. Ljudevit, which was built in 1928, and since most of the believers at that time were French, it is not surprising that the first priest was the French assumptionist, Privat Bellard.

After the Museum, we went for a walk around the town, wanting to get to the edge of the old surface mine. We pass a large empty billboard.

I cross the road to photograph the obituaries posted on a large board next to the monument to the victims of the 1912-1918 wars. A cursory glance gives the impression that the coronavirus epidemic took more lives in Bor than Turkish, Bulgarian and German bayonets and bullets combined.

The only billboard in the town that is not empty is located right above the Petković Mile Milan Law Firm. It’s partially torn but we can discern that it says “A Happy New Year and Merry Christmas 2021 from the Bor public enterprises and administration”.

Somewhat further down the road is the building that used to house the bankrupt Belgrade Department Stores, which is now divided into smaller shops. Across from it, on the dilapidated facade of a once beautiful modernist building, there is an inscription “Prenoćište Srbija”. The lights were turned off a long time ago in this “inn”, as the locals call it. From the main street named after Djordje Weifert, the initiator of mining in this area, we turn to the side, onto Djura Djaković Street, where the Zvezda cinema occupies the building from 1961.

In the deserted hall next to the museum exhibit of the old cinema projector, the only thing we can see is the advertisement for the cartoon “Ferdinand” which reminds us that films used to be screened here. One of my Facebook friends commented the following on the related post:” “After FEST, the Zvezda cinema in Bor was the next stop where the newest films were screened. We used to come from Zaječar, in the middle of the winter, to watch the best domestic and foreign movies.” Those days are long gone. I was slightly confused by the hum of the vacuum cleaner in the huge cinema hall (it has 622 seats and a screen measuring 16×7.5 metres). I asked the cleaning lady if the cinema is getting ready for re-opening. “Since October 23rd last year, when the state of emergency was declared in the municipality, no films or plays have been shown and staged here. We are now preparing this for the session of the Bor Assembly which is tomorrow.” It is held in this giant hall in line with the current epidemiological measures.

URBAN LEGENDS

Apart from billboards and plays, there is one more thing that people in Bor are missing – the traditional mining siren is no longer heard. It used to sound off five times a day for almost a century. It served as an ‘alarm clock’, going off at 06.00, followed by 06.45, then at 07.00 which announced the beginning of the first shift in the mine, followed by 15.00 one, marking the beginning of the second shift and the last, heralding the beginning of the third shift at 23.00. People from Bor set their clocks according to the siren throughout the 20th century, and after the bombing in 1999, the siren was silenced because it reminded locals of the unpleasant events that had just transpired. In 2009, this tradition was renewed following the initiative of the locals, but the Chinese, the new owners of the mine, stopped it again two years ago.

We pass by the new office building of the Zijin Company. I look at the names of awarded workers from the beginning of the story. We did not find out whether, in 2019, the first year after the Chinese acquired the mine, the rewards stopped, or the pandemic did its thing. We cannot help but notice that the entrance to the Zijin headquarters is modestly decorated, like a Chinese restaurant in Novi Beograd. Even more inconspicuous is the red-and-yellow paper sign with an inscription in Chinese, hung on the lavish gate of the old entrance to the F.D.B.R. (the French Society of Bor Mines) which was erected by the French.

We also come across dilapidated houses, each resembling the next, which the French built for miners (I saw similar ones in Beočin, built for cement workers, and in Vrdnik for local miners). A special type of house was built for single miners and was different to those for miners with families. I had the same impression I got in Beočin and Vrdnik – pre-war “capitalist exploiters” paid more attention to the stylistic and aesthetic moment of living of their workers than many modern tycoons cared about the aesthetics of their villas, worth millions of euro.

We come to the end of Djordje Weifert Street and to “the end of the world”. This is the abyss, or “the journey to the centre of the Earth”, as in the novel by Jules Verne or the song by Djordje Balašević. At the very edge of the abyss, there is mud covered with rubbish, and behind an old mine abandoned almost a decade ago with the mine floors and a tailings dump, there is a large hill created as a result of the exploitation of the Veliki Krivelj surface mine.

To the right of this unofficial lookout, where we cleaned our muddy shoes on the remaining piles of snow, there are buildings built by Zijin, surrounded by a high wall with barbed wire. In Zrenjanin, stories are circulating about how another Chinese company, Linglong, employs convicts to build its production plant in exchange for reduced sentences, with two of them sleeping in the same bed because their shifts last 12 hours. Similar “urban legends” are retold in Bor, but there is no official confirmation. As our hosts tell me, the locals generally live in peace with the Chinese because they are aware that despite all the objections they have, if it weren’t for them, the situation would be even worse and the mine would probably close.

CHRONICLE OF THE BOR CEMETERY

Next, we drive to Vidikovac, one of the biggest tourist attractions in Bor. There is no mud here. The road is made of stone gravel which leads to a large canopy surface from which you can see the huge abyss of the old mine, which is now largely filled with tailings.

It is interesting to note that in 2010, two domestic feature films were made which story takes place in Bor. Tilva Roš, the debut film of screenwriter and director Nikola Ležaić, won the best feature film award “Heart of Sarajevo” at the Sarajevo Film Festival that year. The film “Beli, Beli Svet”, directed by Oleg Novković and written by Milena Marković, was also shot in 2010. At the Locarno Film Festival, Jasna Djuričić won the Silver Leopard for the role of Ružica. I recommend watching both films to better understand the atmosphere of this mining town waiting for a new Truman Capote or Jo Nesbo to make it the central location in their books.

As we were leaving to go to the Ćira restaurant, where we will reflect on our impressions of Bor with plum brandy, aspic and roasted veal liver, I saw an old Orthodox cemetery and asked my companions to wait for me for a few minutes. I went down to the mounds, some of which look like ancient tombstones and are hundreds of years old. On average, every tenth grave is taken care of. It looks like abandoned German and Jewish cemeteries in Vojvodina, where members of the nations who had disappeared from this area are buried. But Serbs still live in Bor! Where are the descendants of these people? The answer to the question is written on the back of a headstone. I see a bunch of names, all members of one family: “Mirko 1939-2006 (France); Milinko 1940-1995 (the USA); Milosav 1942-2014; Mašan 1945-1999 (Belgrade), Milivoje 1948-20. .; Miodrag 1949-2015; Milica 1952-20…; Milan 1956-20… “

Mother gave birth to seven sons and one daughter. Those who died were buried somewhere far away – France, the USA, Belgrade… It is highly likely that the children and grandchildren of those who are still alive no longer live in Bor. If the census takes place this year, the statistics will certainly reflect what I saw in the Bor cemetery and on the town streets.

By Robert Čoban