Text: Žikica Milošević

Zoran Panović comes from an area ruled by down-to-earth sages and revolutionaries. His extensive knowledge of politics, social and sociological scene, makes Panović an apt commentator of today’s turbulent situation in Serbia, the region and Europe, which is on the crossroads.

Do you think that a pact, of sort, was created between the EU and stabilocracies such as Serbia and Montenegro where workers’ rights are not upheld, where there is very little freedom of information and where judicial independence is quite low, all in order to keep these countries on the pro-European path?

With its populist rhetoric, stabilocracy sounds attractive when talked about in the media, but, in sociological terms, stabilocratic regimes have authoritarian tendencies with one dominant political party or incomplete (destabilized) democracy. In Serbia, both the government and opposition are envious of the Montenegrin governance model. The pro-Western opposition in Serbia is envious of the Montenegrin political scene because of the determination and political power of Milo Djukanovic to fully incorporate Montenegro into the Euro-Atlantic structures. On the other hand, the Serbian authorities self-critically acknowledge their own occasional clumsiness in trying to implement the Montenegrin governance format in Serbia, since it is this format that is considered a role model in the region. In terms of democratic consolidation, stabilocracy brings a decline in the level of credibility of key institutions and stakeholders of representative democracy, while bolstering the influence of informal centres of power and limiting the development of civic culture. But, on the other hand, the European or Euro-Atlantic integrations in stabilocracies can be expedited, which is its main paradox. This is why Serbian President Vučić can be viewed through the unique model of euro-fanatical populist whose power technology, in all absurdity, can, at the same time, bring the country closer to the EU while tolerating the revisionist attitude towards the politics from the 1990s Serbia, which was euro-phobic. Cynics would say that that could be the only way for Serbia to join the EU. Let’s try to walk in the shoes of a Brussels pencil pusher who does not differentiate between the Balkan stabilocracy and democracy, but rather between stabilocracy and opposition in every of the little states in the region.

What is your opinion about media freedom under Milošević, Djindjić, Koštunica, Tadić and now? When was it the greatest and when the most limited? Whom do today’s politicians in power resemble the most in terms of media freedom and their ‘management’?

I am always going to quote the wise Vojislav Koštunica who said:“Media are either free or not“. It is as simple as that! If I had my choice, I would choose the state of media during Koštunica’s rule. In Milošević’s time, we had parallel worlds – the so-called regime media, which were warmongers and satanized the opposition, and the opposition fighters for democracy. Many people from the opposition today would like to go back to the 1990s, because in addition to revisionism, propagated by JUL and the Serbian Radical Party, there is this perverted civic nostalgia – the 1990s reeked, but at least it was warm then. We knew who we were and who they were and it was easier to function mentally in that dichotomy. Although the revisionist forces launched tabloids, and we are talking about those dark tabloids, the forces behind DOS (Democratic Opposition of Serbia) took over them, while Vučić absolutized them, thus bringing them into political mainstream. The tabloid consciousness and manipulation are the dominant state of mind today.

What can we expect from the Balkans in the future? A series of “ethnically defunct” feudal states that you can do whatever you want with, under the condition that they do not go against each other?

Do you remember when, about a year ago, an American security expert, John Schindler caused quite a stir after the New York-based newspaper The Observer quoted him saying that the West stopped insisting on preservation of internal borders of the failed Communist regimes in the Balkans? According to Schindler, the West should accept the mistakes it did in Southeastern Europe and rectify them before the Kremlin actually does. Schindler called Bosnia and Herzegovina a “decrepit pseudo-state” which must have gone down well with (Milorad) Dodik. The former CIA deputy chief for the Balkans, Steven Meyer made everybody’s eyes water here when he said (and was widely quoted) that, sooner or later, borders in the Balkans would change and ‘a Serbian union’ might even take place.

In late 2016, the renowned American magazine Foreign Affairs added fuel to the fire when they published an analysis of the political situation in ex-Yugoslavia, written by Timothy Less. In this piece, Less advocates border changes, and even a creation of Greater Serbia, Albania and Croatia, all for the sake of peace. Less goes on to say that the time has come for a new, more radical approach in order to preserve peace and promote stability in the Balkans. If the West, as Less claims, is really committed to preserving peace in the Balkans, then the time is right for pragmatism to trump over idealism and for the idea of properly regulated national states to come to fruition.

In this way, the Croatian ideal, which is for Serbs to finally become like Bulgarians to them as a prerequisite for peace, would come true. Because today, the friendship between Hristo Stoichkov and Miroslav Ilić, or the relations between the heads of the so-called Craiova Group (if that still exists), Aleksandar Vučić and Boyko Borisov are more important for the Serbian-Bulgarian relations than the historical events like battles of Slivnica or Bregalnica. Such annoying articles put Angela Merkel and the Berlin Process almost in the same group as historical events like AVNOJ, i.e. European humanitarian compensation for Tito’s charisma and his integrative mechanism of “fraternity and unity”. I can envisage anything but the ex-Yugoslav entities being able to find the mechanism of pacification of the conflict by themselves. Although Yugoslavia is long gone, the crisis will have the Yugoslav character for a considerable amount of time to come. The new narratives – those of the state – are, hence, a taboo and unchangeable. This revisionist tension will last as long as the current European constellation is alive. And if it collapses, God help us!

How powerless is the opposition today considering its malicious comments on social media and inefficiency in a sense that it lacks the energy and the ideas of the opposition from the 1990s?

The opposition is re-grouping, but there is still resistance to creating serious political parties. It still all boils down to initiatives and movements. It is tragic to see that now – almost three decades since the introduction of a multiparty system – our political stage is worse than in the 1990s. We do not have strong political parties in the opposition, and we need to build them from scratch. The opposition seems to be relying on ‘people self-organizing’. The wise Lenin said a long time ago that ‘there is no pure revolutionary situation.’ That is something that the opposition must accept. As for the media and institutions… Although it has electoral legitimacy, the SNS-led government perpetuates only one kind of revolutionism – the need to gather up everyone and to be in power in every single town and village. This is dangerous. We need a ’round table’ with the parties in power and in opposition sitting together. We need to lower the tension. The opposition wants the situation from the 1990s, but the present time is just like the 1990s, with the only difference being that the shops are not empty and we have international support. Consumer society goes against amassing opposition in the street; just like social networks spread cynicism instead of optimism. The message to Twitter users is a paraphrase of a popular graffiti: ‘Fishermen – grab the hoes!’ And applying the tactics of Jehovah’s Witnesses – going from door to door.

By joining the EU in 2013, Croatia has managed to become the poorest EU country in only five years. Does EU accession mean anything if a country is managed inadequately? What will our future be like? I mean the future in the Balkans, in Serbia. Migration and cheap labour?

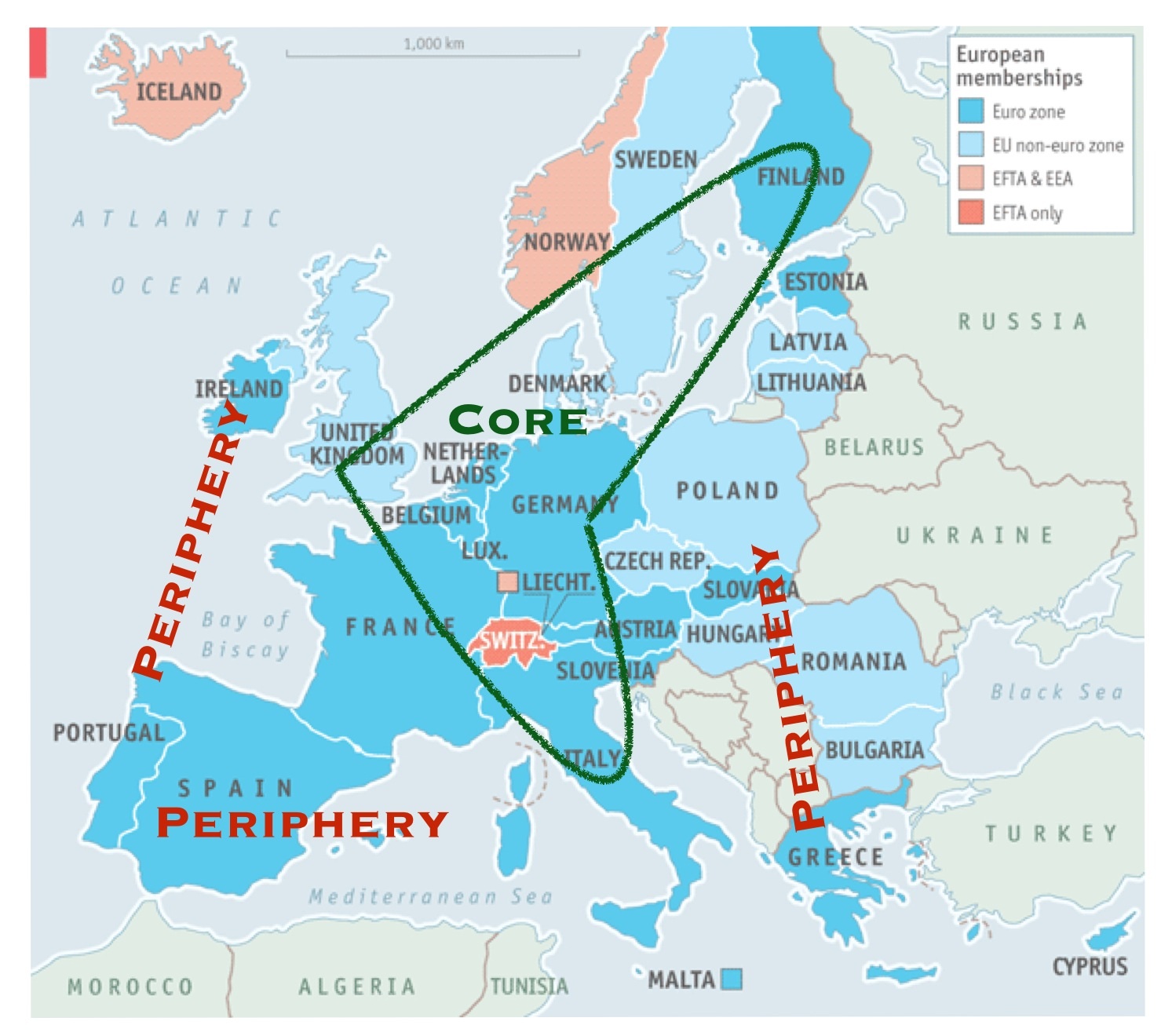

Hypertrophic identities from the 1990s wars and their continuation through use of peaceful means are incorporated into the Balkan narratives. This, unlike ideological conscience, is a fixed category. If you change or correct ideological conscience, you can be (or have been) both a revisionist and a heretic, but if you desecrate identity, you can only be a traitor. You have to read Amin Maalouf. Using a harmless question that he is often asked, this French academic explores the notion of identity, the passions that identity arouses and the deadly consequences. As The Guardian once wrote, Maalouf’s book “Murderous Identities“ are “a voice that we cannot afford to ignore.” This is a book of wisdom and lucidity. We can use Dragan Marković Palma’s patriotims quote for for the narratives too – patriotism will not provide fuel for tractors. That’s why people are leaving Slavonija, for instance. If we all get to join the EU, then the narratives will lose power. Every EU country has a little bit of Austro-Hungarian Empire and a little bit of Yugoslavia in them. This is more important to us than the economy. This region will become a part of the capitalist semi-suburbs, even if we all join the EU.

Do you think that the referendum on border demarcation, which entails a seat in the UN for independent Kosovo, would be heralded as a victory against the Greater Albania for Vučić and Serbia, or is it just a farce that people will grasp sometime in the future?

It is hardly likely that the referendum question would go against Vučić and sound something like – „Do you agree that we should declare Kosovo an occupied territory?“. Or maybe, after the referendum, Vučić will pull a ‘Tsipras’. Remember when the Greeks said „no“ to the demands of creditors at the referendum and Tsipras, once again, demonstrated his Machiavellian skills? The biggest danger lies in the referendum question being manipulative in nature, instead of it being a final clarifier since Kosovo is the hotspot of hypocrisy. In terms of political marketing, Vučić will try to portray something that was imposed as a victory and as Serbia entering a new era. This is very plausible scenario because the propaganda machine of this burnt-out country works in such way that even Angela Merkel could share the same destinty as Rada Trajković. The only thing that is important is for Trump to lean a little bit towards our side and that Putin has its own interests in the demarcation.