Media Under Siege and a Society at a Crossroads

Interview by: Dragan Nikolić

Interview by: Dragan Nikolić

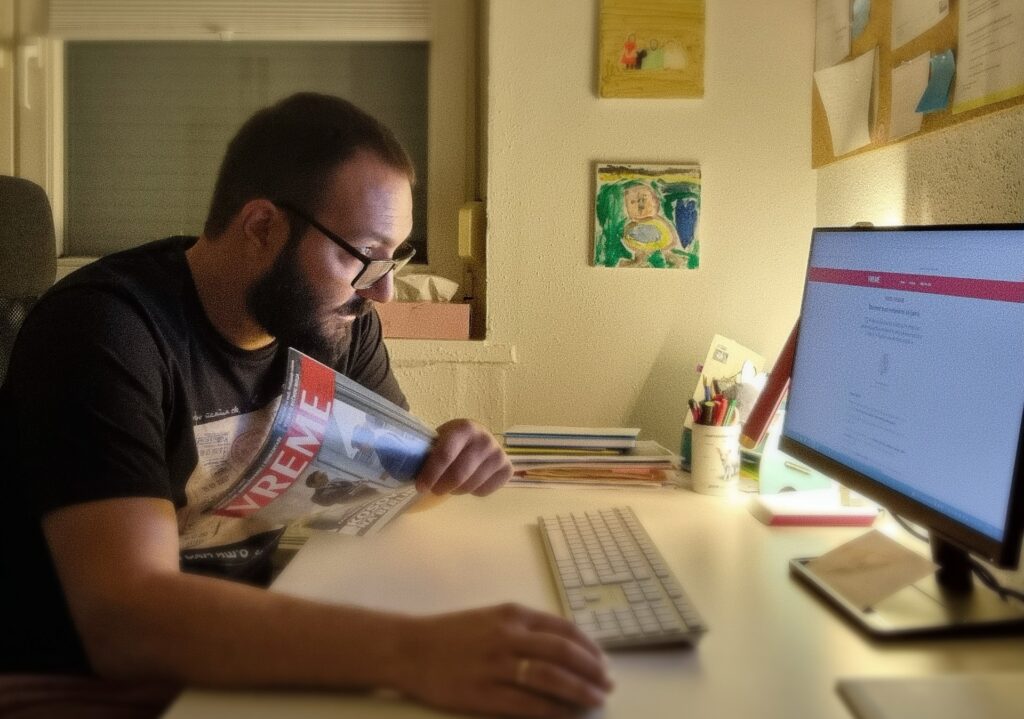

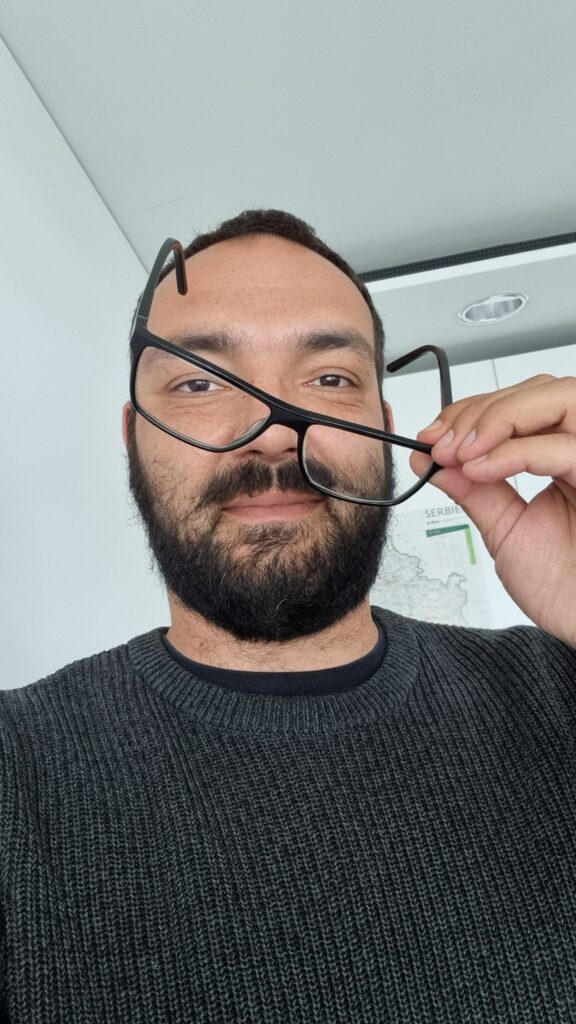

Journalist Nemanja Rujević dissects the state of media freedom, political control, and social unrest in Serbia. In this interview, he speaks about the tightening grip on independent journalism, the growing impact of student protests, and the West’s ambiguous stance on Serbia’s democratic struggles. With sharp insights and unfiltered opinions, Rujević questions whether real change is possible or the country is stuck in a cycle of repression and stagnation.

How Do You Assess the Current State of Media (Un)Freedom in Serbia?

Censorship is hardly even necessary anymore. By now, everyone knows what they can and cannot say. The President of Serbia acts as the chief editor of media outlets that control around 70 per cent of the market—indirectly, of course, through his media proxies, who have become enormously wealthy. Though, now and then, Vučić directly intervenes, even calling into TV programmes himself.

The remaining independent media have largely entrenched themselves in opposition, raising their defences against the regime’s attacks. However, this has also led to a certain complacency, where journalists hand the microphone to government critics who repeat the same things we have heard countless times. Of course, there are still excellent articles and investigative stories, but they rarely lead to any real consequences.

How Will the Sale of United Group’s Business Segments Impact the Media Landscape?

The deal is great for those who orchestrated this billion-euro transaction—they have never been too squeamish about working together when large sums of money are involved. But for the media landscape and the public, it is terrible news.

United Group invested in media outlets that criticised the government, providing a crucial counterbalance to the relentless propaganda of regime-controlled channels. If that disappears, Serbia will be left without major, financially strong media capable of delivering unfiltered criticism of those in power. What will remain is only carefully measured criticism on television, limited to whatever President Vučić deems acceptable.

That said, there are claims that N1 and Nova S will continue operating with the same editorial policy for years. Hopefully, that is true. A key indicator will be whether prominent journalists and editors start migrating to Telekom-owned television channels—where viewership is negligible. Still, salaries for top journalists rival those of airport directors.

Censorship is hardly even necessary anymore. By now, everyone knows what they can and cannot say

How Does Increased Political Control of the Media Affect Journalists in Serbia?

Not at all—nothing is easier. You decide not to sell yourself. They’re not executing people for it yet. Surviving in the media afterward is tough, but no one has starved. Stress, on the other hand, is another story.

What bothers me more is that the audience either doesn’t recognise what’s happening or, even worse, sees it and doesn’t care. In a media landscape where advertising money is cut off, state funds are funnelled through Telekom to regime tabloids, and journalistic ethics are optional, only the public can sustain independent media that report honestly.

But few people do. Hardly anyone buys newspapers, subscribes, or donates to independent media. People have grown used to everything being “free”, but it cannot be. If the audience refuses to pay, they will be informed by hobbyists or someone’s paid mouthpieces, not in the public interest, but in the interest of their financiers.

What Is the Social Significance of the Current Student Protests?

What Is the Social Significance of the Current Student Protests?

What is their central message, and how has the broader public received it?

Their significance is immeasurable. Someone said this isn’t a fight for freedom, but freedom has already arrived through the protest—above all, freedom from fear. As I mentioned, they’re not executing people yet. Young people have encouraged one another and emboldened entire cities, villages, professional groups, and even some unions.

Aside from its loyal enforcers who treat public tenders and job appointments as personal privileges, the regime is left with only the audience for Pink and Happy TV—those worn down by decades of this system, fearful that any change will mean lost pensions or party-controlled jobs.

The students’ message is simple—they want a functioning state. They don’t want to destroy it, as the regime and its cronies fantasise. On the contrary, they want the state to work as it should and can. It won’t become Norway overnight, but it can certainly be better.

This is where things get complicated. For students to get the state they are demanding—or as it is often put, “institutions”—the government must change. This regime is so deeply entrenched in corruption that it cannot allow functioning institutions to exist because that would mean doubling the capacity of Zabela prison and sending top officials to jail.

However, students do not explicitly call for a change in government, nor do they want to be associated with the opposition. This is understandable, given the opposition’s poor reputation after years of demonisation. But there is no alternative opposition. If students do not want to become one themselves, what do they want?

At some point, fatigue may lead student assemblies to declare their demands met, and they may return to their studies and exams. However, the demand for a proper state will not truly be fulfilled. This movement cannot go on indefinitely or repeat itself in endless cycles of protests without resolution. A possible outcome is pressure to form a transitional government and hold free elections. But for now, that idea is unappealing to the students.

Since it is unappealing to them, it is also unappealing to many citizens who say, “Lead the way, kids, you know best.” That may not be fair to the students, but they have become the only real political force standing against Vučić. And with that, they now bear the greatest responsibility.

How Do Western Countries View the Student Protests in Serbia?

People have been wrong all along when comparing Vučić’s era to Milošević’s, and they are even worse now. Milošević was largely “out of step” with the world, especially if we define the world as the West. Vučić, on the other hand, is entirely in sync with today’s global trends. Who is supposed to support change? Trump, Orbán, and Meloni? Or the Germans, too preoccupied with their troubles?

Beyond all other issues, the West and the European Union have long had a hypocritical approach to what they promote as “Western values.” These values apply at home but not necessarily elsewhere. Now, they are also facing an identity crisis—unsure whether those values even matter to them anymore, let alone whether they are willing to export them.

Vučić understands this game perfectly and knows exactly how to win people over. The key is to stay firmly in power, deliver just enough, and promise even more.

How Is the West, Especially Germany, Involved in Serbia’s Lithium Exploitation Plans?

It follows logically from the previous point. Germany’s auto industry is struggling, but it is the backbone of its economy. It has bet on lithium, and it needs it. Serbia has a world-class deposit, and it is unlikely that the German Chancellery will lose sleep over bats, farmland, rivers, or a farmer’s home in the Jadar Valley.

For a while, I thought Vučić saw this as his golden ticket in relations with Germany. Now, I’m not sure he will even dare to mention the project again anytime soon. Nor am I sure that Germany won’t find alternatives elsewhere. The resistance to mining in Serbia is too strong.

Either some unexpected event will collapse the regime like a flea market in a downpour, or this painful stagnation will drag on with an unpredictable outcome

Can Western Pressure Improve Media Freedom and Student Rights in Serbia?

I am not among those who believe in the “the worse, the better” strategy, hoping that someone will “sanction the regime.” We’ve seen around the world—and experienced firsthand—that sanctions always hurt the people. Ideally, the European Union would align with its contractual relationship with Serbia. Officially, that is what the EU accession process is about.

Specific standards must be met—some are ultra-capitalist, but most are not meaningless, particularly those related to the rule of law. The real issue is that Serbia is the only EU candidate with a serious obstacle in Chapter 35, which requires it to recognise Kosovo’s independence in some form. And you can’t have it both ways—if you want a strongman who “delivers” on Kosovo and other matters, there will be no rule of law or other democratic standards.

Even neighbouring countries without the Kosovo issue have struggled with EU integration. I’ve long believed that the accession process has been dead since Croatia joined—it’s just that everyone is pretending otherwise.

What Does the Future Hold for Media Freedom and Political Protests in Serbia?

What Does the Future Hold for Media Freedom and Political Protests in Serbia?

Things will likely have to get much worse before they get better. Either some unexpected event—a “black swan”—will cause the regime to collapse like a flea market in a downpour, or this painful stagnation will drag on, leading to who knows what kind of outcome. He wouldn’t be rigging elections if Vučić were willing to step down when the people demanded it.

Since even biology dictates that he must leave power one day, the real question is what the political and media landscape will look like when that happens. There will likely be a few years of confusion, shifting alliances, and a scramble for positions. But politics and the media will improve—so long as no one else accumulates the same power level as Vučić. That is what must be carefully watched.